![]()

THE FLOWERING PLANT

Let the season be autumn, and although for good reasons gardeners generally do not make a practice of systematic seed-saving, let it be supposed that this year all garden seeds which are available are to be collected. Spread out on their seed-trays, the fruits and seeds present striking diversity of appearance. Some of the fruits are dry, and are already opening and liberating their seeds. Others are fleshy and must be cut open or allowed to rot in the ground before their seeds can grow.

Yet whether the fruits be dry or succulent, whether they split open naturally when ripe or whether they do not, nearly all the seeds which the garden provides may be seen to be borne within a seed-vessel (see figs. 60 and 61), which if it opens at all does not open till the seeds are ripe. Even grains of maize, wheat, and other cereals and grasses, though they look like seeds, consist of seed-vessel as well as seed. If the development of such a grain, e.g. maize, be traced from the flower to the fruit stage it will be seen that the small rounded body, the ovule, which becomes the seed, is contained within an ovary—a delicate bag-like structure which is prolonged to form the style or tassel of the flower. As development proceeds the seed enlarges within the ovary and the seed-coats fuse with the ovary-wall; so that, although the greater part of the grain consists of seed and seed-coats, it also comprises the remains of the “seed-vessel”, and is therefore no exception to the rule that the seeds of most garden plants are borne and matured in a seed-vessel.

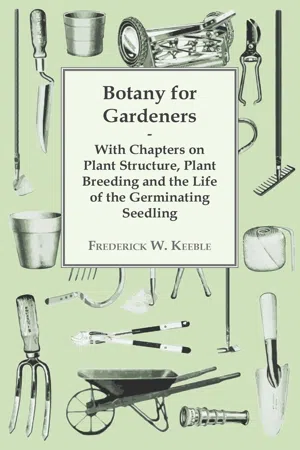

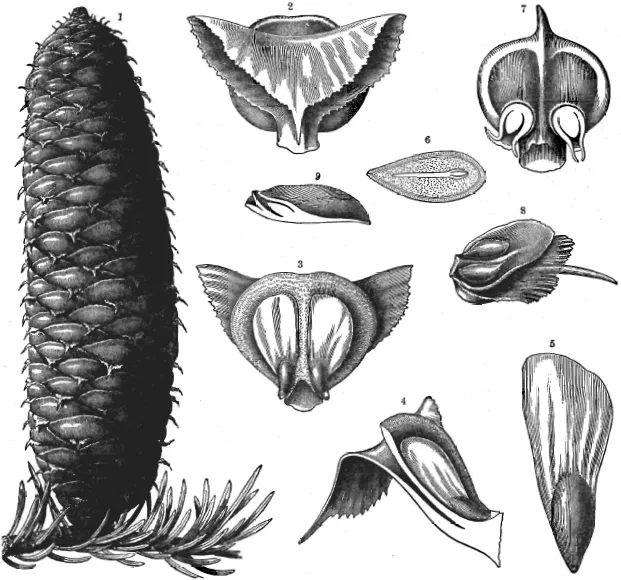

Fig. 60.—Structure of Angiosperm Ovaries

1, Dehisced fruit of Miltonia steilata. 2, Ovary of Miltonia cut across transversely. 3, Ovary of Mignonette (Reseda) cut across transversely. 4, The same ovary, intact. 5, Longitudinal section of the ovary of the Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus). 6, Ovary of the Violet (Viola odorata). 7, The same, cut across. 8, Receptacle and carpels of Myosurus minimus. 9, The same in longitudinal section. 10, Young fruit of Potato (Solanum tuberosum). 11, The same, cut transversely. All the figures considerably magnified.

There are, however, some seeds which are not produced within a closed seed-vessel. Those of the Yew, for example (see fig. 62, 1, 2, 3, 4), are borne direct on the ends of minute branches, and have begun to mature before the fleshy red extra coat or aril grows up from the base of the seed, and, enclosing it, gives the seed a berry-like appearance. So also with the seeds of Pines and Firs (figs. 62 and 63), which may be shaken out from the ripe woody cones: in Pines they lie in pairs (see fig. 63, 7) flat on woody plates, the ovuliferous scales, which in turn lie each on a bract- or cone-scale (cf. fig. 63, 4), and, although the cone itself is closed whilst the seeds are maturing, it presents not the slightest resemblance to the seed-vessel of a Poppy, Antirrhinum, Lily, or other ordinary garden plant. It is evident, therefore, that flowering plants fall into two groups which differ from one another in their method of seed-bearing. In the one, the seeds are formed and reach maturity in closed seed-vessels—dry pods or capsules, nuts or fleshy berries, &c. In the other they are borne not in closed vessels, but either on flat, open scales, like the winged seeds of the Pine, or in open scales as in Cypresses (fig. 64, 6), or quite nakedly as in Cycads (figs. 61, 62).

