![]()

Chapter 1

Learning and the Intentional Act of Teaching

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

As many have noted, teaching is both an art and a science. On the "science" side, there is considerable evidence about the measures proven to support learning that educators can use to inform instructional decisions. We ignore that evidence to our, and our students', peril. Aspects of teaching that fall under the "art" heading include healthy teacher–student relationships, the classroom learning climate, and teachers' passion for the work and their students' learning. This book focuses more on the science of teaching than the art, but you'll read examples that clearly mobilize both art and science.

What's most important is that teaching lead to learning—that it develop in students the knowledge, skill, and confidence they need to learn deeply, think critically and creatively, and be able to apply learning strategies to meet new challenges. If what we are doing is not having that effect, we need to change what we are doing.

The Case for Instructional Frameworks

There is a difference between being prescriptive about instruction and being intentional about it. The purpose of instructional frameworks is not to undercut teacher expertise or professionalism or to tell teachers what to say and how to say it; it's to provide a system of expectations for how students might be taught. Instructional frameworks are a tool that teachers can use to design learning and make informed decisions about the specific strategies that will best support their students' success. In addition, instructional frameworks create a shared vocabulary so that members of teacher teams can communicate more effectively when they interact with one another. Instructional frameworks make it easier to discuss instruction across platforms (face-to-face, distance learning, blended, or hybrid variants). Further, they help teachers identify professional learning opportunities. For example, if one aspect of an instructional framework focuses on student-to-student interaction, teachers might want to learn new ways to enhance this in their classrooms.

Essentially, an instructional framework is a way to organize strategies and deploy them to create cohesive learning experiences for students. It's a defense against the all-too-common and frankly exhausting "buffet model" of professional learning, where teachers are prompted to keep adding to their plates without any idea of where they're going to "put" it all.

A number of instructional frameworks have been developed over the years, but the one we'll be focusing on is called the gradual release of responsibility.

The Gradual Release of Responsibility: A Structure for Supporting Learning

The gradual release of responsibility instructional framework is based on the belief that teachers can intentionally increase students' ownership of learning over time. The framework is informed by several complementary theories, including the following:

- Piaget's (1952) work on cognitive structures and schemata

- Vygotsky's (1962, 1978) work on zones of proximal development

- Bandura's (1965, 2006) work on attention, efficacy, retention, reproduction, and motivation

- Wood, Bruner, and Ross's (1976) work on scaffolded instruction

Taken together, these theories suggest that learning occurs through interactions with others, and being intentional in these interactions allows for specific learning to occur. The mechanism behind the gradual release of responsibility is purposefully shifting the cognitive load from teacher-as-model to joint responsibility of teacher and learner, and then to independent practice and application by the learner (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983). This gradual decrease of teacher responsibility and parallel increase in student responsibility may occur over a single lesson, a day, a week, a month, or a year.

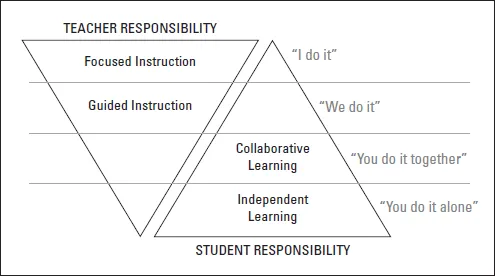

In the past, interpretations of the gradual release of responsibility limited these interactions to adult and student exchanges: I do it; We do it together; You do it. But that three-part model omits a truly vital component of learning: students' collaboration with their peers—the You do it together phase. Thus, our interpretation of the gradual release of responsibility framework includes four major phases. In Figure 1.1, we map out these phases of learning, indicating the share of responsibility that students and teachers have in each.

Figure 1.1. A Structure for Instruction That Works

We are not suggesting that every lesson must always start with focused instruction (goal setting and modeling) before progressing to guided instruction, then to collaborative learning, and finally to independent tasks. Teachers can and often do reorder the phases—for example, beginning a lesson with an independent task, such as bell work or a quick-write, or engaging students in collaborative peer inquiry prior to providing teacher modeling. As we stress throughout this book, what is important and necessary for deep learning is that students experience all four phases of learning when encountering new content. We will explore the four phases in greater detail in subsequent chapters, but let's proceed now with an overview of each.

Focused Instruction

This phase includes two components: establishing the purpose for learning—that is, setting learning intentions and success criteria—and providing cognitive apprenticeship opportunities through modeling and demonstration. In focused instruction (which, as noted, does not have to come at the beginning of a lesson), students get to know what they are learning and see examples of the type of thinking that they are expected to do. Here are some examples of what teachers and learners might be doing during the focused instruction phase:

Teacher Actions

- Describing the learning intentions and success criteria

- Noting the relevance of the lesson

- Thinking aloud, demonstrating, or providing direct instruction

Student Actions

- Listening and making connections

- Taking notes or talking with a partner about what the class is learning

- Developing a mental model of expertise

Focused instruction is typically done with the whole class and usually lasts 15 minutes or less—long enough to clearly establish purpose and ensure that students have a model from which to work. Bear in mind, too, that there is no reason to limit focused instruction to once per lesson. The gradual release of responsibility instructional framework is recursive, and a teacher might reassume responsibility several times during a lesson to reestablish the lesson purpose and provide additional examples of expert thinking.

