![]()

Chapter 1

Supervision That Develops Expertise

Supervision has been a central feature on the landscape of K–12 education almost from the outset of schooling in this country. Witness the following comments from a 1709 document entitled "Reports of the Record of Commissions of the City of Boston" (cited in Burke & Krey, 2005, p. 411):

[It should] be therefore established a committee of inspectors to visit ye School from time to time, when as oft as they shall see fit, to Enform themselves of the methods used in teacher of ye Scholars and Inquire of their proficiency, and be present at the performance of some of their Exercises.

In the three centuries that have transpired since this proclamation of 1709, the world of K–12 education has changed dramatically. Along with changes in curriculum, instruction, and assessment have come changes in perspectives on supervision and evaluation. In Chapter 2, we briefly trace these changes to provide a frame of reference for the recommendations made in this book. Throughout the remainder of the book, we lay out a comprehensive approach to supervision as well as address the implications of our approach for the practice of evaluation.

The Foundational Principle of Supervision

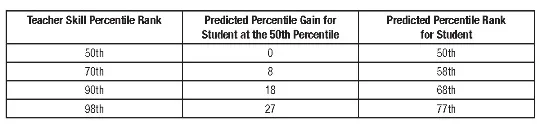

The recommendations in this book are grounded in one primary principle that we view as foundational to the evolution of supervision: the purpose of supervision should be the enhancement of teachers' pedagogical skills, with the ultimate goal of enhancing student achievement. Even a brief examination of the research attests to the logic underlying this principle. Specifically, one incontestable fact in the research on schooling is that student achievement in classes with highly skilled teachers is better than student achievement in classes with less skilled teachers. To determine just how much better, consider Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Teacher Expertise and Student Achievement

Figure 1.1 depicts the expected percentile gain in achievement for a student starting at the 50th percentile within classrooms taught by teachers of varying degrees of competence. A student at the 50th percentile will not be expected to gain at all in percentile rank in the classroom of a teacher of the 50th percentile in terms of his or her pedagogical skill. However, a student at the 50th percentile will be expected to advance to the 58th percentile in the class of a teacher at the 70th percentile in terms of pedagogical skill. The increase in student percentile rank is even larger in the classrooms of teachers at the 90th and 98th percentile ranks in terms of their pedagogical skill. Students in these situations would be expected to reach the 68th and 77th percentiles, respectively. Clearly, the more skilled the teacher, the greater the predicted increase in student achievement. Equally clear is the implication for supervision. Its primary purpose should be the enhancement of teacher expertise.

Although it is unreasonable to expect all teachers to reach the lofty status of the 90th percentile or higher regarding their pedagogical skills, it is reasonable to expect all teachers to increase their expertise from year to year. Even a modest increase would yield impressive results. Specifically, if a teacher at the 50th percentile in terms of his or her pedagogical skill raised his or her competence by two percentile points each year, the average achievement of his or her students would be expected to increase by eight percentile points over a 10-year period.

We believe that when done well, the process of supervision can be instrumental in producing incremental gains in teacher expertise, which can produce incremental gains in student achievement. Additionally, we believe that the research provides rather clear guidance on how to enhance teacher expertise.

The Nature of Expertise

Relatively speaking, it was not that long ago that expertise was considered something that could not be developed. Rather, expertise was thought of as a natural by-product of talent. In his review of the historical literature on perceptions of expertise, Murray (1989) concluded that it was generally believed that talent was considered "a gift from the gods." About this notion, Ericsson and Charness (1994) note:

One important reason for this bias in attribution … is linked to immediate legitimization of various activities associated with the gifts. If the gods have bestowed a child with a special gift in a given art form, who would dare to oppose its development, and who would not facilitate its expression so everyone could enjoy its wonderful creations. This argument may appear strange today, but before the French Revolution the privileged status of kings and nobility and birthright of their children were primarily based on such claims. (p. 726)

Talent bestowed by the gods, then, was considered the prime determiner of expertise. Over time, the fallacies in this perspective were disclosed. Ericsson and Charness explain that "it is curious how little empirical evidence supports the talent view of expert and exceptional performance" (p. 730). They note that over the centuries, the talent hypothesis was inevitably challenged once it became evident that individuals could "dramatically increase their performance through education and training if they had the necessary drive and motivation" (p. 727).

Akin to the talent hypothesis is the intelligence hypothesis: highly intelligent people have the capacity to learn more, quicker. Over time, this trajectory leads to expertise. Ericsson, Krampe, and Tesch-Romer (1993) note that this hypothesis has little backing: "The relationship of IQ to exceptional performance is rather weak in many domains" (p. 364).

If expertise is not a function of talent or intelligence, what then are its determiners? Based on the research on expertise, we propose five conditions that must be met if a district or school wishes to systematically develop teacher expertise: (1) a well-articulated knowledge base for teaching, (2) focused feedback and practice, (3) opportunities to observe and discuss expertise, (4) clear criteria and a plan for success, and (5) recognition of expertise. We consider each condition briefly here and in depth in subsequent chapters. We further assert that these five elements are necessary and sufficient conditions to raise the level of teacher expertise across a district or school. Stated differently, if a district or school were to address these five elements, they would realize an increase in teacher expertise that would translate into enhanced student achievement.

