![]()

Part I

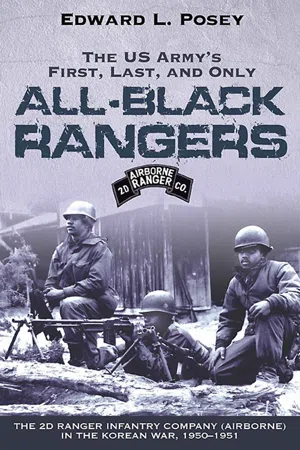

The soldiers of the all-black 2d Ranger Infantry Company (Airborne), like other black units, were nicknamed the “Buffalo Soldiers.” There is more than one explanation of how the nickname came to be, but a commonly accepted account is that sometime around 1870, the 10th Cavalry Regiment was given this nickname by the Cheyenne Indians who “saw a similarity between the curly hair and dark skin of the soldiers and the buffalo.” 1 The nickname gradually came into usage whenever referring to any black soldier fighting the Plains Indians, and was “so popular among the members of the 10th Cavalry that they adopted the figure of a buffalo as a prominent feature of their Regimental Crest.”

During World War I, the soldiers of the 92d Division adopted the nickname, and the unit was called the Buffalo Division. Each member wore a shoulder patch on his uniform adorned with the solitary figure of a black buffalo. In 1942, the 92d Division “kept the nickname and apparently acquired a live young buffalo as a mascot.” 2

In 1950, throughout their training days at Fort Benning, Georgia, and before the Buffalo Rangers who were to fight in Korea went overseas, “Buffalo” was a term of respect. In it there was solidarity. We are Rangers AND we carry the traditions of earlier Buffalo soldiers—we are strong, we are resilient, and we are united to destroy the enemy.

![]()

Chapter 1

Training at Benning

Sometime around the 25th of September 1950, rumors started circulating around Fort Bragg, North Carolina, that a Ranger recruiting team was on base looking for a few good triple volunteers: soldiers who had volunteered for the Army, the Airborne, and to see combat as a Ranger. Triple volunteers committed to: (1) a minimum of three years of service, because there was no draft in operation at the time; (2) parachute and glider school that produced two sets of wings when satisfactorily completed; and (3) combat in Korea, which is where all Ranger volunteers were headed. Fort Bragg was the home of the 82d Airborne Division, a major portion of the United States strategic forces.

The 82d Airborne Division was the only combat-ready unit still stateside when the call for Ranger volunteers went out. The 11th ABN was just getting reorganized after returning from Japan and was stripped of personnel to bring the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team (ARCT) up to strength in time for the Sukch’on and Sunch’on jump in October 1950. The main post at Fort Bragg could not hold all of the units assigned to it. The majority of the 82d was located in the main post area, but upon the reactivation of the 325th Glider Unit, the 325th was moved into the old Recruit Training Center (RTC) located across Highway 24, where non-airborne engineer units and the reception center for personnel newly assigned to Fort Bragg also were housed.

The black troops were located in the Spring Lake cantonment area on the south side of Highway 24, near the small town of Spring Lake. Murchison Road, the other main road leading into Fayetteville, North Carolina, is adjacent to this area and ran through the main black area of the city. It usually took about a day for the “official” information to come from the main post to the Spring Lake area, and two days for information to reach the RTC area. The rumors were usually passed at the Division schools because the housing and recreation area on post and in the community were “separate but equal.” Some of the black troops had regular duty assignments on the main post, and this was another way in which word of the recruitment of blacks for Ranger training was disseminated. The main black units in the Spring Lake area were the 3d Battalion, 505th Infantry Regiment; the 80th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion (AAAB); and the 758th Tank Battalion (Airborne). The 758th was kept on “jump status” and was to provide tank support to the 82d Airborne Division in case of war. Throughout September 1950, it grew obvious that we were going to be sent overseas, because we were the only unit in the 82d Airborne that was over-strength.

Corporal James Fields, who was recruited from the 80th AAAB, describes a typical Fort Bragg recruitment session as follows:

Like Fields, many were apprehensive and excited—but subdued. Orders from division headquarters usually arrived so late to the company at the Spring Lake cantonment that the normal procedure was “Hurry up and give me your decision, now!”