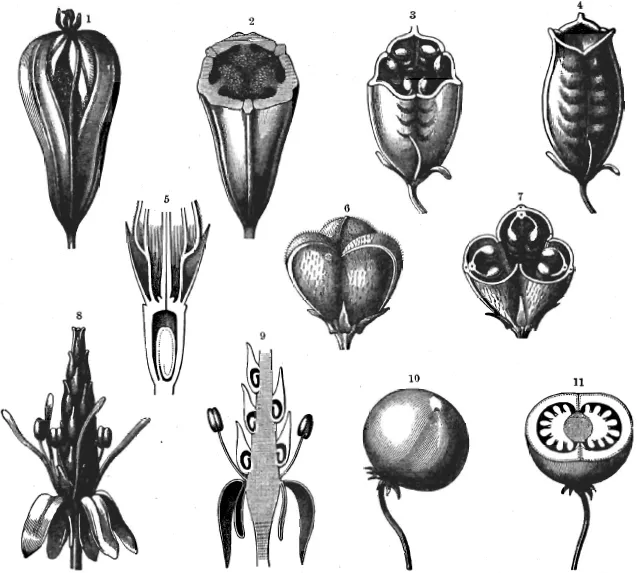

Fig. 61.—Structure of Angiosperm Ovaries

1, Excavated receptacle and carpels of a Rose (Rosa Schottiana). 2, The same in longitudinal section. 3, A single carpel of the same in longitudinal section. 4, Ovary of the Apple (Pyrus Malus) in longitudinal section. 5, The same in transverse section. 6, Transverse section of a ripe Apple. 7, Carpel of Cycas revoluta with ovules. 8, Longitudinal section of an ovule of Cycas. 1, 6, 7, 8, natural size; 2, 4, 5, × 3; 3, × 8.

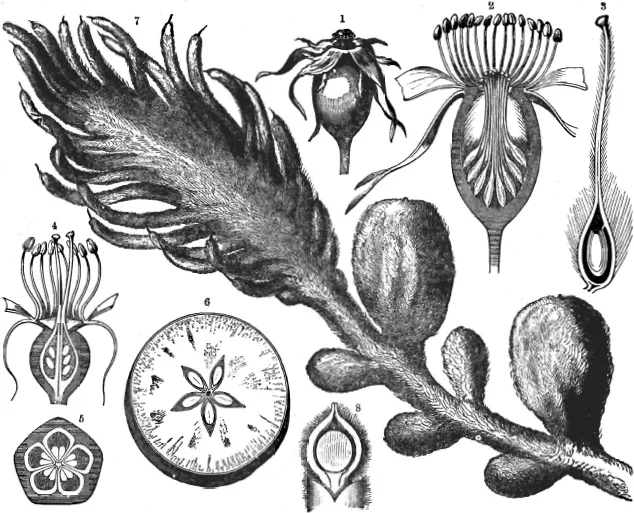

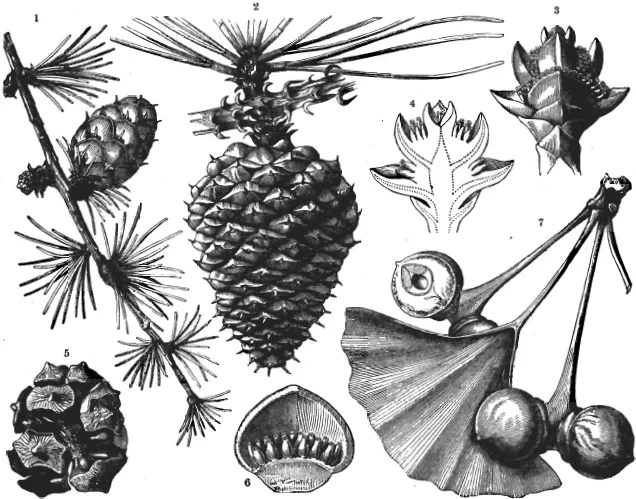

Fig. 62.—Fruits and Seeds of Coniferæ

1, Branch of Yew (Taxus baccata) with ripe seeds, each enclosed in its aril 2, Tip of ovule of same projecting from between the scales of the little fertile shoot. 3, Longitudinal section of the same. 4, Young seed of the same only partly enclosed in its aril. 5, Longitudinal section of the ripe seed of the same, showing the aril. 6, Branch of the Arbor Vitæ (Thuja orientalis) showing female flowers and ripe, burst cones. 7, Branch of Juniper (Juniperus communis) showing berry-like cones. 8, Longitudinal section of one of these cones. 9, Female flower of Juniper. 1, 6, and 7, natural size; the other figures enlarged.

