![]()

1

SCHOOLS AS SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

The words “education” and “schooling” are sometimes used interchangeably, but they are not the same. Education, learning about the particular ways of a group, occurs willy-nilly throughout life at home, in peer play, at religious ceremonies, at work. These informal processes of learning occur in every distinct social group. Young Ponapean Islanders in the South Pacific, for example, learn from parents or neighbors that the quietness of a man is like the fierceness of a barracuda, and they also learn how to shape bark to make a watertight canoe. American children also learn most of the things that equip them to survive in their society—from how to act if approached by a stranger to how to operate kitchen appliances—from the people around them in the course of daily life. The same is true of important parts of education in every group and every society: much of what individuals find necessary to learn for survival and acceptance is taught outside schools.

As the title Schools and Societies suggests, this book is not about education. Instead, it is about schooling, which is the more organized form of education that takes place in schools, and about the consequences of this organized form of education for individuals and for societies. Although schooling is in some ways more limited than education, it has great influence on the members of society. We are on strong ground to limit our scope to the study of schooling, because so much organized social effort goes into the formal education found in schools. It is also much easier to compare what happens in schools in different countries than it is to discuss the truly inexhaustible subject of what happens in educational processes generally.

A related distinction is the one between two academic disciplines: the philosophy of education and the sociology of schooling. The philosophy of education concerns itself primarily with how education ought to be organized and the ends that it ought to serve. Sociology concerns itself with what schools are actually like, with why schools are the way they are, and with the consequences of what happens in schools.

In making this distinction, I do not intend to imply a criticism of philosophy. Asking good questions about what schooling ought ideally to be can make existing forms of social life more visible and clear. For example, the philosopher’s idea that liberal education ought to provide a way of experiencing universal themes, such as the qualities of mature judgment, provides a good vantage point for sociological investigations about how changing national interests and cultural traditions shape humanities curricula. Both modes of thought have a legitimate place in the universe of academic study, but sociology is primarily concerned with what actually exists and how it came to be.

Mark Twain’s Education on the Mississippi

In Life on the Mississippi, the American writer Mark Twain provides a memorable reminiscence of his apprenticeship to a veteran Mississippi riverboat captain, a Mr. Bixby. Twain’s portrait reminds us of the difficulty of learning hard subjects and of what is gained and lost in the educational process. It also raises good sociological questions: Why are so few teachers as effective as Mr. Bixby? And why have schools displaced on-the-job apprenticeships in so many fields?

Like many adventurous boys in the 1830s, young Sam Clemens (Twain’s given name) longed to pilot one of the magnificent steamboats that carried the vast assembly of humanity, from roustabouts to fine ladies, and their cargo up and down the great Mississippi. Clemens apprenticed himself to Mr. Bixby in return for $500, to be paid out of his first wages as a pilot. Twain recalls the easy confidence with which he began his ordeal of learning the river. “I supposed that all a pilot had to do was keep his boat in the river, and I did not consider that could be much of a trick, since it was so wide” (Twain [1896] 1972: 31).

This easy confidence did not last the morning. Bixby began his lessons by pointing out some landmarks on the river where the water changed depth.

Presently he turned on me and said: “What’s the name of the first point above New Orleans?”

I was gratified to be able to answer promptly, and I did. I said I didn’t know.

“Don’t know? Well, you’re a smart one!” said Mr. Bixby. “What’s the name of the next point?”

Once more I didn’t know.

“Well, this beats anything. Tell me the name of any point or place I told you.”

I studied for a while and decided that I couldn’t. . . .

“You—you—don’t know?” mimicking my drawling manner of speech. “What do you know?”

“I—I—nothing, for certain.”

“By the great Caesar’s ghost, I believe you! You’re the stupidest dunderhead I ever saw or ever heard of, so help me Moses! The idea of you being a pilot—you! Why, you don’t know enough to pilot a cow down the lane.” (Twain [1896] 1972: 48–49)

Thus begins the education of the young Mark Twain on the Mississippi River. Soon Clemens’s notebook “fairly bristles” with the names of towns, points, bars, islands, bends, and reaches on the river, for the only way to get to be a pilot is to “get . . . [the] entire river by heart” (Twain [1896] 1972: 48). When he has finally completes his apprenticeship on the river, Twain reflects on what he has gained and lost in the effort:

Now when I had mastered the language of this water and had come to know every trifling feature that bordered the great river as familiarly as I knew the letters of the alphabet, I had made a valuable acquisition. But I had lost something, too. . . . All the grace, the beauty, the poetry had gone out of the majestic river! . . . A day came when I began to cease from noting the glories and the charms which the moon and the sun and the twilight wrought upon the river’s face; another day came when I ceased altogether to note them. . . . All the value any feature of it had for me now was the amount of usefulness it could furnish toward compassing the safe piloting of a steamboat. (49)

THE SOCIETAL IMPORTANCE OF SCHOOLING

Schooling is very highly valued by governments and their citizens. One indicator is that schooling takes up a large amount of young people’s time. If we assume that the average young person spends 6 hours in school 5 days a week and 9 months a year for at least 12 years, the total number of hours in school between the ages of 6 and 18 is almost 13,000. For the increasing number of people who complete a college degree, that figure climbs to over 17,000 hours of schooling. People who graduate from college will have spent, on average, 1 out of 6 of their waking hours in school from their 6th through their 21st year—and that does not count homework!

