9

Observation Skills

The Foundation of Activity-Based Intervention

“Observation goes hand in hand with teaching; neither yields the optimal result by itself.”

(Halle & Sindelar, 1982, pp. 44–45)

Accurate and directed observation is essential to the delivery of quality intervention. ABI is no exception, and consequently, gathering critical data through either structured or unstructured observation on what children do and how they do it is essential to this approach. Observation prior to intervention is necessary to determine what to teach and how to teach it. During intervention, observation is necessary to determine the child’s response to the intervention provided. Observation of the child’s responses allows the interventionist to make changes to the teaching methods and strategies when the child does not make expected gains or to move on to teaching new skills when the child meets the established criterion for targeted goals or objectives.

Observation has been an integral part of ABI from its inception in the 1970s. While developing one of the first community-based inclusive EI programs, Bricker and colleagues found that observing how typically developing children responded to each other, to adults, and to instructional activities provided enormous insight into how children learn. These observations enabled the change from using a highly structured approach to an approach that took into account children’s interests and motivations. To move to more authentic approaches, child-directed activities, daily routines, and play became the primary vehicle for the delivery of intervention (Bricker, 2000). Even as the ABI approach has evolved over the years, observation continues to be critical to its implementation.

The act of observation can be defined as a process of regarding attentively or watching while the verb observe means to regard with attention to see or learn from the act of watching. These definitions are important because they emphasize the directed nature of the regarding or watching. In this chapter observation refers to the purposeful and careful watching and listening to gather accurate and useful information on children’s behavioral repertoires. For our purposes it is useful to dissect observation into critical elements that should be considered when using observation in ABI. These elements include observer(s), purpose, structured or unstructured, physical and social setting and objects, data gathering, and analysis.

Observer(s) refers to the individual or individuals who are assigned the task of observing a child or children. To be an accurate observer generally requires training and experience in order to separate important data from information that may not enhance understanding. At the very least an observer needs to be present, able to focus on the purpose of the observation, and take notes or complete a form that accumulates relevant information.

Purpose refers to why the observation is being undertaken. Most children engage in a myriad of actions and activity—usually too many for any observer to take in and record. Consequently, most observers require that some focus or purpose direct their watching and listening.

Structured and unstructured refer to whether the observer has the freedom to record any and all observations (e.g., on blank paper, during video recording), or whether the observer is using a form that guides the focus and content of the observation. For example, a structured observation might be recording a language sample that entails entering all sounds and words uttered by a child but not include recording social interactions or motor movements. An unstructured observation might require recording all of a child’s responses during 20 minutes of free play time.

Physical and social setting and objects refer to reporting information on where the child was observed and who and what was present during the observation. Even in structured observations such as entering data on a form that tracks peer interactions during group time, it is usually important for the observer to note information about the child’s physical and social environment. Who and what is present may have significant effects on children’s behavior.

Data gathering refers to what the observer actually records during the period of the observation(s). For some structured observations, observers may note the number of times a response occurs. For unstructured observations, observers may keep a running record of the child’s behavior during outdoor playtime and the conditions under which the response occurs. The type of data collected is largely determined by the purpose of the observation.

Finally, analysis refers to how the data or information gathered are aggregated or assembled for presentation and use. If numbers of responses by conditions are recorded, the analysis may entail a count of responses by condition (e.g., “The child interacted with peer 1 by snatching a toy three times over a 15-minute observation, interacted with peer 2 by answering her communicative request five times, and did not interact with peer 3.”).

Consideration of these elements assists in understanding that quality observation demands careful and accurate watching and listening with a clear purpose in mind. Each of these elements is described in the following example.