The difference between these two modes of seed-bearing might seem but trivial and of no special interest to the gardener. To the botanist, on the other hand, it is of fundamental importance, as indicative of a final parting of the ways of plants which long ages ago, before botanists or even gardeners existed, were alike in their primitive method of seed-bearing. Of these plants some adopted as a new fashion the seed-vessel within which ovules were formed and grew into seeds, others failed to adopt this fashion. From the former sprang in the course of ages all the many thousand species of higher flowering plants; from the latter arose the relatively small numbers of conifers and allied naked-seed plants.

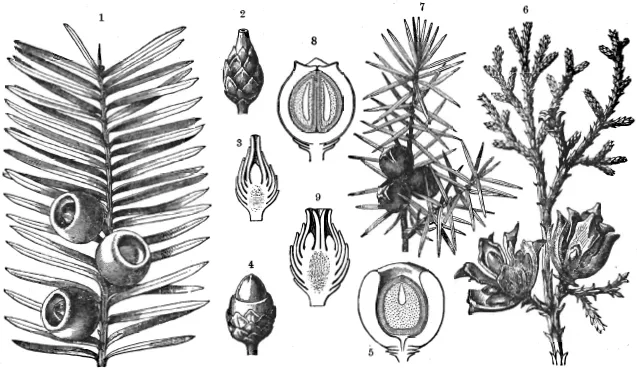

Fig. 63.—Fruit and Seed of Coniferæ

1, Cone of the Silver Fir (Abies pectinata). 2, Bract scale and ovuliferous scale of the same seen from the outside (the bract scale is pointed). 3, Ovuliferous scale of same seen from above, showing the two winged seeds, and the bract scale behind. 4, Longitudinal section of bract and ovuliferous scales, showing a seed inserted upon the latter. 5, A winged seed of the same. 6, Longitudinal section of the seed. 7, Ovuliferous scale of the Scotch Pine (Pinus sylvestris) seen from above. It bears two ovules. 8, Single ovuliferous scale of Larch (Larix europæa) showing two ovules on its surface and bract scale (with bristle) below it. 9, Longitudinal section of the ovuliferous scale of the Larch. 1, natural size, the other figs. enlarged.

Recognizing the fundamental significance of a true seed-vessel the botanist places all those seed-bearing plants which lack a seed-vessel in one class—the Gymnosperms(naked-seed plants), and all those which have a closed seed-vessel in another class, the Angiosperms (enclosed-sced plants). The former comprise the Cycads (see fig. 61), the Conifers, the curious Maiden - hair Tree (Ginkgo biloba; see fig. 64, 7), the solitary survivor in China of a once numerous, prosperous, and widely distributed family, and certain rare and isolated plants belonging to the family Gnetaceæ. However they may differ from one another in other respects all these plants agree in this, that they lack a closed seed-vessel. They may form fleshy or other investments around the ripening seed, e.g. Yew (fig. 62), and Ginkgo biloba (fig. 64); but the seed in its earlier stages of development, and the ovule from which the seed is produced, are not borne in a closed seed-vessel or ovary.

Fig. 64.—Coniferous Fruits and Seeds

1, Branch of the Larch (Larix Europæa) with ripe cone. 2, Branch of Pinus serotina with ripe cone. 3, Female flower of the Cypress. 4, Longitudinal section of the same. 5, Ripe cone of the Cypress (Cupressus sempervirens). 8, Single carpel of the Cypress with numerous ovules. 7, Branch of Ginkgo biloba with unripe fruit. 1, 2, 5, 7 natural size. The other figures enlarged.

The Angiosperms, on the other hand, all agree in producing ovules within an ovary, which after seed formation becomes the seed-vessel.

No one would readily believe that plants in which this method of seed production became a fixed habit had thereby laid the foundation of their supremacy in the world. Yet so it was: the marvellous and almost infinite variety of the higher flowering plants—which dominate the vegetation of the world, clothe the grasslands, form the woodlands, make the desert blossom, invade arctic and alpine regions, or adventure their lives in lakes and streams and sea—owe their world-empire to this small advance in organization and to the advantages which followed from its adoption. The assumption of the practice of producing and maturing seed within a closed vessel was not only important in itself. It also rendered possible the production of flowers of new and more efficient types, and the surer and thriftier begetting of offspring. Though it may not be possible to trace step by step the stages of the evolution of flowering plants, from those with inconspicuous flowers and unenclosed ovules and seeds to those which exhibit the fantastic complexity of the orchids, yet by comparing the flower of the Angiosperm with that of the Gymnosperm, and by studying some of the flowers of the commoner plants, it is possible to suggest the route along which the Angiosperms have made their triumphant way, jostling aside, though never shaking off altogether, the companionship of their lowlier fellows—the Conifers and their allies, and the Ferns and Mosses, the Algæ and Fungi, and the Bacteria.

