![]()

Chapter 1

Physical Integration: Separate Is Not Equal

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

There's a verse in Bob Dylan's 1964 song "My Back Pages" that provided us with both confidence and a caution as we embarked on our school equity work:

A self-ordained professor's tongue

Too serious to fool

Spouted out that liberty

Is just equality in school

"Equality," I spoke the word

As if a wedding vow

Ah, but I was so much older then

I'm younger than that now

Dylan recognized that in the midst of the great civil rights awakenings of the 1960s, public education continued to be a hallmark of this country's commitment to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. We can find a record of the hopes and expectations bound up in U.S. public education in letters exchanged by Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe. In these letters, each asserted the need and commitment to educate every citizen and expressed the belief that, as Jefferson (1787) wrote, education provides "the most security for the preservation of a due degree of liberty."

Like the protagonist of "My Back Pages," we have come to see the naiveté of assuming that the relationship between school equality and liberty is a simple or a linear one. Since Dylan wrote this song in the mid-1960s, there have been many policy-driven changes in public schools that have made them more equal, and yet widespread inequity persists. The words of the singer—wiser now, having shaking off the received truth of "self-ordained professors"—capture what we ourselves have come to believe through our work in schools: that a faithful focus on equality is not enough to promote liberty and justice for all. Equality is rooted in the concept of fairness, and a fair race is impossible when its various runners start at variable distances from the finish line, and the course takes them over very different terrains. Similarly, providing equal access to the stairway does not promote fairness to those who use wheelchairs. Achieving equity requires that this fact be acknowledged—and that we build a ramp alongside every stairway.

Without doubt, there are many groups that have been historically marginalized by both private sentiment and public policy. This deep-rooted marginalization is why both equality and equity remain critical concerns for public institutions, including our schools. Resources are not distributed equally among our schools, and some of the students who enter them are less prepared to benefit from the resources that are available. It's important to pause for a moment and considered how these concerns are intertwined. Advocating for advanced teacher education to support English learners (which is an equity-related resource that can help level the playing field) in a district's lowest-achieving school with its highest percentage of English learners may not address the underlying issue of low student achievement when the school is staffed with the district's least-experienced or least-qualified teachers (which reflects unequal distribution of resources).

Taking Integration from Equality to Equity

Despite the framers of the Constitution's assertion that public schools were to be both the fuel and model of democracy, racial inequities have permeated and persisted in business, social, and governmental structures. There has been a pervasive movement to provide equal and equitable access to public education, fueled by a landmark Supreme Court ruling declaring that the doctrine of separate but equal had no place in public schools. This was followed by the Court's rulings requiring school districts to desegregate with deliberate speed. Thwarting these progressive efforts were 70 years of Jim Crow laws, pushbacks to forced and often poorly supported busing programs, and housing patterns that have maintained and increased the number of racially segregated neighborhoods. Whether it is a result of pervasive racism, poorly conceived public policy initiatives, or the effect of poverty and housing trends on school placements, the fact remains that the number of minority-majority schools is increasing, and that distinction continues to be a key indicator of educational performance. Despite notable exceptions, the more "separate" students are, the more unequal their outcomes remain. This is why physical integration is the foundational tier in the Building Equity Taxonomy.

Most of the policies and practices capable of rectifying aspects of inequity are beyond the purview of building-level decisions and, therefore, beyond the purview of this book. However, we must be aware that efforts to create more equitable learning environments will be limited by the extent to which schools remain segregated based on race, socioeconomics, and ability. These inequities must be addressed through progressive and institutional urban development, housing and educational policy initiatives, and structural changes designed to cope with the present-day effects of a long history of exclusion and segregation. We must remember, too, that the real goal to work toward is success for every student—and simply getting students in an integrated setting is insufficient to change the outcomes for many students. To truly level the playing field, educators must move beyond a focus on equality and start demanding equity. By focusing on equity, we expand our efforts beyond student placement. And in doing so, we can broaden our vision to include not only equity for students of all races and ethnicities but also for students of all socioeconomic statuses; degrees of language proficiency; gender identities; sexual orientations; and physical, emotional, behavioral, and intellectual abilities.

