![]()

Part One

Gender, Law, and Urban Slavery

![]()

Chapter One

Sites of Enslavement, Spaces of Freedom

Slavery and Abolition in the Atlantic Cities of Havana and Rio de Janeiro

He knows by listening to people in the neighborhood that both the defendant’s slaves and [Josepha’s daughter Maria] are ill-treated . . . and he . . . has heard that this has been published in the daily newspapers.

—José Antônio Alves Rodrigues, witness for Josepha Gonçalves de Moraes, Rio de Janeiro, 23 July 1884

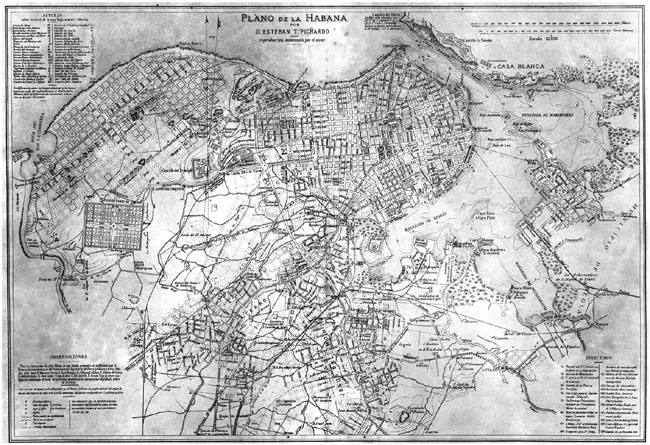

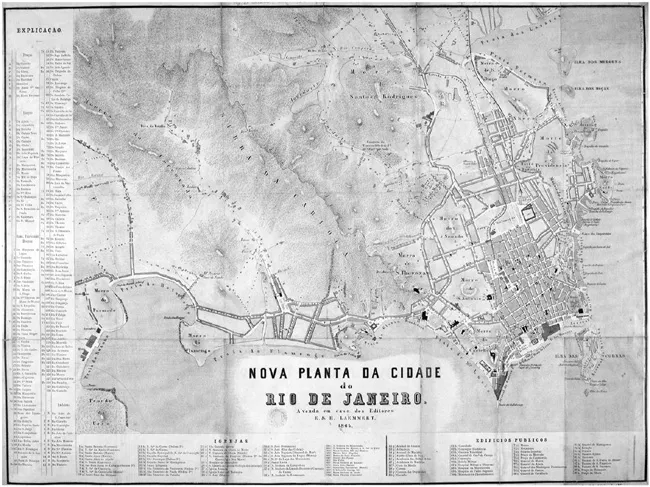

Neither Josepha Gonçalves de Moraes, in Rio de Janeiro, nor Ramona Oliva, in Havana, had been born in the city where her claim was filed. Yet for each woman, these “Atlantic port cities” were not merely the backdrop to her actions, but a significant part of her story, shaping her relationship to law and labor, slavery and freedom. In turn, such women would also influence the cities in which they arrived. They joined the vast ebb and flow of humanity that made Havana and Rio de Janeiro fast-growing, cosmopolitan places, crowded with newcomers from far-flung provinces and from across the seas. Women of color were part of each city’s visual landscape, vividly depicted by foreign visitors as they walked the streets selling foodstuffs or gathered at water fountains to wash clothes and chat in many tongues.1 In the 1870s and 1880s, as Brazil and Cuba each witnessed sweeping political, economic, legal, and social change leading eventually to abolition, the long road from enslavement to freedom led through the cities of Rio de Janeiro and Havana.

Havana, 1881. Esteban T. Pichardo, “Plano de la Habana,” 1881. Archivo de la Oficina del Historiador de la Ciudad, Havana.

Rio de Janeiro, 1864. E & H Laemmert, “Nova Planta da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro,” 1864. The British Library Board.

URBAN SLAVERY IN HAVANA AND RIO DE JANEIRO

The first and often most abiding image that greeted most travelers arriving in each city was that of the docks. Generations of visitors described bustling, lively scenes of slave porters carrying luggage and cargo, streams of passengers disembarking from across the world, and the cries of vendors peddling their wares.2 The docks, from which goods were exported for European and North American consumption, provided the crucial link between the wealth and prestige of these Atlantic cities and the rural, plantation economies on which each country’s fortunes were built. Among the many goods shipped across the world from each port, one in particular marked each city’s nineteenth-century “second slavery” story: sugar in Cuba, and coffee in Brazil. Produced through the sweat and toil of countless enslaved plantation laborers, each product’s growth was partly stimulated by the very abolition of the slave trade and then slavery itself in other American territories.3

In Cuba, sugar plantations fanned out from Havana province from the late eighteenth century. The region’s population quadrupled between 1777 and 1817 as towns close to the capital that functioned as sugar and tobacco outposts—San Antonio de los Baños, Güines, Guanajay, Jaruco—mushroomed.4 Sugar exports grew staggeringly by the mid-nineteenth century, almost doubling between 1841 and 1859.5 By the mid-1850s, Havana’s docks were officially among the busiest in the world.6 As the lands around Havana became gradually exhausted, the sugar frontier expanded eastwards, to Matanzas and Cienfuegos.7 Nonetheless, Havana province still contained 130 sugar estates in 1862, worked by 19,404 slaves.8

In Brazil, meanwhile, coffee plantations gradually conquered the southeastern provinces of Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro, spreading west and south along the Paraíba valley. The middle of the nineteenth century was the heyday of Vassouras, a coffee town in the province of Rio de Janeiro that became flooded with the wealth of the plantations and maintained close links to the imperial capital.9 As with sugar in Cuba, soil exhaustion and constant expansion of production meant that coffee had a moving frontier. By the 1870s and 1880s, the most thriving and modern plantations were to be found in São Paulo, where coffee boomed as prices almost doubled over the second half of the nineteenth century.10 National production doubled from 1850 to 1880 and would triple in the 1890s.11

