1

HOUSING

‘I will extend opportunities to people who never had them before. As you know, we are building a property-owning democracy.’

Margaret Thatcher, interviewed in Time magazine, 22 June 1987

‘Over the Parliament our aim is to increase home ownership by one million and in particular help young families struggling to be first-time buyers.’

Tony Blair, speech to the Labour party conference, 27 September 2005

Starting at the top: owning a home

For decades now, politicians have been spoon-feeding British voters the same comforting message: home ownership is good – it helps build a ‘stakeholder society’ as Blair said, or a ‘property-owning democracy’ as both Thatcher and Cameron put it. Just before he became prime minister, Gordon Brown went even further: ‘The problem is that even with the great ambitions of the 1950s or the 1980s, they did not succeed in widening the scope for home ownership to large numbers of people who want it’, he told reporters. ‘I would say a home-owning, asset-owning, wealth-owning democracy is what would be in the interests of our country because everybody would have a stake in the country.’1

Over the last 30 years there has been an observable change in the language, culture and attitudes of British people towards home-ownership, just as the politicians wanted. It’s no longer something people aspire to – they view owning their own bricks and mortar as a right. Home-owning is counted by government as the primary mechanism by which people can save money throughout their lifetime, and as the best way to bind people into their communities and create a stable environment for children.

That stability could also be attained through the rental sector, as it is on the continent, but, as we’ll see, the rules, regulations and costs that govern the rented sector have conspired to ensure that tenants are always second-class citizens in our property-owning democracy.

If you’re looking for some measure to show how intensely home-ownership has been hard-wired into Britain’s national psyche, just look at Britain’s prime-time TV slots, ‘dinner-party conversations’ and newspaper front pages. They are fascinated by it. It’s a national obsession, but not one in which our generation can be involved. We can’t afford it.

Part of the explanation we’ve received for being kept out of home-ownership is that Britain is in the middle of a ‘housing crisis’. We all know that. The phrase is so ubiquitous that in the last decade it has appeared twice each day on average in one national publication or another.2 We’re told that there are many reasons for this crisis – a shortage of land, the growth in the buy-to-let market, the failure to build enough homes, and property speculation that has forced up their price. And in the meantime the jilted generation – the young – just happen to be left out. ‘Hard luck. Sorry. Wait a few years and you’ll be fine’, everyone else might as well be saying.

If this ‘crisis’ forms one half of popular discussions about housing, the rest comes from the personal experience of Britain’s opinion-formers and commentators. And, no surprises here, it’s the jilted generation they have in their sights.

Scores of newspaper columnists have warned of the unhappy effect of ‘boomerang kids’ who return home to live with their parents after university on the household income. Others have exhorted parents to ‘do the responsible thing’ and ‘kick out the KIPPERS’ – ‘Kids In Parents’ Pockets Eroding Retirement Savings’.

We’re told that we’re freeloaders. And even acronyms created by sympathetic think-tanks to diagnose our problems in novel ways, like iPod – ‘Insecure, Pressurised, Overtaxed and Debt-ridden’ – are turned against us.

‘Were these iPods’, grumbled the columnist Giles Hattersley3 in a Times article entitled ‘The Indulged Generation’, ‘not the same lot who choose to study away from home, marry in their thirties and spend the decade their parents raised their children in, chasing dreams and drifting from career to career? How can it come as a surprise to any of them when they can’t afford a house?’ Concluding, Hattersley says that this peculiar acronym should be re-christened to reflect the true nature of our generation: ‘Infantile Posse of Over-indulged Drunks’.4

We’re told that all this is our fault. Our generation is seen as so feckless that there has even been a BBC2 programme, Bank of Mum and Dad, in which ‘grown-ups’ concerned about their children’s lifestyle performed the financial equivalent of an alcoholic’s intervention to attempt to put them on the straight and narrow.

And just in case we might wheedle our way out of such criticism by pretending our circumstances are different, pre-eminent scientists like Kenan Malik are only too happy to explain: ‘The idea that you [Britain’s young people] are uniquely disadvantaged seems to be absurd.’5

In the following pages, we’ll begin to present a rather different picture. We’ll explain what’s actually going on in the housing market, the facts behind how our parents’ generation got their own houses – facts that have been conveniently swept under the carpet like an embarrassing family secret – and we’ll try to pin down who and what is to blame for the disaster that is modern British housing.