Broadening the Equity Lens: From Race to Identity

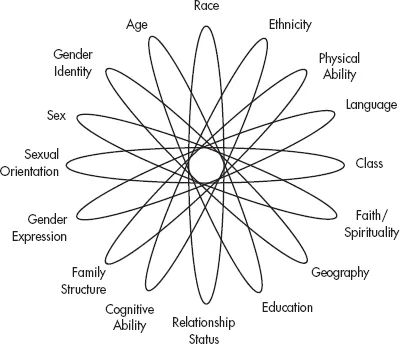

Over time, the recognition that separate schools could not be equal schools codified in Brown vs. Board of Education has evolved from a single-issue focus on race to conversations that include ethnicity, language, gender, sexual orientation, and disability. Whereas integration in U.S. public school was once primary about racially balancing a school's population of African American and white children, more recent explorations of identity have complicated the metrics of integration. First, we moved to consider an expanded number of racial and ethnic identities—Asian American, Latino, white, and Native American students as well as African Americans. Next, we opened our eyes to the numbers of low-income students, English language learners (ELLs), and students with disabilities. Now, we're factoring in intersectionality (e.g., Crenshaw, 1989; Jones & McEwen, 2000) and recognizing that our students are more than just a single racial, ethnic, or ability group assignment—that they have layered lives and affiliate with others through a complex mix that includes not only the aforementioned identities and the societal lens applied to each but also religion, geography, family relationship status, and age (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Dimensions of Identity

Source: Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, DHS LGBTQ Community Training Team/SOGIE Project Team. Reprinted with permission.

To provide just one illustration, a 9-year-old girl with Pacific Islander heritage living in Springdale, Arkansas (home to the largest expatriate population of Marshall Islanders in the world), is likely to experience schooling differently than a 9-year-old girl living in a community where hers is the only Pacific Islander family. The experience of this student would shift in all sorts of ways if her family were the wealthiest in the community or the poorest, if she were transgender, if she were gifted or had an intellectual or emotional disability, and on and on. Educators' efforts to improve the learning lives of all children must consider how dimensions of identity beyond traditional demographic measures can inform how we address social-emotional engagement, create more robust opportunities to learn, strengthen instructional excellence, and empower students.

Expanding the Interventions: From the Classroom to the Whole School

Ensuring equitable educational opportunities is a concern at both the school and district levels. Certainly there will be a need for targeted interventions, but creating a culture of achievement is an issue that touches the lives of all students, albeit in different ways. By broadening single-focus equity initiatives to comprehensive, schoolwide measures and approaches, we can make the practices that support equity standard practice.

Although the outward expression of inequitable practices may differ by group—for example, gender inequities look substantially different from limited opportunities to learn for black and Hispanic/Latino students living in poverty—each serves as a litmus test of a school's or district's responsiveness to the biases that its students experience. We can't move forward in discussing social-emotional engagement, opportunities to learn, instructional excellence, and student engagement and inspiration without first examining whom our efforts might affect.

Building Equity Review Statements: Physical Integration

It's time to delve into a discussion of the first group of statements in the Building Equity Review. These statements—and the examples we share of how teachers, administrators, and students we have worked with have responded to these statements—are meant to provoke conversation and kick off your equity work. Ultimately, we hope they will inspire your school to engage in the full Building Equity Audit and take targeted action.

As you review the set of statements associated with Level 1 of the Building Equity Taxonomy, keep in mind that physical integration is a necessary but singularly insufficient response to the equity crisis. Said another way, students have to be present in a valued learning environment, and we have to address their social-emotional engagement and their opportunities to learn. We have to ensure instructional excellence, and we have to give students voice while honoring their aspirations. To our thinking, this work starts with getting students in an integrated educational setting.

1. Our student body is diverse.

This statement asks teachers to consider what a diverse student body really is, with the reminder that that the definition of diversity should not be limited to a student body's racial, ethnic, or cultural composition. Ideally, a school should represent the diversity that exists in society. What complicates this ideal is that the immediate community and neighborhoods may not represent the diversity of society at large, and this is something the stakeholders in a school should bear in mind by considering who is represented and underrepresented. Knowing this is empowering, as it casts a light on who may be left vulnerable or isolated. Further, it affects the ways in which a school can address issues of fairness, privilege, and need. Awareness of diversity can generate ideas for supports, services, curriculum, and projects, and these ideas can find their way into equity plans that are generated throughout each tier of the Building Equity Taxonomy.