It was in these rural worlds where the fortunes were made that helped transform Havana and Rio de Janeiro into two of the Americas’ largest and wealthiest nineteenth-century metropolises. The connections between each city and its rural surroundings were intimate and quotidian. Successful planters used their wealth to construct elegant city residences where they spent much of the year. Coffee and sugar stimulated a raft of urban sectors, from banking and insurance to commerce and shipbuilding. Meanwhile, even as they were fed by imports of dried beef from Rio Grande do Sul to Rio de Janeiro, or exported boatloads of Cuban pineapples from Havana to New York, the cities’ expanding urban populations also consumed the produce of their rural hinterlands.12 On the cities’ outskirts, urban neighborhoods gradually petered out into small farms, often worked by enslaved or free people of color, who also acted as muleteers and cart-drivers, daily transporting goods but also news and information into and out of the cities.13 These rural fringes also harbored communities of fugitive slaves, who established furtive, symbiotic links of trade and communication with city residents.14 As well as these daily connections, the rural context also played an important symbolic role in urban life. Even for slaves who had lived their whole lives in the city, the threat of sale to plantation labor was always in the back of their minds, and it was used by owners to maintain obedience and to discipline transgressors.

Intimately linked to the surrounding countryside, Havana and Rio nonetheless each had a long tradition of specifically urban slavery.15 Slaves made up a staggering one-half of Rio de Janeiro’s growing population for much of the first half of the nineteenth century.16 The end of the African trade in 1850, manumission, and a significant drain of urban slaves to plantation labor meant that by the 1870s, as Josepha arrived in the city, the enslaved population had fallen considerably. Yet there were still almost 50,000 slaves in Rio by 1872—around one fifth of the city’s total population.17 Havana’s slaves never reached the proportions that Rio’s had done earlier in the century, but Havana had long contained significant numbers of enslaved people, who made up over a third of its population in 1791.18 Across the nineteenth century, while the city grew, the enslaved proportion of its population fell, reaching one fifth by 1846.19 By 1861, Havana contained 24,381 slaves, who comprised 14 percent of the city’s population of 179,996.20 As the “free womb” laws were introduced, then, the numbers of remaining slaves in each city had fallen from their peak but remained significant.

Exposed to poor living conditions, diets, and standards of hygiene, the lives of most urban slaves were harsh and short. They were pitifully vulnerable to disease and infant mortality.21 Their work was often physically exhausting, although most perceived it as preferable to the grueling labors of field slaves, who cut cane or picked coffee in the burning sun. They were subject to brutal physical punishments, carried out by owners or by urban authorities seeking to impose public discipline.22 And while slaves on large, stable plantations had a reasonable chance of forming families and communities away from the vigilant eyes of slaveholders, this was harder to achieve for domestic slaves, who most often lived in their owners’ households.23 Such conditions continued for many who managed to achieve freedom, since their poverty and lack of autonomy helped ex-owners to continue exercising seigneurial “rights” over them.

Despite all these hardships, Rio de Janeiro and Havana each held a compelling attraction for enslaved people. Just as the imaginary of the plantation shaped urban slave life, so slaves on distant plantations imagined cities they had never seen as places that offered greater access to autonomy and to the cash that might help them purchase freedom. In each city, for example, some slaves had long worked to earn a daily wage, a practice referred to in Cuba as earning jornal por su cuenta and in Brazil as trabalhar ao ganho.24 As long as the enslaved person paid the owner the required daily amount, the way they earned the money and how they used any surplus was up to them. Although only a minority earned jornal, urban slavery also presented other opportunities to earn money. While most slaves in Cuba and Brazil would not manage to buy freedom in their lifetime, relatively high manumission rates meant they often at least knew others who had done so, keeping alight a small flicker of hope of following in their footsteps.25 And as slaves knew, the chances of this were much higher in the cities than in the countryside.26

Beyond the distant hope of manumission, urban living offered some chances of greater daily autonomy, which was valuable in itself. Although prized domestic servants might be kept indoors, others were sent out to the street to perform errands, providing precious moments of social and leisure time, whether to chat with a neighbor or parente or to attend a dance, associational meeting, or religious festival.27 Other slaves spent almost all their time on the street.28 In Rio, some managed to rent private rooms to sleep away from owners’ houses.29

Both cities also housed large numbers of free people of color, often crowded into poorer areas.30 In Havana, they might live in solares (subdivided houses) in the fast-growing neighborhoods beyond the city walls. In Rio, the urban poor increasingly inhabited the rapidly expanding slum tenements known as estalagens or cortiços—this latter term meaning “beehives”—which, by the 1880s, jostled for space with wealthy residences and provoked fear and outrage among the city’s elites.31 Among the itinerant, amorphous urban population, it was difficult to tell slave from free. Urban fugitive slaves often avoided recapture for long periods, blending into what Sidney Chalhoub has termed the cidade esconderijo, or city hideout.32

Enslaved and free(d) people of color built a rich cultural and social life in the cities. Havana and Rio were home to important, longstanding religious brotherhoods—irmandades, cofradías, cabildos de nación—organized around African “nations,” or ethnic identities recast in the New World. Brotherhoods and other associations offered their members limited manumission funds, credit, and insurance and helped with the all-important business of dying, helping pay for a “good death” through the funeral rites that both marked the deceased’s social position and facilitated that person’s passage to the afterlife.33 Cities offered the best chances for such organizations to flourish, although their roots reached out into the rural peripheries and beyond, deep into the countryside.34 The cities reverberated with African-derived religious and cultur...