Guided Instruction

The guided instruction phase is an opportunity to scaffold students' understanding. Through the use of questions, prompts, and cues, teachers can support student learning without telling them answers or simply providing them with information. Guided instruction can be done with a whole class, but many teachers are more effective when they guide small, purposeful groups that have been composed based on assessment data. Here are some examples of what teachers and learners might be doing during the guided instruction phase:

Teacher Actions

- Asking questions

- Scaffolding with prompts, cues, and direct explanations

- Meeting with intentionally selected groups of students

- Monitoring progress and documenting learning

Student Actions

- Responding to the teacher's questions

- Thinking and noticing, based on the scaffolds

- Experiencing productive success with the support of the teacher

Guided instruction is an ideal time to differentiate learning experiences by varying the instructional materials used, the level of prompting or questioning employed, and the products expected. A single guided instructional event won't translate into all students developing the content knowledge or skills they are lacking, but a series of guided instructional events can. Over time and with cues, prompts, and questions, teachers can guide students to increasingly complex thinking. Guided instruction is, in part, about establishing high expectations and providing students with the support they need to reach those expectations.

Collaborative Learning

The collaborative learning phase of instruction is too often neglected. If used at all, it tends to be a "special event" rather than an established instructional routine. When done right, collaborative learning is a way for students to consolidate their thinking and expand their understanding. Negotiating with peers, discussing ideas and information, problem solving, and engaging in inquiry with others give students the opportunity to use what they have learned during focused and guided instruction. Here are some examples of what teachers and learners might be doing during the collaborative learning phase:

Teacher Actions

- Developing complex tasks

- Forming groups purposefully

- Assigning roles

- Monitoring progress

Student Actions

- Using academic language in interactions with peers

- Sharing opinions, ideas, and thoughts

- Problem solving and using argumentation

- Working to achieve consensus

Because collaborative learning situations help students think through key ideas, they are a natural opportunity for inquiry and a way to promote engagement with the content. As such, they are critical to the successful implementation of the gradual release of responsibility instructional framework. Note, though, that collaborative learning is not the time to introduce new information to students. This phase of instruction is a time for students to apply what they already know in novel situations or engage in a spiral review of previous knowledge.

Independent Learning

The ultimate goal of instruction is that students be able to independently apply information, ideas, content, skills, and strategies in unique situations. We want to create learners who are not reliant on others for information and ideas. As such, students need practice completing independent tasks and learning from those tasks. Overall and across time, the school and instructional events must be "organized to encourage and support a continued, increasingly mature and comprehensive acceptance of responsibilities for one's own learning" (Kesten, 1987, p. 15). The effectiveness of independent learning, however, depends on students' readiness to engage in it; too many students are asked to complete independent tasks without having received the focused or guided instruction they need to do so successfully. Here are some examples of what teachers and learners might be doing during the independent learning phase:

Teacher Actions

- Developing practice and application tasks

- Monitoring student progress

Student Actions

- Completing assignments

- Planning and monitoring their own efforts

- Reflecting on their own successes

When students are ready to apply skills and knowledge, there is a range of independent tasks that might be used. Our experience suggests that the more authentic a task is, the more likely the student is to complete it. For example, a kindergarten teacher might ask a student to read a familiar book to three adults, a 6th grade science teacher might ask a student to predict the outcome of a lab based on the previous three experiments, and a high school art teacher might ask a student to incorporate light and perspective into a new painting. What's essential for an independent learning task is that it clearly relate to the instruction each student has received yet also provide the student an opportunity to apply the resulting knowledge in a new way.

Structures That Don't Support Learning

With this effective approach to instruction fresh in mind, let's look at some structures that don't support learning nearly as well. Unfortunately, there are still plenty of classrooms in which responsibility for learning is not being transferred from knowledgeable others (teachers, peers, parents) to students. Although they may feature some of the phases of instruction we have described, the omission of other phases derails learning in significant ways.

For example, in some classrooms, teachers provide explanations and then skip straight to asking students to complete independent tasks—an approach graphically represented in Figure 1.2. This situation is very familiar. A teacher demonstrates how to approach a particular kind of algebra problem and then asks students to solve the odd-numbered problems in the back of the book. A teacher reads a text aloud and then asks students to complete a comprehension worksheet based on the reading. In both cases, the teacher fails to develop students' unde...