Sometimes physical integration is just a matter of an invitation. Members of the staff of Heritage Elementary School noticed that there were several neighborhood children who were being bused to another school that had a specialized class for students with significant disabilities. They talked with their principal about this, and she crafted a letter to these children's parents and guardians inviting them to consider enrolling their child at Heritage. As part of her letter, the principal wrote, "You may be asking yourself why our school decided to reach out to you. Simply said, our current students are missing the opportunity to learn from, and with, your child. There is a wide range of human experience that our current students are missing—and part of that is because your child is not in attendance here." Of the seven students whose families received the letter, four were enrolled immediately. The school asked for and received district-level support in terms of staff and professional learning, and the principal said that she was thrilled with the outcomes. The parents of the students with significant disabilities reported increases in their children's social skills, friendships, and academic performance, and there was widespread agreement among the Heritage stakeholders that this step toward increased integration enriched the learning experience for all.

2. Our school publicly seeks and values a diverse student body.

Regardless of the current demographics of your school, this statement prompts you to analyze the environment for evidence that educating a diverse group of students is important to the people who work there. There are any number of ways that a school can demonstrate its values, including inviting students who do not currently attend to join the campus, as the principal of Heritage did. Further, when staff members step up to point out that their school does not represent the diversity found in the community and advocate for change, it sends a clear message that all students are welcome.

The staff at Valley View Elementary School post signs around the school in Korean, even though they have only a few enrolled students who speak the language. As one of the teachers noted, "Language and culture are interconnected. When people see their language, they feel more comfortable. It's like we're saying, "We value you here." The teachers know that there are many more Korean-speaking students in an adjacent community, and they want everyone to know that they are welcome. The parents notice. One was overheard saying, "They take the time here to make you feel important. All of the directions and signs are in Korean, not just English and Spanish. I've told my friends that they should think about coming to this school." Valley View staff are quick to point out that this isn't about enrollment competition but about clarifying to the community that every child matters.

The signs in Korean are just one way that the staff at Valley View have publicly expressed their support for educating a diverse group of students. They also recognize that a significant percentage of their students live in poverty, and they have taken steps to show these students and their families that they are important in the school community. As one outward expression of this, Valley View installed washing machines and dryers in a former staff room so that parents could clean their children's clothes at no cost (a small community grant covers the expense). While the clothes are being washed, parents are invited to attend language development classes or financial literacy seminars or to volunteer in the classrooms.

Sometimes, staff education is a necessary precursor to publicly valuing a diverse student body. When Kennedy Middle School first began seeing female Muslim students wearing the hijab, or traditional headscarf, several staff members went to the administration with concerns. As one of the teachers wondered, "If Rabab can wear the hijab, what other things will students want to wear? I can just see my boundary-pushing kids saying they want to wear ski masks or pajamas all day. Does this mean our dress code will go right out the door? It clearly says that there are no caps, hats, or bandanas allowed."

Understanding that there was both a lack of information and a bit of fear behind such remarks, two history teachers invited a local Islamic religious leader to the school—setting up a completely voluntary after-school informational session for all staff. Attendees were urged to ask questions and to learn more about the traditions valued by Muslims. The teacher who made the comment about her student Rabab said afterward, "I had no idea that wearing the hijab was a custom, like wearing the cross is for me. It's not some random thing; it's part of a religious tradition. I feel bad for suggesting that it was just in defiance of our dress code."

The Valley View staff decided that they needed to update the dress code, which they did. But even more important, they decided to update their promotional materials to feature photographs of Muslim students wearing the hijab. They also scheduled a series of public seminars for the community and assemblies for students to facilitate their understanding of Islamic traditions. This last action generated some pushback from other religious communities, and the staff decided to host an annual Day of Understanding that would allow people to learn about cultures and traditions present in the community that are different from their own. The staff also invited religious leaders to attend the student-focused events and changed the emphasis from Islamic traditions to comparative religion.

3. Efforts are made to promote students' respecting, and interacting with, students from different backgrounds.

The whole idea of integration is for diverse groups of students to interact with one another. Unfortunately, in a lot of integrated schools, students form groups in which membership is defined by ethnicity, language, gender, or some other demographic.

The staff at Red Canyon Middle School noticed that parts of their school were highly segregated, despite the fact that their school represented the larger community well and was demographically very diverse. A look into the lunchroom highlighted this fact. In one area, all of the students were black. In another area, all of the students were Latino. Students did not interact across racial/ethnic lines during lunch or, the staff also noted, on sports teams or at social events such as dances.

When this student self-segregation was brought up during a faculty meeti...