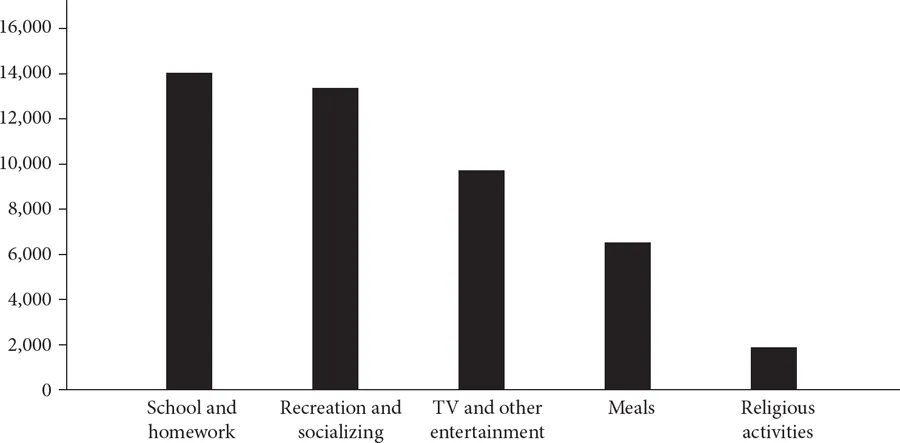

As Figure 1.1 shows, children spend more time in school than they do watching television and playing with friends during the course of an average week. Moreover, schools are more important as socializing agents for most children, given the amount of attention school requires and the highly involving competitions and group interactions that occur there. Judging simply in terms of the amount of time they take up, schools are also substantially more important than other community socializing institutions, such as churches and recreational activities (see Figure 1.1). Even those who attend two hours of religious services every week, for example, spend only approximately one-seventh the time in their churches, synagogues, or mosques between the ages of 6 and 18 that they do in their schools.

Another indicator of the importance that modern societies place on schooling is the amount of money they are willing to spend on it. Indeed, the most fundamental thing to be said about schooling in the contemporary world is that it involves substantial expenditure. Citizens devote relatively large amounts of their hard-earned money to build schools, maintain school grounds, purchase equipment and materials, and pay the salaries of teachers and staffs.

In the United States, expenditures on schooling from kindergarten to college account for approximately 7 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). More than $1 trillion is spent on education each year in the United States (OECD 2014: 222). This amount is not nearly as high as health care’s contribution to GDP, but it is about twice as much as the construction industry’s share of the GDP and more than five times the share of either the food-products or auto industry (U.S. Department of Commerce 2016).

Figure 1.1 Approximate total number of hours spent on various activities for an average American child from age 6 to 18

NOTE: School and homework calculated as 6 hours of school and 1 hour of homework per school day. Recreation and socializing calculated as 2.5 hours per day during the school year and 6.5 hours per day during summer vacation. Internet, television, and other entertainment calculated as 2.5 hours per day. Meals calculated as 1.5 hours per day. Religious activities calculated as 2 hours per week (churchgoers only).

Another good measure of a society’s commitment to schooling is the number of people working in schools. School teaching is by far the largest occupation classified as professional by the U.S. Census Bureau, numbering more than 4 million in 2014. College instructors and professors accounted for another 1.5 million, pushing the total number of teachers in the United States well past 5 million. Another 440,000 people worked in educational administration. The United States now has nearly three schoolteachers for every engineer, more than six teachers for every physician, and approximately seven teachers for every lawyer (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015b).