A Well-Articulated Knowledge Base for Teaching

A well-articulated knowledge base is a prerequisite for developing expertise in a systematic way within any domain. Ericsson et al. (1993) note that the extant knowledge base has increased and is continuing to increase in a variety of domains. This accumulation of knowledge renders expert status more available to more people:

As the level of performance in the domain increased in skill and complexity, methods to explicitly instruct and train individuals were developed. In all major domains there has been a steady accumulation of knowledge about the best methods to attain a high level of performance and the associated practice activities leading to this performance. (p. 368)

As is the case with most fields of study, education has experienced exponential growth in its knowledge base, particularly regarding effective pedagogy. There have been many attempts to codify this knowledge base (see Hattie, 1992; Hattie, Biggs, & Purdie, 1996; and Wang, Haertel, & Walberg, 1993). We have organized that knowledge base into four related domains:

- Domain 1: Classroom Strategies and Behaviors

- Domain 2: Planning and Preparing

- Domain 3: Reflecting on Teaching

- Domain 4: Collegiality and Professionalism

These domains bear a resemblance to the very popular model of teaching proposed by Charlotte Danielson (1996, 2007). Her model includes the following domains:

- Domain 1: Planning and Preparation

- Domain 2: The Classroom Environment

- Domain 3: Instruction

- Domain 4: Professional Responsibilities

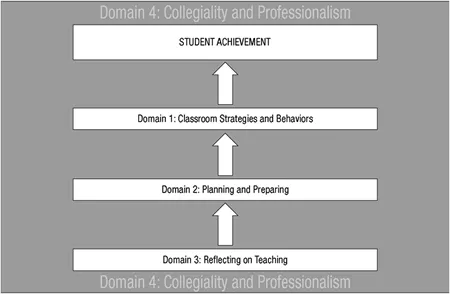

Although our domains bear some resemblance to Danielson's, there are significant differences in the assumed relationship between domains and the specifics within the domains. Danielson explains that her domains "are not the only possible description of practice" (p. 1). The same holds true for our model. That noted, we propose that our four domains not only represent a viable way to organize the research and theory on teaching, but also disclose some important causal linkages (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Relationship Among Domains

Figure 1.2 indicates that classroom strategies and behaviors (Domain 1) are at the top of the sequence and have a direct effect on student achievement. Stated differently, what occurs in the classroom has the most direct causal link to student achievement.

Directly below classroom strategies and behaviors is planning and preparing (Domain 2). As the name implies, this domain addresses the manner in which—and the extent to which—teachers prepare themselves for their day-to-day classroom work by organizing the content within lessons and the lessons within units.

Directly below planning and preparing is Domain 3—reflecting on teaching. By definition, most of the elements in this domain are evaluative in nature, in that teachers are considering their areas of strength and weakness with the overall goal of improvement. This domain has a direct link to planning and preparing. Teachers will probably improve very little in their ability to plan and prepare without carefully reflecting on their strengths and weaknesses. Without growth in planning and preparing, teachers will experience little growth in the classroom strategies and behaviors they employ. Finally, little change in what teachers do in the classroom will likely result in little change in student achievement.

The fourth domain—collegiality and professionalism—is not part of the direct causal chain that ultimately leads to enhanced student achievement. Rather, it represents the professional culture in which the other domains operate. This domain addresses behaviors such as sharing effective practices with other teachers, mentoring other teachers, and the like. When this domain is functioning well, all educators in a district or building consider themselves part of a team with a collective responsibility for students' well-being and achievement. In Chapter 3, we discuss these domains in depth.

Focused Feedback and Practice

The second element necessary for a district or school to systematically develop teacher expertise is focused feedback and practice. In their comprehensive review of the research on expertise, Ericsson and Charness (1994) identify "deliberate practice" as the sine qua non of expert development. Deliberate practice is a broad construct with a number of important elements. As it relates to developing teacher expertise, Marzano (2010a) has noted that deliberate practice can be thought of as a multifaceted construct. One central feature of deliberate practice is feedback. As Ericsson et al. (1993) explain: "In the absence of feedback, efficient learning is impossible and improvement only minimal even for highly motivated subjects. Hence, mere repetition of an activity will not automatically lead to improvement" (p. 367). This assertion is quite consistent with the findings reported by Hattie and Timperley (2007) from their analysis of 12 meta-analyses incorporating 196 studies and 6,972 effect sizes. The average effect size for providing feedback was 0.79, which they note is approximately twice the average effect size (0.40) associated with most educational innovations.

For feedback to be instrumental in developing teacher expertise, it must focus on specific classroom strategies and behaviors (Domain 1) during a set interval of time. For example, a given teacher might focus on specific strategies or behaviors from Domain 1 throughout a given quarter or semester. The feedback to that teacher during that quarter or semester would be on that specific strategy or behavior as opposed to the many other aspects of Domain 1 that could be the subject of feedback. The idea behind this degree of selectivity is that skill development requires focus. Feedback that involves too many elements or is too broad has little influence.

