Marianne Kac-Vergne: On the MUBI platform, there is a beautiful quote that is attributed to you and I was wondering if it is actually yours. ‘All my life, I’ve been looking at films which foreground men and I wanted to make films where men are peripheral, in the background, the way women usually are.’

Vivienne Dick: That’s right.

MKV: Your films all feature mostly women and sometimes only women. What interests you about filming women?

Vivienne Dick: I was interested from the very beginning in the fact that women in our culture are not full and equal subjects. Now, at that time I didn’t use that word ‘subject’, but that’s what it was. I felt that the way women were represented in society was biased and limited. So I decided, well, I’m not going to be adding to all this kind of material. I’m going to just make films about women. I’m a woman. I’m interested in women, and so I’ll make films about women. It’s as simple as that. So I have men sometimes come in on the edge of the frame and that’s fine.

Céline Murillo: The women you’re filming are so different. In Guerillere Talks (1978), Lydia Lunch is all curves and hyperfeminine, while the other extreme is the very lean and twiggy Pat Place.

Vivienne Dick: Lydia is feminine, but she’s strong and tough. She’s feminine, but she’s like a demon as well. She’s not a pushover by any means. She has the power. She’s got the control always. Pat is more passive, and very androgynous looking, which is interesting to me. The woman who is the dancer at the beginning of Red Moon Rising (2015) also looks amazing.

CM: But did you cast Pat Place and Lydia Lunch because they were so different?

Vivienne Dick: I wasn’t thinking about casting when I was making Guerillere Talks. I was just interested in both of them. I’d seen Lydia perform in the No Wave band Teenage Jesus and the Jerks and I’d never seen such a creature. Listening to this music, it seemed wild to me. And then seeing these women I’d never come across before was fresh and different. So I just gravitated towards them and some others – like Adele Bertei and Anya Phillips. I simply approached Lydia, for example, and asked if I could film with her. And that was a way to get to know her.

CM: In New York, there were a lot of women in the No Wave groups.

Vivienne Dick: That was what was really exciting for me when I moved to New York and when I discovered the music scene and its incredible energy. Many of the women were involved in that scene not just as singers, but playing instruments and even having their own bands. This was replicated elsewhere too, in other kinds of music and in other arts; there were photographers, women involved with theatre, female choreographers and dancers, this incredible array of women doing all kinds of creative work, the likes of which I had never experienced before. It was very exciting.

CM: Why do you think that there were so many women in these groups and that there was no difference between cinema and the other arts in terms of the participation of women?

Vivienne Dick: New York in the late 1970s was going through a highly creative period. There were a lot of women involved in the arts, in performance art as well, like Yvonne Rainer, who was a filmmaker, a dancer and a performance artist, for example. I used to attend Anthology Film Archives and saw quite a lot of American experimental films made by women, which was new to me. Then there were other women who were highly successful, in dance, too, such as Twyla Tharp, Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs. And Meredith Monk was very interesting as well. I’d never seen any performer like her before in the way she used the voice in theatre.

MKV: Were you attracted to the No Wave style because there were so many women?

Vivienne Dick: No, I was attracted to the music, particularly to the very avant-garde, experimental noise bands which I found very exciting.

MKV: Were there links between the No Wave bands and arts collectives and the feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s?

Vivienne Dick: A number of the women who were involved in the music scene at the time, people like Pat Place or Adele Bertei, were lesbian or queer. They and others, like Lydia Lunch, were very strong and a type of woman that I had not encountered before. So I was intrigued by that: that’s what made me want to film them in the very first film, Guerillere Talks.

MKV: Were there official or institutionalized links with more feminist or more political groups?

Vivienne Dick: There wasn’t any really, but I knew Claire Pajaczkowska, who lives and works in London now as a professor at the Royal College of Art, and who was involved at the time in a feminist magazine called the Heresies Collective that produced really interesting work on art and politics. The magazine was quite radical in content and layout and the work was very collective. We used to have meetings on my rooftop to discuss feminism and possible collaborative work in film, and Claire was the theoretical person in the group. That’s where the title Guerillere Talks comes from (we had been reading Monique Wittig’s book, Les Guérillères). Claire encouraged me to continue making films. Some of the feminists at that time were suspicious of the women who were involved in the music scene because of the way they dressed and used makeup. Many feminists at the time dressed down and were opposed to wearing sexy clothes or whatever, but on the punk scene, women dressed to please themselves, sexy or otherwise.

MKV: Going back to what you said about many of the members of the scene being lesbians, the feminist movements of the 1960s especially and some of the 1970s have been criticized for being quite hostile to lesbianism. And they’ve also been criticized for being quite white-centred, not necessarily including very many women of colour. What do you think of that? Was this also true in the No Wave movement with women of colour?

