![]()

1

Understanding Development: Theory and Practice into the Twenty-First Century

What is ‘development’? How did it become both so important and so problematic? In this introductory chapter we outline the history of development and its theoretical underpinnings, from its Enlightenment origins to the present before asking what became of ‘the postmodern challenge’? The chapter is broadly presented in two parts. The first half of the chapter spans the period up to 1996 when the first edition of this book was published. It introduces the ‘aid industry’, analyses the history of the idea of development, and discusses the rise and fall of its grand theories. In the second part, we discuss some of the wide-ranging changes that have taken place during the past two decades, both within the world at large, where the balance of global power has shifted in significant ways, inequalities both within and between nations have increased, and where there has been a post 9/11 policy emphasis on securitisation; and also within the world of development. This has seen an increased and growing role for the private sector, an increased emphasis on managerialism and results in the development intervention field, and the rise of non-Western donor countries such as China that offer low-income countries new choices in relation to aid and projects.

Development: history and meanings

In virtually all its usages, development implies positive change or progress. It also evokes natural metaphors of organic growth and evolution. The Oxford Dictionary of Current English defines it as ‘stage of growth or advancement’ (1988: 200). As a verb it refers to activities required to bring these changes about, while as an adjective it is inherently judgemental, for it involves a standard against which things are compared. While ‘they’ are undeveloped, or in the process of being developed, we (it is implied) have already reached that coveted state. When the term was used by President Truman in a speech in 1949, vast areas of the world were therefore suddenly labelled ‘underdeveloped’ (Esteva, 1993: 7). A new problem was created, and with it the solutions; all of which depended upon the rational-scientific knowledge of the so-called developed powers (Hobart, 1993: 2).

Capitalism and colonialism: 1700–1949

The notion of development goes back further than 1949, however. Larrain has argued that while there has always been economic and social change throughout history, consciousness of ‘progress’, and the belief that this should be promoted, arose only within specific historical circumstances in northern Europe. Such ideas were first generated during what he terms the ‘age of competitive capitalism’ (1700–1860): an era of radical social and political struggles in which feudalism was increasingly undermined (Larrain, 1989: 1).

Concurrent with the profound economic and political changes that characterised these years was the emergence of what is often referred to as the ‘Enlightenment’. This social and cultural movement, which was arguably to dominate Western thought until the late twentieth century, stressed tolerance, reason and common sense. These sentiments were accompanied by the rise of technology and science, which were heralded as ushering in a new age of rationality and enlightenment for humankind, as opposed to what were now increasingly viewed as the superstitious and ignorant ‘Dark Ages’. Rational knowledge, based on empirical information, was deemed to be the way forward (Jordanova, 1980: 45). During this era polarities between ‘primitive’ and ‘civilised’, ‘backward’ and ‘advanced’, ‘superstitious’ and ‘scientific’, ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ became commonplace (Bloch and Bloch, 1980: 27). Such dichotomies have their contemporary equivalents in notions of undeveloped and developed.

Larrain links particular types of development theory with different phases in capitalism. While the period 1700–1860 was characterised by the classical political economy of Smith and Ricardo and the historical materialism of Marx and Engels, the age of imperialism (1860–1945) spawned neo-classical political economy and classical theories of imperialism. Meanwhile, the subsequent expansionary age of late capitalism (1945–66) was marked by theories of modernisation, and by the crises of 1966–80 by neo-Marxist theories of unequal exchange and dependency (Larrain, 1989: 4). We shall elaborate on these later theories further on in this chapter.

While capitalist expansion and crisis are clearly crucial to the history of development theory, the latter is also related to rapid leaps in scientific knowledge and social theory over the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A key moment in this was the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859. This was to have a huge influence on the social and political sciences in the West. Inspired by Darwin’s arguments about the evolution of biological species, many political economists now theorised social change in similar terms. In The Division of Labour (1947, originally published in 1893), for instance, Emile Durkheim – who is now widely considered one of the founding fathers of sociology – compared ‘primitive’ and ‘modern’ society, basing his models on organic analogies. The former, he suggested, is characterised by ‘mechanical solidarity’, in which there is a low division of labour, a segmentary structure and strong collective consciousness. In contrast, modern societies exhibit ‘organic solidarity’. This involves a greater interdependence between component parts and a highly specialised division of labour: production involves many different tasks, performed by different people; social structure is differentiated, and there is a high level of individual consciousness.

Although their work was quite different from Durkheim’s, Marx and Engels also acknowledged a debt to Darwin (Giddens, 1971: 66). Marx argued that societies were transformed through changes in the mode of production. This was assumed to evolve in a series of stages, or modes of production, which Marx believed all societies would eventually pass through. Nineteenth-century Britain, for example, had already experienced the transformation from a feudal to a capitalist mode of production. When capitalism was sufficiently developed, Marx argued, the system would break down and the next stage – of socialism – would be reached. We shall discuss below the influence of Marxism on theories of development.