That decision sent men from Fort Bragg to Fort Benning in Georgia, where six weeks of Ranger training began. At that time, the Rangers training at Benning either belonged to the all-white 2d Ranger Company or the all-black 4th Ranger Company. At Benning’s Harmony Church cantonment area, both units trained together but lived separately. The 2d and 4th would exchange unit designations on 13 November 1950. From that date until its inactivation on 1 August 1951, the all-black unit was known as the 2d Ranger Company.

The Harmony Church cantonment area was a small living and training area, for Rangers only, at the far southeast corner of the post about ten miles from the jump towers. It was near the town of Buena Vista. Toward the end of World War II, Harmony Church had been the housing area for the Officer Candidate School (OCS) and the compass course areas. The 25th Infantry Regiment was located in “Sand Hills” and the Small Arms Ranges and Jump School were in the South Post area. The black troops’ area consisted of the last quadrangle, a small PX, a movie theater, and a barber shop.

The bus could go directly to town from Harmony Church or come up to a variety of locations on the main post. The local custom of blacks riding at the rear of the bus prevailed. The only time the Rangers needed to come on post was for range firing and parachute training. The 3d Infantry Division was trained there before deployment to Korea. The 11th RCT acted as school troops.

Physical Conditioning and Training

The training at Fort Benning was rigorous. The day usually started with a three- to five-mile run before breakfast nicknamed “The Airborne Shuffle.” Even before entering the mess hall, there was physical training (PT): a pull-bar was posted over the door to the mess, and only after doing five or more pull-ups were you allowed to enter the mess hall. Marching to the training sites with all equipment was routine. The trick of going without a lot of water was learned very early. You put a small pebble under your tongue to stimulate the saliva glands, causing the mouth to stay wet and lessening the need for water. These were skills we would later rely upon on the battlefield.

All men assigned to Ranger Training Command were already qualified paratroopers and had passed the standard PT test with a score of at least three hundred points. The standard test consisted of five hundred points. The average trooper could easily make the three hundred points required to pass. The pull-ups were usually the most difficult part of the test. The physical run was no problem—except with a hangover. Very few fell on the runs. Usually, the Airborne “Jodie” cadence was modified from “Airborne—all the way!” with the word “Ranger,” as follows:

Those of us who had come from Fort Bragg were in good physical condition. Back at Bragg, the troopers of the 3d Battalion frequently ran about five miles down to Pope Field from the Spring Lake area.

From October through November, the Rangers conducted familiarization firing of most of the weapons (.45-caliber pistol, carbine, M-1 rifle, Browning automatic rifle, or BAR, and .45-caliber submachine gun), including a few Russian and Chinese weapons such as the Chinese grenade (which used a pull string). The Rangers moved on to tactical training, starting at the squad and platoon levels. Ranger recruits learned map reading, which included U.S. military maps, foreign maps, and maps of Korea printed by the Japanese when they had occupied the peninsula. Rangers also learned land navigation, night patrol/day patrol methods, interdiction operations, phone and electric power line sabotage, assassination methods, improvised killing, martial arts, hand-to-hand combat and raid procedures, and completed demolition training, water training, and small boat and rubber boat (RB-15) training.

The training day was usually twelve and sometimes as long as fifteen hours. Soldiers got used to walking in their sleep during the long road marches. Sometimes the column would turn but a sleepwalking Ranger would continue walking until he hit a tree or walked into the wood line. Rangers tried to drink enough coffee before a march to stay awake, but not so much that they would need to stop, at the risk of being left behind or becoming a skunk attraction.

The roughest training problem was a company raid to blow up a big bridge deep in enemy territory. This exercise was held near the town of Buena Vista on the far side of Fort Benning. We must have walked twenty miles that night (there was a real sleepwalker problem that evening). The action started when Lieutenant James Queen hit a Bouncing Betty style of trip flare on the bridge just as the charges were set, which gave the alarm. This helped to clear the bridge in record time. We took off down the railroad tracks on the escape route and successfully passed the training exercise.

