![]()

Part I

Memory Boxes

![]()

Chapter 1

“It’s Not 30 Pesos, It’s 30 Years”

Just three days after the eruption of the estallido, French-Chilean singer Ana Tijoux released a one-minute video clip of her new rap song, “Cacerolazo,” whose infectious beat echoed the steady drum of pots and pans in the capital city and whose lyrics captured the ethos of the social revolution.1 The video got over 1.6 million hits on Instagram in its first day in circulation.2 The repetition of the words in the chorus, “Ca-ce Ca-ce Cacerolazo,” provides a rhythmic underpinning to the entire song, suggesting the force of the protests and the steady determination of the protesters. “‘#CACEROLAZO’ is a response to the social moment happening in Chile,” said the hip-hop artist in an MTV interview. “The idea was to reclaim the sound of the cacerola, or the pan, which was typically used in the protests against Pinochet. We’re returning to that form of protest with the banging of pans with a stick. In this moment, the sound signifies the unhappiness of the people. It’s very noisy but also very musical.”3 This was not the first time Tijoux’s music had accompanied a Chilean revolution. Her 2011 song, “Shock,” whose title references the economic “shock therapy” of Chile’s neoliberal experiment, became the anthem for the 2011–13 student protests.4

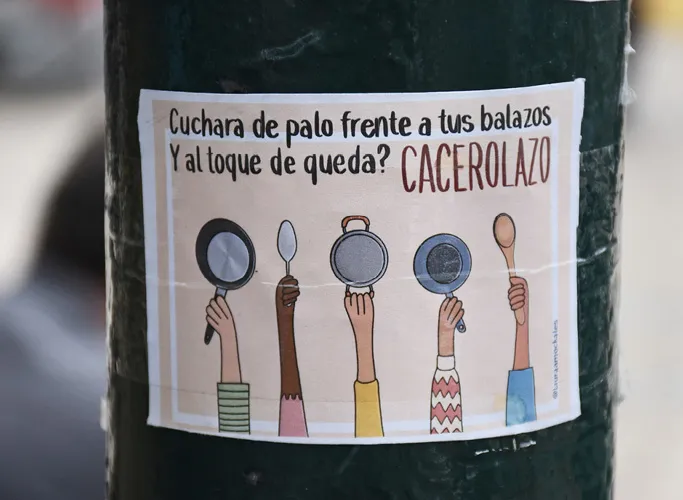

Figure 1.1. A colorful, ethnically diverse poster located on a lamppost at Plaza Ñuñoa reads, “Wooden spoons in the face of your bullets / And at the curfew? CACEROLAZO.” © Eric Zolov.

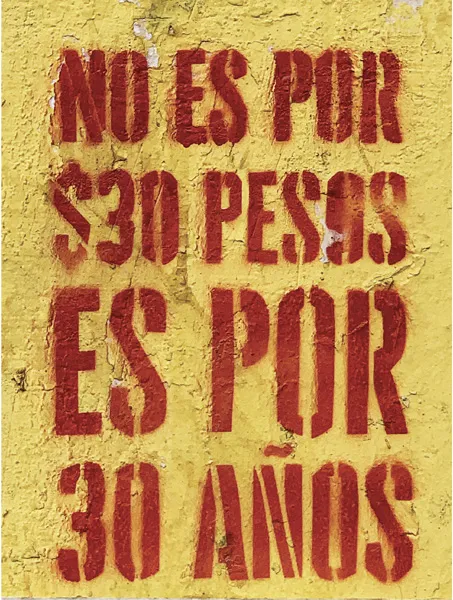

Tijoux’s “Cacerolazo” belongs to the rich tradition of Chilean protest songs. Through the central theme of the banging of pots and pans, the lyrics underscore the non-violent nature of the social protests. “We are not at war, we are alert,” raps Tijoux. “Get ready, girlfriend, Chile is waking up” (No estamos en guerra, estamos alerta / Vivita huachita, Chile despierta). The song draws a vivid image of the power of peaceful protest. In the face of bullets and water cannons, in the face of the entire machinery of the state stand the Chilean people with raised fists and cooking utensils. This theme is reiterated in various forms in different stanzas. (The video, which provides actual footage of the social revolution, including shots of burning subway stations and bonfires, provides a certain visual counterweight to this peaceful protest narrative). One poster that appeared in the first week of the protests featured five upraised hands, each holding a pot, pan, or spoon. The caption echoes Tijoux’s lyrics: “Wooden spoons in the face of your bullets / And at the curfew? CACEROLAZO” (Cuchara de palo frente a tus balazos / Y al toque de queda? CACEROLAZO) (figure 1.1). Even though the song came out just days after the outbreak of the social uprising, it captured the main motifs of the revolution: the deep frustration with the 1980 constitution, impunity for Pinochet-era crimes, and the radical inequities arising from the privatized or semi-privatized pension, education and healthcare systems. In one sentence, Ana Tijoux summed up the overarching theme of the protests: “It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years” (No son 30 pesos, son 30 años) (figure 1.2). This line, which traces three decades of social ills back to the economic and political legacy of the Pinochet era, provided one of the most important catchphrases for the 2019–20 social revolution.