The Flowers of Conifers.—The flowers of such a Conifer as the Mountain Pine (Pinus Pumilio) may serve as the starting-point of this inquiry; for although, as Conifers go, they show a remarkable and elaborate organization, the lines on which they are built are if not simpler yet less subtle than those of Angiospermous flowers.

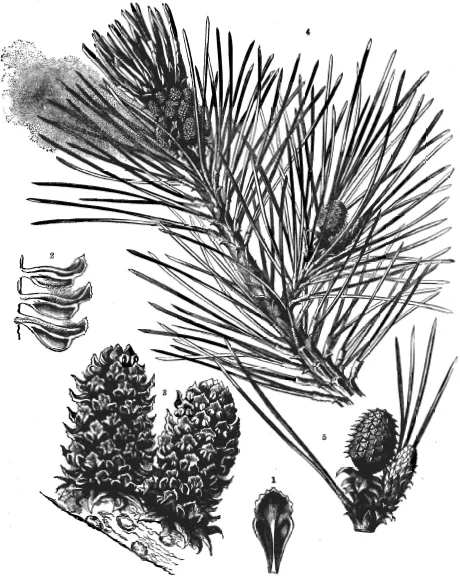

Fig. 65.—Mountain Pine (Pinus Pumilio)

1, A male sporophyll (stamen) seen from above. 2, Three male sporophylls, one above the other, seen from the side. The pollen falling from each anther alights on the upper surface of the stamen next below. 3, Two male cones. 4, Branch with apical group of staminal flowers from which pollen is being discharged. 5, Female cone. 1, 2, × 10; 3, × 8; 5, × 2; 4, natural size.

In the Mountain Pine the flowers are of two kinds, pollen-bearing or male, and ovule-bearing or female (see fig. 65). Each consists of a small cone-like structure, which is formed in the place of a side shoot. The male flower, which in the bud-stage is enclosed by scale-leaves, is composed of an axis bearing a succession of spirally placed, similar, leaf-like members or sporophylls. On the under side of each sporophyll are two oval pollen sacs (fig. 65, 2 and 3), which, when mature, split open and discharge a cloud of yellow, winged pollen. The female flower also consists of a short shoot or axis beset by spirally arranged sporophylls (the bract- or cone-scales, see fig. 65, 5). On the upper face of each bract-scale, as illustrated in fig. 63, 2-4, which represents the corresponding structure in the Silver Fir (Abies pectinata), is a pointed, flat, plate-like scale, the ovuliferous scale, which bears two ovules, each consisting of a somewhat ovoid mass of tissue—the ovule proper—with a coat or integument investing it, but open freely above (e.g. fig. 63, 7).

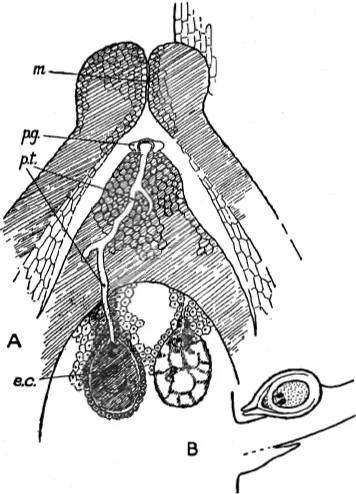

Fig. 66.—Fertilization in Pinus

A, Longitudinal section (highly magnified) of part of an ovule; m, Micropyle; p g., Germinated pollen grains; p.t., Pollen tube, the apex of which has reached the egg cell, e.c.B, Same, less highly magnified, showing the whole ovule in situ. Note integuments, micropyle, two egg cells, and ovuliferous scale.

In the mature cone the sporophylls have become woody, seeds have replaced the ovules, and portions of the ovuliferous scale have been carved out and split off to serve as a wing to each seed (cf. fig. 63, 5).

The flowers of Pines are wind-pollinated. The male flowers shed their pollen in such quantity that the air is heavy with it, and the female cone opens to receive it. Chinks appear between the cone-scales, and pollen grains, borne by the caprice of the wind, rarely fail to reach to the ovules (cf. fig. 66, A, p.g.). There the pollen lies dormant for a time. The chinks between the cone-scales close, and the ovules pursue the slow course of their development. When they are ready for fertilization the pollen-grains lying near them begin to grow. Each pollen-grain sends out a tube which grows into the tissue of the ovule. The pollen-tube reaches ultimately the neighbourhood of a large oval cell, the egg-cell or female gamete (fig. 66, A, e.C.). More than one egg-cell may be formed in an ovule, and toward each a pollen-tube may grow. Thus the pollen-grain is in fact an independent, albeit miniature and simply constructed, plant, which feeds like a parasite on the substance of the ovule. Its living contents divide to form several cells, two of which, consisting of minute, naked particles of living substance, ...