With focused feedback in place, teachers can engage in focused practice— another critical element of deliberate practice. Here the teacher practices the selected strategy or behavior experimenting with small variations in technique to determine what works best in his or her particular situation. We address specific approaches to focused feedback and practice in Chapter 4.

Opportunities to Observe and Discuss Expertise

One interesting aspect of expertise is that it manifests as nuanced behavior. Ambady and Rosenthal (1992, 1993) refer to this phenomenon as "thin slices of behavior." Relative to teaching, one can think of thin slices of behavior as the moment-to-moment adaptations a teacher makes regarding the use of specific strategies. Nuanced behavior, or thin slices of behavior, cannot be easily described but can be observed and analyzed. Consequently, opportunities to observe and discuss effective teaching are an important part of developing expertise among classroom teachers. If teachers do not have opportunities to observe and interact with other teachers, their method of generating new knowledge about teaching is limited to personal trial and error.

Although opportunities to observe and discuss expertise are not currently very common in K–12 schools, they are desired by teachers. In his book A Place Called School, which summarized data from 1,350 elementary and secondary teachers, Goodlad (1984) reported that "approximately three quarters of our sample at all levels of schooling indicated that they would like to observe other teachers at work" (p. 188). Similarly, in his article "Teacher Isolation and the New Reform," Flinders (1988) noted that although teachers work in isolation, they crave professional interaction with other teachers. This interaction involves both observing other teachers and interacting with them about teaching. Finally, the call for teachers to observe and discuss expertise is consistent with current discussions of professional learning communities (PLCs). As Louis, Kruse, and Associates (1995) note, one of the primary functions of the PLC movement is the "deprivitization" of practice.

In Chapter 5, we address ways to provide opportunities for teachers to observe and discuss expertise in depth. Briefly, though, we recommend that districts and schools provide opportunities for teachers to observe videotapes of other teachers, to observe expert teachers in their classrooms, to consult with expert teachers face-to-face, and to interact with their peers face-to-face as well as through synchronous and asynchronous technologies.

Clear Criteria and a Plan for Success

A critical aspect of deliberate practice is clear criteria for success. Quite obviously, relative to expertise in teaching, classroom strategies and behaviors (Domain 1) should include specific criteria as to what constitutes effective teaching. In Chapter 3, we describe 41 categories of classroom strategies and behaviors within Domain 1. For each of these 41 elements, scales (i.e., rubrics) are provided that describe novice-to-expert use of the element. Using these scales, teachers can track the development of their pedagogical expertise on specific elements over specific intervals of time.

It is tempting to embrace the position that teacher effectiveness regarding the strategies and behaviors in Domain 1 should be the sole measure of teacher performance. This approach would be a mistake. While the reasoned use of classroom strategies and behaviors is certainly a necessary ingredient of expertise, the ultimate criterion for expert performance in the classroom is student achievement. Anything else misses the point. This is depicted in Figure 1.2. Note that student achievement is at the top of the causal hierarchy. Stated differently, the ultimate criterion for successful teaching must be student learning.

In Chapter 6, we provide a number of ways to collect and use student achievement data as part of the criteria for successful teaching. We make the case that achievement data should be value added in nature. Value-added achievement data measure how much students have learned over a given interval of time. One type of value-added achievement data that might be used is knowledge gain. For example, the differences between pre-test and post-test scores on some common assessment or benchmark assessment would constitute a measure of knowledge gain for each student. Currently, knowledge gain is being used as a criterion for teacher evaluation in some districts. Other indices that can be used include residual scores and students' self-report of their knowledge gain.

With clear criteria in place for the classroom strategies and behaviors in Domain 1 and student value-added achievement, teachers can construct professional growth and development plans. These plans operationalize deliberate practice in that they describe how teachers will meet their goals and allow them to monitor progress toward their goals.

Recognition of Expertise

One characteristic of expertise in any field is that it takes a long time to develop. In fact, according to some researchers and theorists, it takes at least a decade—a fact that has been referred to as the "10-year rule" (Simon & Chase, 1973). Ericsson et al. (1993) have demonstrated the ubiquity of the 10-year rule. Regardless of the field, about 10 years of deliberate practice is required to reach expert status.

From the perspective of the 10-year rule, it is easy to conclude that acquiring expert status in teaching requires a high level of motivation on the part of aspirants. As Ericsson et al. (1993) explain:

On the basis of several thousand years of education, along with more recent laboratory research on learning and skill acquisition, a number of conditions for optimal learning and improvement of performance have been uncovered. … The most cited condition concerns subjects' motivation to attend to the task and exert effort to improve their performance. (p. 367)

It is probably unreasonable to expect all teachers, even the majority of teachers, to seek the lofty status of expert. Indeed, the natural human condition appears to be to stop development once an acceptable level of performance has been reached. Ericsson and Charness (1994) explain: "Mos...