Closely associated with the history of capitalism is of course that of colonialism. Particularly over later colonial periods (say, 1850–1950), notions of progress and enlightenment were key to colonial discourses, where the ‘natives’ were constructed as backward or childlike, and the colonisers as rational agents of progress (Said, 1978: 40). Thus while economic gain was the driving force for imperial conquest, colonial rule in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries also involved attempts to change local society with the introduction of European-style education, Christianity, and new political and bureaucratic systems. Notions of moral duty were central to this, often expressed in terms of the relationship between a trustee and a minor (Mair, 1984: 2). While rarely phrased in such racist terms, development discourse in the 1990s often involves similar themes: ‘good government’, institution building and gender training are just three currently fashionable concerns which promote ‘desirable’ social and political change. With these concepts arising from such dubious beginnings, it is hardly surprising that many people today regard them with suspicion.

By the early twentieth century the relationship between colonial practice, planned change and welfarism had become more direct. In 1939, for example, the British government changed its Law of Development of the Colonies to the Law of Development and Welfare of the Colonies, insisting that the colonial power should maintain a minimum level of health, education and nutrition for its subjects. Colonial authorities were now to be responsible for the economic development of a conquered territory, as well as the wellbeing of its inhabitants (Esteva, 1993: 10).

The postcolonial era: 1949 onwards

Notions of development are clearly linked to the history of capitalism, colonialism and the emergence of particular European epistemologies from the eighteenth century onwards. In the latter part of the twentieth century, however, the term has taken on a range of specific, although often contested, meanings. Arturo Escobar (1988, 1995) argues that it has become a discourse: a particular mode of thinking, and a source of practice designed to instil in ‘underdeveloped’ countries the desire to strive towards industrial and economic growth. It has also become professionalised, with a range of concepts, categories and techniques through which the generation and diffusion of particular forms of knowledge are organised, managed and controlled (Escobar, 1995). We shall be returning to Escobar’s views of development as a form of discourse, and thus of power, later on in this book. For now, let us examine what these more contemporary post-Second World War meanings of development involved.

When President Truman referred in 1949 to his ‘bold new programme for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas’ (cited in Esteva, 1993: 6), he was keen to distance his project from old-style imperialism. Instead, this new project was located in terms of economic growth and modernity. Countries, it was assumed, would be able to move through a set of stages of economic growth during which the constraints of traditional forms of social organisation would give way to the modern values of individualism and innovation that would allow capitalist economic development to flourish. During one of the earliest missions of the newly formed International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) to Colombia in 1949, for example, it was integrated strategies to improve and reform the economy that were called for, rather than the consideration of social or political changes. The definition of development as economic growth has remained central to mainstream thinking ever since, through the debt crises of the 1980s and the subsequent imposition on poor countries of ‘structural adjustment’ programmes by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the 1990s good governance policy agendas. Despite the challenge from some sections of the UN in the form of the idea of ‘human development’ that was put forward by Mahbub ul Haq and Amartya Sen, and the rise of ‘poverty reduction’ as a mainstream development objective during this period, the idea of development as economic growth never really went away. It returned to high prominence once again in the 2000s in studies such as Dollar and Kraay’s (2002) influential study Growth Is Good for the Poor, which became one of the World Bank’s most widely cited publications (de Haan, 2009).

Behind these aims is the assumption that growth involves technological sophistication, urbanisation, high levels of consumption and a range of social and cultural changes. For many governments and experts the route to this state was industrialisation. As we shall shortly see, this is closely linked to theories of modernisation. Successful development is measured by economic indices such as the Gross National Product (GNP) or per capita income. It is usually assumed that this will automatically lead to positive changes in other indices, such as rates of infant mortality, illiteracy, malnourishment and so on. Even if not everyone benefits directly from growth, the ‘trickle-down effect’ will ensure that the riches of those at the top of the economic scale will eventually benefit the rest of society through increased production and thus employment. In this understanding of development, if people become better fed, better educated, better housed and healthier, this is the indirect result of policies aimed at stimulating higher rates of productivity and consumption, rather than of policies directly tackling the problems of poverty. Development is quantifiable, and reducible to economics. One major drawback to defining development as economic growth is that in reality the ‘trickle-down effect’ rarely takes place; growth does not necessarily lead to enhanced standards of living. As societies in the affluent North demonstrate, the increased use of highly sophisticated technology or a fast-growing GNP does not necessarily eradicate poverty, illiteracy or homelessness, although it may well alter the ways these ills are experienced. In contrast, neo-Marxist theory, which was increasingly to dominate academic debates surrounding development in the 1970s, understands capitalism as inherently inegalitarian. Economic growth thus by definition means that some parts of the world, and some social groups, are actively underdeveloped. Viewed in these terms, development is an essentially political process; when we talk of ‘underdevelopment’ we are referring to unequal global power relations.