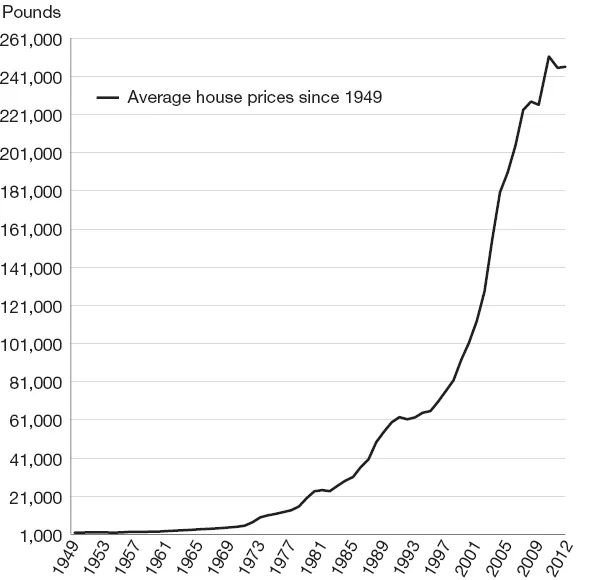

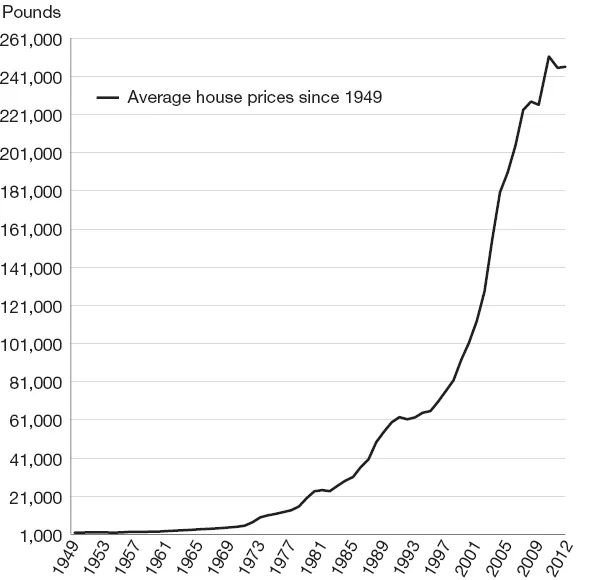

Let’s start with a no-brainer. Figure 3 shows that since 1949, house prices have, with the odd blip, risen fairly consistently. The graph isn’t in ‘real terms’, so it’s not adjusted for inflation (we’ll come to that). What it shows is that if you bought for £1,911 – the average house price – in 1949, that house would have risen in value to £2,530 by 1960, and in 1990 the same house would be worth £60,000. Today it would be £246,032.

Figure 3. Average house prices since 1949 (Department of Communities and Local Government (DCLG), table 502).

Gazing knowingly at these figures, perhaps the older generation can take some comfort that prices were cheaper twenty years before they bought their first house, just as they were cheaper in 1990 than now. They suffered the same trouble, they might argue. It’s always been tough. And they might have a point – earning enough to buy your own home is a real struggle. People make sacrifices to do it. Earlier generations sacrificed to buy knowing that a stable home would be a good investment for their savings and their family. Now we, they argue, must sacrifice too – and what’s more, we should quit whining about it like the ‘over-indulged drunks’ we are. But this graph masks the real facts.

Behind the curtains

If Britain’s political leaders wanted to create that ‘property-owning democracy’, then critical to the project was ensuring that young people could get into the housing market quickly. And, twenty years ago, that seemed to be working out OK. In 1990, if you went around Britain knocking at every home, you would discover that 8 per cent of the owners were under the age of 25, and that 43 per cent were aged between 25 and 34. Young people, in other words, accounted for more than half of all home-owners. Repeat the experience twenty years later and what you find is a remarkable change: just 2 per cent of home-owners are under 25, and 27 per cent are aged 25–34.6 And this change is far too large to be explained by demographics alone.

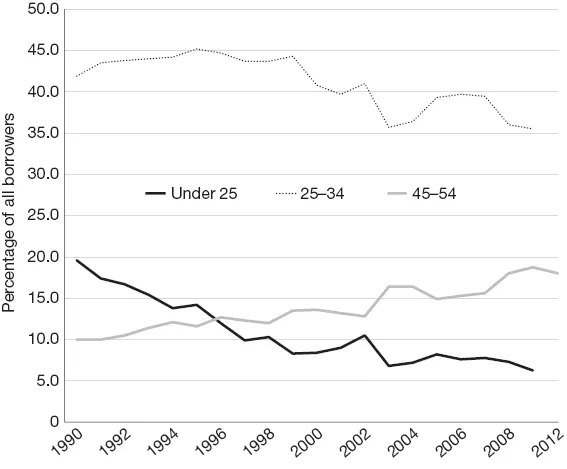

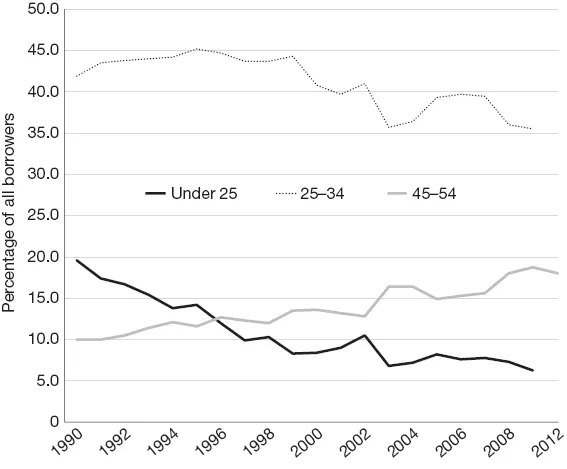

Now instead of going around to everyone’s house, imagine going around to every single bank and building society and asking them who they’ve been giving mortgages to in the last twenty years. Figure 4 measures the age of mortgage borrowers during the greatest era of easy credit in history. As you can see, despite outrageous 90, 100 and even 125 per cent mortgage offers, the proportion of young people with mortgages fell for both the under-25s and the 25–34 group, from around 62 per cent of total borrowers in 1990 to just under 45 per cent in 2012. Meanwhile, borrowers in the 45–54 age range have gone from making up 10 per cent of the mortgage market to 18.1 per cent.

Figure 4. Mortgage borrowers by age, UK (DCLG, table 537).

If you narrow this picture of the total mortgage market right down to just those mortgages given out to first-time buyers, you can see a similar pattern. In 1990 under-25s made up 30 per cent of the first-time buyer market. By 2012, those first-timers made up just 15.7 per cent of the market. The rate halved. Meanwhile, in the demographic 25–34, there has been a gain in the number of buyers of around the same proportion. The facts are pretty conclusive: first-time buyers are buying later.

So why is this? The Council of Mortgage Lenders thinks it has something to do with lifestyle choices. ‘More young people going to university and trends towards later marriage and child-bearing, mean that people are delaying their house purchase decisions.’7

It’s a view sh...