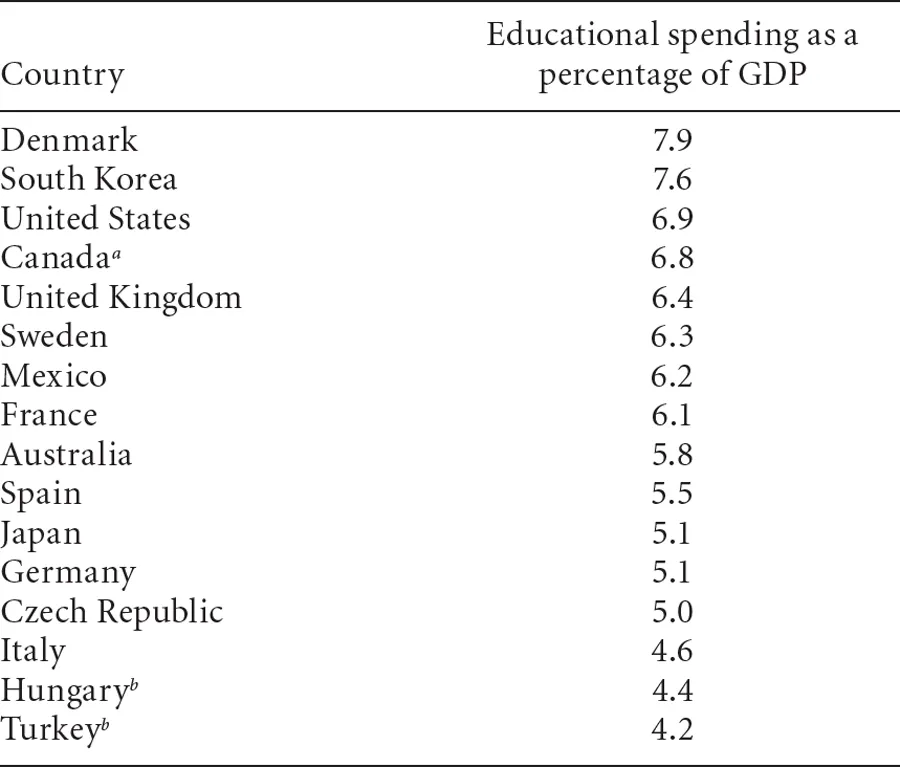

Expenditures on schooling are similarly high throughout the developed world. As Table 1.1 indicates, in the richer industrial societies spending on education at all levels typically accounts for between 4 and 8 percent of the GDP. The United States is on the high side (along with South Korea, New Zealand, Israel, Canada, and several Scandinavian countries); Japan, Germany, Italy, and several Eastern European countries are on the low side (OECD 2014: 222). People in developing countries may place even more faith in schooling as a road to economic and social progress, but they have fewer resources to devote to it. In developing countries, expenditures on schooling typically average between 2 and 3 percent of GDP. But they sometimes reach up to one-fifth or more of the government’s total budget (Kurian 2001; World Bank 2016a).

Why does virtually every country on the planet want to invest such large amounts of money in schooling? The answer is complex. Schooling was at one time limited to an elite, no more than the top 2 or 3 percent of the population, and it was run by private academies or by church officials. In Europe, the shift to schooling for the masses began in the late 1700s, led by kings who wanted to build a stronger loyalty to the state among poorer populations, particularly those living in the hinterlands (Bendix 1968: 243–48). In the United States, the shift to mass schooling began a short time later, in the early 1800s, and was linked to both the republican virtue tradition of some of the country’s earliest political leaders and the evangelical enthusiasm for building a strong moral and cultural base for a new democracy. Of course, teaching basic literacy and numeracy were principal goals, but it would be a serious mistake to downplay the role of schools as agents of morality. In the 19th century, schools became linked to the effort of the Protestant mainstream to Americanize new immigrants. In a heterogeneous society, composed of many ethnic and religious groups, schools were the closest approximation to an American established church. They taught Protestant-entrepreneurial values—such as temperance and industriousness—that were generalized into a creed as “the American way of life” (Berthoft 1971: 438).

TABLE 1.1

Educational expenditures as a percentage of GDP, selected countries, 2011

SOURCE: OECD 2014: 230.

a Year of reference is 2010.

b Public expenditure only.

Today, schooling is often thought to be an all-purpose panacea. More and better education is seen as the best solution to the common problems that ail most societies. Does a society have too many poor people? Does it have an epidemic of drug use? Does it have too many children who suffer at the hands of abusive parents? The first solution that many people think of is to try to change attitudes and behaviors through more and better education in public schools (see, for example, Graham 1993).

Most important, schooling has become strongly associated with interests of the nation-state in the development of a productive workforce and well-disciplined citizenry. Most people believe that education is the route to a better life, and they have good reason to believe it. Those who obtain baccalaureate degrees earn considerably more on average than those who finish only secondary school; in the United States on average the difference amounts to more than a million dollars over the course of a lifetime (Carnevale, Rose, and Cheah 2011). The net gains remain substantial even after subtracting forgone earnings while in college and the costs of obtaining a college education. Economists who study human capital (that is, the productive skills and experience of human beings) argue that improved education contributes to not only the economic value of individuals but also a country’s overall prosperity. Some have attempted to quantify the economic value of education, arguing that an increase of one year in the average education of a population is associated with an increase of between 3 and 6 percent of total economic output (OECD 2006: 152).