Although the modernisation paradigm continued to dominate mainstream thought, this definition of development – as resulting from macro and micro inequality – was increasingly promoted during the 1970s and, within some quarters, throughout the 1980s. It can be linked to what became termed the ‘basic needs’ movement, which stressed the importance of combating poverty rather than promoting industrialisation and modernisation. Development work, it was argued, should aim first and foremost at satisfying people’s basic needs; it should be poverty-focused. For some, this did not involve challenging wider notions of the ultimate importance of economic growth, but instead involved an amended agenda in which vulnerable groups such as ‘small farmers’ or ‘women-headed households’ were targeted for aid. Many of these projects were strongly welfare-oriented and did not challenge existing political structures (Mosley, 1987: 29–31).

In the 1990s the desirability of technological progress was further questioned. Environmental destruction in the form of deforestation, pollution and ozone depletion was an increasingly pressing issue and sustainability became an important development buzzword. By the 2000s climate change was also becoming a development issue, as studies by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) began to receive more attention (see Castro et al., 2012). Cases where technological change has been matched by growing inequality and the breakdown of traditional networks of support are now so well documented as to be standard reading on most undergraduate courses on development. It is becoming clear that mechanisation and industrialisation are mixed blessings, to say the least. Combined with this, the optimism of the 1960s and early 1970s, when many newly independent states were striving for rapid economic growth, was replaced by increasing pessimism during the 1980s. Faced by debt, the inequality of international trading relations and in many cases political insecurity, many governments, particularly those in Africa and Latin America were forced to accept the rigorous structural adjustment programmes insisted upon by the World Bank and IMF.

Development involved the construction not only of particular ideas, but also of a set of specific practices and institutions. Before turning to the various theories that have been offered since 1949 to explain development and underdevelopment, let us therefore briefly turn to what is often referred to as ‘the aid industry’.

The ‘aid industry’

As we have already indicated, aid from the North to the South was without doubt a continuation of colonial relations, rather than a radical break from them (Mosley, 1987: 21). Donors today tend to give most aid to countries which they previously colonised: British aid is concentrated mostly upon South Asia and Africa, while the Dutch are heavily involved in South East Asia, for example. Although planning is a basic human activity, the roots of planned development were planted during colonial times, through the establishment of bodies such as the Empire Marketing Board in 1926 and the setting up of Development Boards in colonies such as Uganda (Robertson, 1984: 16). The concept of aid transfers being made for the sake of development first appeared in the 1930s, however. Notions of mutual benefit, still prevalent today, were key. The aim was primarily to stimulate markets in the colonies, thus boosting the economy at home (Mosley, 1987: 21).

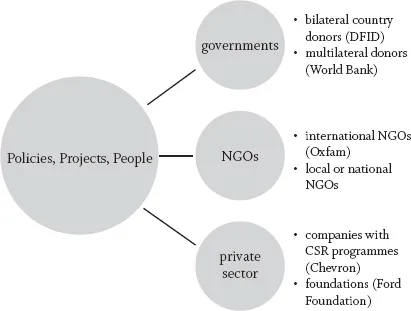

Despite these initial beginnings, the real start of the main processes of aid transfer is usually taken to be the end of the Second World War, when the major multilateral agencies were established. The IMF and the IBRD (later to become the World Bank) were set up during the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, while the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) was created as a branch of the United Nations in 1945. In contrast to what became known as ‘bilateral aid’, which was a transfer from one government to another, ‘multilateral aid’ came to involve a number of different donors acting in combination, none of whom (supposedly) directly controls policy. However, from the outset donors such as the World Bank were heavily influenced by the US and tended to encourage centralised, democratic governments with a strong bias towards the free market (Robertson, 1984: 23). Meanwhile, various bilateral agencies were also established by the wealthier nations. These are the governmental organisations, such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID; set up in 1961) or the British Department for International Development (DFID; previously the Overseas Development Agency [ODA], established as the Overseas Development Ministry in 1964), both of which are involved in project and programme aid with partner countries. Figure 1.1 shows the different main organisational actor types in the aid system.

Figure 1.1Agencies in the aid system

Considerable amounts of aid were initially directed at areas in Europe which were devastated after the Second World War. By the early 1950s the Cold War made aid politically attractive for governments anxious to stem the flow of communism in the South. During this period the World Bank changed its focus from reconstruction to development. By the late 1960s, after many previously French and British colonies had gained independence, aid programmes expanded rapidly. Indeed, rich donor countries actually began to come into competition with each other in their efforts to provide assistance to poor countries, a clear sign of the economic and political benefits which accompanied aid. Keen to improve their product, many now stressed development, instigating grandiose and prestigious schemes. The 1960s also saw the first UN Decade for Development, with a stated aim of achieving 5 per cent growth rates, and 0.7 per cent of donor countries’ GNP being given in aid. In 1984/5 the US gave 0.24 per cent, the UK 0.34 per cent, and Norway 1.04 per cent (Cassen et al., 1986: 8). Today few countries give this much, at least in per capita terms, with Scandinavian countries the most generous. In the UK, successive governments in recent years have aimed to raise aid spending in order to meet the 0.7 target which was finally achieved in 2014, though by this time many were questioning the relevance of such targets.1

Since the earliest days of the aid industry, there have been significant shifts in those countries giving and receiving the most aid. Sub-Saharan Africa receives the largest proportion o...