During one of the exhausting, 24-hour, platoon-size patrols, the First Platoon commander fell asleep and failed to post adequate security. It just so happened that Colonel John Gibson Van Houten, the Ranger Brigade Training Commander, came out to check on this training problem in person. He walked through the majority of the platoon area without being challenged. If a mistake like this had happened in combat, the entire platoon could have been killed. So the platoon failed and had to repeat the grueling patrol. When the unit got back to the barracks, Colonel Van Houten called in all of the company officers for a critique. Needless to say, everyone was extremely embarrassed. He ended his critique with an often-heard racial slur, “You people won’t fight when you get to Korea!” This caused immediate anger among the company officers. All of the previous racism they had experienced seemed to be summed up in this one, biting criticism. The innuendo behind the words “you people” always provoked images and emotions of racism. The officers bit their tongues and offered no excuses, but resolved never to be in such a shameful position again. And it never did happen again. Still, that one mistake left a sting still not forgotten. The colonel’s remarks were never passed on to the men because it was the officers’ leadership failure that had allowed this situation to occur. But copies of the first award orders from combat were later sent to Colonel Van Houten as proof that his assessment of the unit’s probable conduct during combat had not been accurate.

During Ranger training the word was that the North Koreans were on the run and the action in Korea was just about over: all of the men would be home for Christmas, and the trainees at Benning would never see combat overseas. Many of us were disappointed. But on 3 November 1950, the Chinese entered the war and the UN Army was in full retreat. It was now inevitable that the Rangers of 2d Company would see combat in Korea. Corporal James Fields attests that “2d Company pushed itself to the limits, training day and night to reach top combat efficiency. Under the command of First Lieutenant Warren E. Allen, his career officers and top-notch NCOs molded us into a cohesive fighting force in a very short time. Our training never let up.”

Allen, one of the most well-respected officers to emerge from the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, was all business. The Rangers under his command often felt that it was because of his leadership that they were successful. Many believed the 2d Ranger Company was designed for Allen’s leadership. Typically, Allen would hold the men in the bayonet “long thrust” position until their arms quivered. Whenever there was time for refresher PT, it always included bayonet drill practice to instill a spirit of confidence and aggressive behavior until it became an automatic response. He despised common barracks profanity. If one of his men made a mistake and used such words in his presence, he would get an angry stare from Allen, followed by a quick rebuke. If you were an enlisted man (EM) and used profanity in the presence of a woman, you were sure to end up on KP or digging a 6’ x 6’ garbage dump. If you were an officer, you got the next miserable detail that came up. Corporal Samuel “Shorty” Payne remembers Allen as a “no-nonsense leader who gained respect from the men and noncommissioned officers under him. He had a cadre of men that rallied and supported him. Allen would push, push, and push some more so that the men in the first black Ranger company would be the best that the Army could offer.”

On 13 November 1950, all members of 2d Ranger Company were given a small Ranger tab to display on their uniforms. This tab was new and held no meaning for the Rangers, some of whom were insulted by the award. A group of Rangers went into town to the local Army-Navy Store and bought surplus World War II Ranger Battalion scrolls, had them modified to change “Battalion” to “Company,” and wore these custom-made insignia with pride.

During November, the Rangers conducted several increasingly difficult company-sized training missions. One exercise involved traveling through swamps and making a dawn raid on a fixed-wing light aircraft field. The swamp was negotiated with a compass heading. The company traveled in single file, and the swamp area was so dense and the night so dark that the Rangers could use a flashlight and not be seen from more than fifty feet away. It took the Rangers four to five hours to travel less than three miles. They were extremely lucky that they did not lose anyone. The Rangers came out directly on the airfield at the break of dawn and hit it before the force tasked to hold the position arrived to defend the airfield. Another milestone was achieved.

Another of the company-sized training missions was crossing Victory Pond and making an assault landing on the opposite side. The November wind was offshore and the weather was cold. The training film shown the night before made the exercise look straightforward: cross two rifles and secure them, then take two shelter halves to make a raft. Each Ranger was ordered to put his equipment on the raft and push it in front as he swam. With the rafts, the men had to paddle upstream, reach a certain landing point, scale the cliffs while carrying combat gear, and continue on with the assault mission.

The actual exercise did not unfold as it did in the training film. The Rangers looked bad in planning, coordination, and execution. The company failed to get to shore in a satisfactory manner. We ran into the following unanticipated problems:

—Very few of the men were good swimmers, and many of the men did not have even the basic ability to swim unassisted for a distance of fifty feet, which caused some anxiety in the ranks;

—Very few of the troopers had previously received boat or raft training. Even those who had gone to Combine II in Florida or the R&R Camp at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, lacked this type of training;

—We used small 4-to-5-man rafts, with small wooden paddles;

—The rafts were not loaded according to the troopers’ swimming and climbing ability, such that each raft had both experienced and inexperienced swimmers;

—We had to scale a ten-foot cliff of red Georgia clay. The walls of the cliff became extremely slippery, making it a...