These kinds of calculations do not account for the technological, legal, and other institutional factors that are associated with a country’s level of economic prosperity. For this reason, the public benefit of education is more often calculated now solely in relation to state finances—that is, in relation to the higher taxes educated people pay and the lesser likelihood that they will require social services provided by the state, such as unemployment insurance. A recent report on countries in the developed world calculates that the public benefits for a man with higher education are on average 4 times as high as the public costs of education, and for a woman with higher education, 2.5 times as high (OECD 2014: 155).

Schooling seems to have other benefits as well. More highly educated people are healthier. They exercise more and are more attentive to diet. They read more books and newspapers than other people and are more likely to be informed about current events. They participate more actively in the political and civic life of their communities, are more cosmopolitan and tolerant in their social attitudes, and express higher levels of trust and happiness. What is more, educated people show these attributes, even when social backgrounds and current incomes are statistically controlled to isolate the effects of education alone (James Davis 1982; Hyman and Wright 1979; Kingston et al. 2003). Cognitive ability and preexisting dispositions may lie behind some of these education effects, but it is doubtful that they explain them all (Conti, Heckman, and Urzua 2010; Heckman et al. 2014; cf. Kingston 2015).

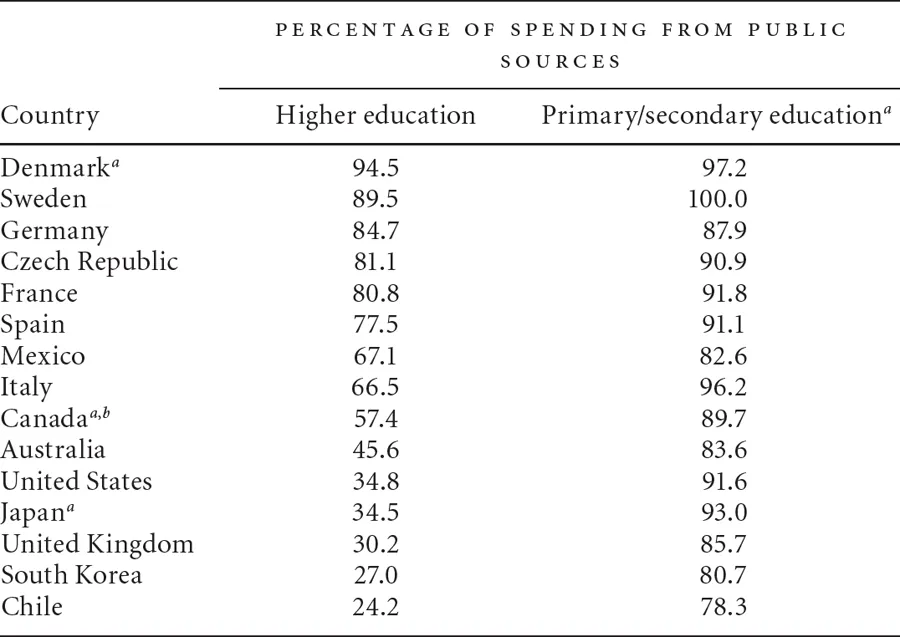

Elementary and secondary schooling is primarily an activity of the state. In the West, the state wrested control of education from churches in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is supported by taxes and provided free of charge to children. Some number of years of attendance is usually compulsory. This amount may vary from as few as 5 or 6 years in some developing countries to 10 or 11 years in most of the industrialized world. Indeed, although they were confronted by religious and ethnic opposition, nation-building states were able in the end to control the provision of primary and secondary schooling in every country but the Netherlands, where religious divisions prevailed. Today, primary and secondary schooling is primarily a publicly controlled activity in every country but the Netherlands (where financing, however, is public). The private sector is comparatively large in countries like South Korea and Japan, because of private supplemental schools that children attend after regular school.

TABLE 1.2

Relative proportion of public spending on educational institutions by level, selected countries, 2011

SOURCE: OECD 2014: 245.

a Some levels of education cross traditional boundaries between secondary and postsecondary education.

b Year of reference is 2010.

Higher education is a different matter. Here public and private alternatives very often coexist. South Korea, the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Australia have quite high private expenditures for college- and university-level education—half or more of all spending in these countries is private. Most of this spending comes in the form of tuition fees. By contrast, low tuition fees have remained a distinctive feature of Western European countries, even during the current period of enthusiasm for market-oriented public policies. Austria, Germany, and most Scandinavian societies provide higher education almost exclusively through public institutions and public funding (OECD 2014: 230). Table 1.2 shows the proportion of public funding relative to private funding at all school levels for 15 developed countries.

Given the preponderance of governmental control of schooling today and the nearly universal attendance of young people through age 14, it is remarkable to think that education in Western Europe and the United States before the late 18th century was almost entirely private or church run. It is even more remarkable that formal schooling, even in the elementary and early secondary schoo...