Vivienne Dick: There weren’t many women of colour on the scene, apart from a very good friend of mine called Felice Rosser, who was one of the few who was around at that time. She’s a musician and she’s featured in my last film [New York Our Time (2020)]. New York has always been segregated. But then something changed when hip hop came downtown. Some filmmaker friends of mine were hanging out in the Bronx and Charlie Ahearn started working with the very early hip hop people. Michael Holman, who used to play with Jean-Michel Basquiat in a band called Gray, was the person who first brought the bands downtown, very close to where I was living in fact, to a small basement club called Negril. I went along to some of those early performances. It was really exciting to be there at the very beginning of hip hop.

CM: But did it really change something in the multi-racial makeup of the neighbourhood, or was there just one place that had hip hop and all the rest was punk?

Vivienne Dick: It did not change the racial makeup of the neighbourhood but it did become more diverse with more Black, white and gay people mixing in some clubs – and new, larger venues opening all the time. People were very excited about the new rhythms of hip hop. Blondie, for example, had been listening to hip hop and she brought out a song called Rapture that was influenced by that sound. The thing is, the music was changing all the time. You had this avant-garde, austere kind of music, and you had the very simple Ramones-style punk music. There was a cross-pollination between minimalist music (Rhys Chatham, Glenn Branca) and punk, and this led to a lot of guitar sound – Sonic Youth, for example. And then after a few years, it became more rhythmical, with a more African influence, especially from Nigeria, Fela Kuti for example. Reggae had always been around and the music was becoming what they call ‘postpunk’. Bands like Konk and a very popular band that Pat was in, the Bush Tetras, were using a more funky kind of sound.

MKV: In an interview, you mentioned the community gardens in New York with many Puerto Ricans or Hispanics. Was there any interaction between artistic groups and the community garden movement?

Vivienne Dick: There were plenty of Puerto Rican and Caribbean people around the Lower East Side but a lot more in Brooklyn. Interaction was limited although it developed later on, especially in the larger gay clubs, and also when the graffiti artists who worked on the subways began to be shown in downtown galleries and become well-known. Early on, I was teaching English in a Central American school on 14th Street. So I knew loads of people from the Dominican Republic and they brought me to some merenque or salsa events in social clubs.

MKV: But the links were mainly musical rather than through film?

Vivienne Dick: Yes. I only know of one Hispanic filmmaker from that time – Manual DeLanda – in fact he is from Mexico.

CM: The ABC No Rio building was right in the centre of the Hispanic neighbourhood. Was there any participation from the Hispanic community?

Vivienne Dick: There probably was over time. But I really do not know much about that. I do know that Charlie Ahearn and Robert Cooney and his friend Jorge Mendez spent a lot of time in the South Bronx exploring the hip hop scene. Robert was a filmmaker and an anarchist. They made beautiful silk screen posters, Charlie made his well-known film Wildstyle (1983) with the rappers, graffiti artists and breakdancers from there.

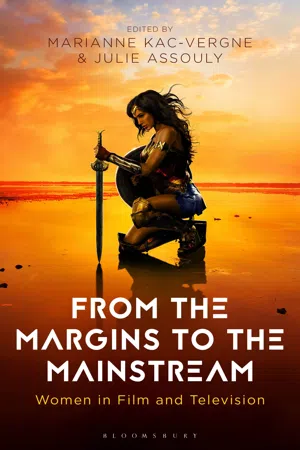

MKV: The title of this book is From the Margins to the Mainstream: Women in Film and Television. Do you think that actually applies, that women have gone from the margins to the mainstream, or not? Would you say that women have been able to enter the mainstream?

Vivienne Dick: It depends on what you want. Not everyone wants to make mainstream films. I am not sure I fit into a mainstream model. I don’t even work with scripts, by choice.

But there are more women around now who are successful filmmakers and who work in the mainstream. It is a complicated issue as I feel that it is still very hard for women to get support for their films, but it is better than it was before. Women as well as men are more conscious of these difficulties. Personally, I have to be true to myself and make the kind of work that feels authentic to me whether that is going to be mainstream or not. But it’s extraordinary to me how work that I made many years ago, that was so low budget and so visceral, is still being shown in places like the Museum of Modern Art here in Dublin, who bought two of the works. When the work is shown today and I meet young people who come along from art colleges and film schools and who tell me that they can relate to this work, that is really interesting to me.

CM: Where are your new films released now, in art shows or in the cinema?

Vivienne Dick: I prefer to show my work in the cinema but sometimes it work...