The Legacy of Pinochet

On 11 September 1973, the Chilean armed forces bombed La Moneda Presidential Palace in downtown Santiago and toppled the democratically elected, socialist government of Salvador Allende. The US-backed coup ushered in the darkest period in modern Chilean history.5 General Augusto Pinochet assumed power, declared a state of siege, and made sweeping changes to the government, economy, and institutions.6 Pinochet’s first order of business was to root out leaders and supporters of Allende’s Unidad Popular (Popular Unity, UP) coalition. In a brutal three-week operation that took place between 30 September and 22 October 1973, the “Caravan of Death,” a military death squad, canvassed the country by helicopter, torturing and killing an estimated ninety-seven individuals associated with the Unidad Popular.7 In an effort to purge the landscape of remaining oppositional forces, the military junta then targeted political dissidents, left-leaning intellectuals, and members of left-wing political organizations, such as the MIR (Revolutionary Left Movement), the Communist Party, and the Socialist Party. During the early years of the civic-military dictatorship, more than three thousand individuals were murdered or “disappeared,” and more than thirty-five thousand individuals were imprisoned and tortured.8 The country was the locus of an estimated 1,132 centers of detention and torture.9 Most of the crimes took place between 1974 and 1977, the period in which DINA, the National Intelligence Directorate or secret police, was operative. After Pinochet lost in a plebiscite in 1988 to determine if he should remain in power, Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin was elected by popular vote, and Chile entered a period of “democratic transition.”

Even though democracy was restored in 1990, the arm of justice has been slow. The Pinochet regime passed an amnesty law in 1978 that granted impunity to individuals who had committed human rights violations during the first five years of the regime, an amnesty that remains in force today.10 Despite the transition to democracy, Pinochet retained the position of Commander-in-Chief, a position he would hold until 1998, and much of the government and military remained in the hands of his supporters.11 (The legacy of the regime is still apparent today. In one prominent example, President Sebastián Piñera’s cousin Andrés Chadwick, who was an avid supporter of the Pinochet regime, served as Interior Minister from March 2018 to October 2019, when he was forced to resign under pressure.)12 Given the judicial constraints he faced, President Aylwin vowed to deliver “the whole truth, and justice to the extent possible.”13 The first truth commission report, the Report of the Chilean National Commission on Truth and Reconciliation, known as the Rettig Report, was published in 1991. The mandate of this commission was narrow, covering only crimes that resulted in death or disappearance (and thus the presumption of death). Furthermore, only victims, and not perpetrators, were named in the report. The scope of a subsequent study, the Report of the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture—or the Valech Report—was broader, covering cases of imprisonment, torture, and sexual violence. The Valech Report was published in November 2004, but the extensive documentation behind it, including testimonies with the names of perpetrators, remains legally classified for fifty years from the date of the release of the study.14 According to the investigation, 94 percent of political detainees were tortured, a statistic that underscores the extent to which torture was a regular aspect of the military dictatorship.15 “Torture by members of the Armed Forces and Carabineros (paramilitary police) was a generalized practice on a national scale,” concluded the United States Institute of Peace.16 Because of the fifty-year veil of secrecy, crucial evidence and testimony gathered by the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture will not be available to prosecutors until 2054, which means that many survivors and families of survivors will not see justice in their lifetimes.17

Figure 1.2. This stencil, located on a wall on Avenida Providencia, echoed a line of the spoken-word rap song, “Cacerolazo,” from the video montage by Ana Tijoux that was released on 21 October 2019, three days after the start of the uprising. “It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years” quickly emerged as the central slogan of the estallido. © Terri Gordon-Zolov.

In the first ten years following the 1988 plebiscite, few inroads into justice were made. Pinochet’s house arrest in the United Kingdom on 16 October 1998 for crimes against humanity marked a turning point.18 In a landmark case that year, the Chilean Supreme Court held that the amnesty law did not apply to instances of disappearance because such cases were ongoing and more properly belonged to the domain of “kidnappings.”19 Furthermore, courts began drawing on national and international human rights discourse to get around the amnesty law. As a signatory to various international treaties, such as the 1978 American Convention on Human Rights, Chile is bound to respect provisions concerning fundamental human rights and crimes against humanity.20 On numerous occasions, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has called for the repeal of the amnesty law on the grounds that it breaches the provisions of the American Convention on Human Rights, in particular the articles concerning the rights to life, humane treatment, and juridical protection.21 In the case of Almonacid-Arellano v. Chile in 2006, which covered an extrajudicial murder of a Communist Party member, the Inter-American Court declared the amnesty law to be “overtly incompatible with the wording and the spirit of the American Convention” and, therefore, lacking in “legal effects.”22 When she took office as president in 2006, Michelle Bachelet, who herself was imprisoned and tortured under the Pinochet regime, vowed to overturn the amnesty law.23 On 11 September 2014, the forty-first anniversary of the coup, she urged Congress to take up a 2006 motion to repeal the amnesty law. “Many of them have died waiting for justice. Many have died in silence,” she said in regards to survivors and families of survivors. “We’ve had enough of painful waiting and unjustified silences. This is the time to join together in the search for truth.”24 As had happened before, the proposal failed to garner sufficient support in the legislature. Despite the amnesty law, judges continue to make convictions based on the grounds of inviolable human rights...