Observers: Katie’s team members

Purpose: To gather information on Katie’s developmental repertoire

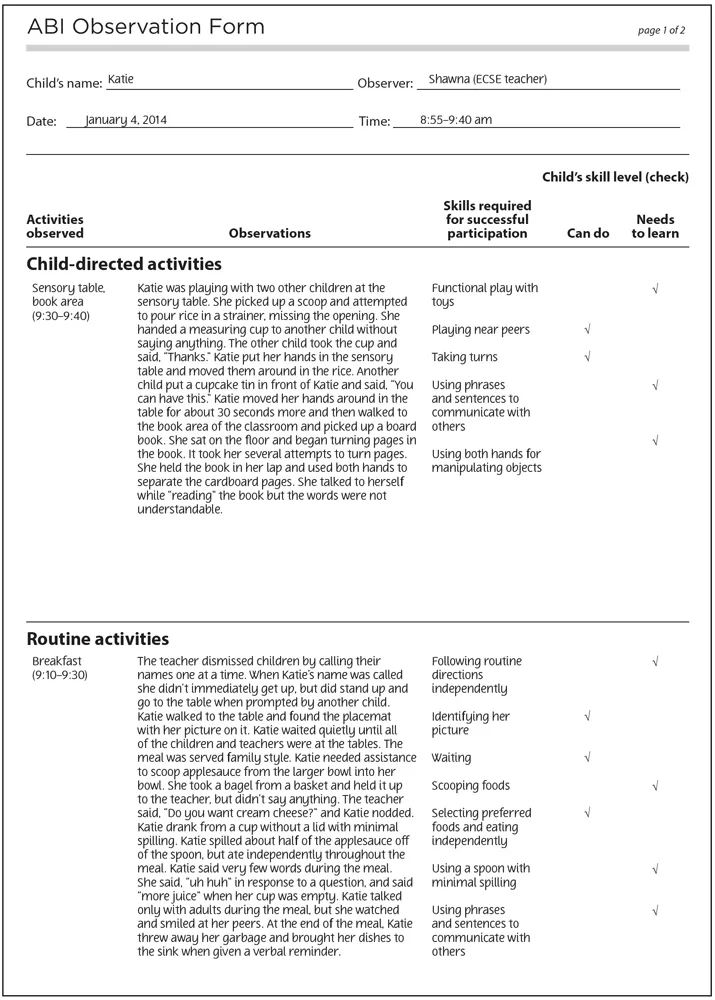

Structured observation: The team was specifically concerned with gathering information on Katie’s responses while at school during child-directed, routine, and planned activities using the ABI Observation Form (Figure 9.1)

Setting: Classroom with other children and staff

Data gathering: Observation of Katie while she engaged in daily routines and play

Analysis: Consideration of multiple observations and consolidation of findings into an intervention plan

Katie’s team (the observers) conducted a series of 30-minute observations. The purpose of the observations was to gather information on what she did during classroom routines and activities (physical and social setting). The team used the ABI Observation Form to structure the observations during the 30-minute sessions (data gathering). After 2 weeks, the team aggregated the data from the forms (analysis). These aggregated data gave the team members a clear picture of what Katie did during classroom activities and under what conditions. These findings were used to begin an IEP for Katie. The team planned to complete Katie’s IEP after the baseline assessment was completed by staff and by parents using a family friendly measure.

Carefully planned observations such as those conducted by Katie’s team are essential to the application of authentic intervention approaches such as ABI. The remainder of this chapter offers an overview of high-quality observations and describes how observation can be used with each component of the linked system, which serves as the framework for ABI.

CHARACTERISTICS OF HIGH-QUALITY OBSERVATIONS

High-quality observations of young children with special needs within an ABI approach need to meet several important criteria—criteria that reflect the elements of observation discussed in the previous section. First, the team should determine the purpose of the observation before collecting information. The purpose needs to be decided in advance as it will have an impact on how the observation is conducted, including the setting and length of the observation, as well as the type of information or data collected during the observation. Child-related factors need to be considered as well. For example, an observation of a child with significant behavior challenges may require a different set of observation tools and methods than an observation of a child with expressive communication delays.

The second criterion is that observations should be conducted within familiar, typical environments (Bagnato, 2005; Bagnato, McClean, Macy, & Neisworth, 2011). For example, when determining eligibility, the team should observe the child in authentic environments (e.g., home, child care setting, community preschool classroom) rather than in unfamiliar settings (e.g., clinic, testing room). Observers should be as unobtrusive as possible to avoid affecting the child’s behavior. Ideally, the observer should be familiar to the child and setting (e.g., classroom teacher) to minimize disruptions to the typical routines and activities being observed.

Third, observations should be of sufficient length to provide accurate or valid information about the child’s skills. The length of the observation will depend on the purpose of the observation. For example, if the purpose is to observe a toddler’s self-feeding skills, it may be appropriate to observe for 20–30 minutes during the family’s mealtime. If, however, the purpose is to observe how a preschooler with autism manages transitions between classroom activities, it may be necessary to observe several 5–10 minute periods during an entire school day.

A fourth criterion requires team members to conduct multiple, ongoing observations (Bagnato et al., 2011). One observation may provide an accurate glimpse of the child’s typical behavior, or it may not. Children have variable patterns of behavior dependent on a variety of factors including setting events (e.g., whether they are hungry or tired), time of day (e.g., early morning may be better than late afternoon), the activity itself (e.g., structured vs. unstructured, teacher-directed vs. child-initiated, familiar vs. unfamiliar), the child’s interest in the activity, and people involved in the activity (e.g., preferred peers, familiar vs. unfamiliar adults). Thus, it is generally important that team members conduct multiple observations in and across different settings, at different times of day, in a variety of activities, and during interactions with adults and children.

Fifth, observations should be recorded according to predetermined directions and rules. The observer should be clear about information relevant to the observation given its purpose and should record this information in an organized fashion that can be subsequently interpreted by the team. The recording method should match the purpose of the observation. Although observational recording methods are beyond the scope of this book, these methods might include anecdotal notes, video recordings, checklists (standardized or informal), or more specific behavioral data collection methods (e.g., interval, duration, latency). Good sources of information on these methods include Assessing Infants and Preschoolers with Special Needs (McLean, Wolery, & Bailey, 2003) and Applied Behavior Analysis for Teachers (Alberto & Troutman, 2012).

A final criterion is that observation results should be summarized and interpreted in combination with other relevant information (e.g., parent report, results from a curriculum-based measure, weekly data collection). Data gathered should be viewed in concert with other information available to the team. Combining data and information from multiple sources will likely provide the most accurate and complete picture of the child’s behavioral repertoire.

The intent of this section is to emphasize that quality observation takes thought and effort that, in turn, requires an expenditure of time by team members to plan, execute, and subsequently use the collected information to understand what children can do and determine what developmental targets should be addressed by intervention efforts.

Time expenditure raises an issue that often dominates EI/ECSE staff concerns. One of the more frequent problems noted by interventionists and specialists is the lack of time to engage in observation and data collection or in group discussions about how to proceed with a child. The dilemma faced often by staff is that the da...