· CHAPTER ONE ·

The Literary Witness: Labyrinths in Pliny, Virgil, and Ovid

Dicamus et labyrinthos, vel portentosissimum humani inpendii opus, sed non, ut existimari potest, falsum.

We must speak also of the labyrinths, the most astonishing work of human riches, but not, as one might think, fictitious.

Pliny, Natural History 36.19.84

BY THE time of Juvenal (ca. 60–131 A.D.), “that thingummy in the Labyrinth” and “the flying carpenter” who built it were the stock in trade of hack poets, and references to the labyrinth and its associated myth abound in classical literature. Of the many writers who treated the subject, three are particularly important, not merely because of their stature in their own age but also because they defined the labyrinth for early Christian and medieval writers, establishing a rich storehouse of labyrinthine characteristics and associations and laying the groundwork for the literal and metaphorical mazes of later literature. These three classical authors are Virgil (70–19 B.C.), Ovid (43 B.C.–17 A.D.), and Pliny the Elder (23–79 A.D.), whom I discuss in conjunction with other historical-geographical writers.1 Each in his own way expressed one major paradox inherent in the labyrinth image: its status as simultaneously a great and complex work of art and a frightening and confusing place of interminable wandering—the labyrinth as order and as chaos, depending on the observer’s knowledge and perspective. But there is an important distinction among these seminal describers of the labyrinth: Pliny and other historical-geographical writers were interested chiefly in the facts of the ancient labyrinths, their status as buildings, their design and purpose, the skill of their architects; Ovid, ingenious author of entertaining fiction, was concerned chiefly with the myth (and to some extent the morality) of the Cretan maze, with the labyrinth’s story rather than its structure; but Virgil, grand predecessor of both, writing fiction freighted with quasi-historical authority, was fascinated with story and structure, the path through the maze as well as its elaborate pattern. In this chapter we will see some of the literary effects of these various preoccupations.

Later writers, like their classical prototypes, also tend to emphasize either fact or fiction, building or legend, in their variations on the theme of the labyrinth. Writers emphasizing objective fact often follow Pliny by stressing magnificence of design, the maze as artistic building; those more concerned with myth or fiction follow Ovid and typically explore the subjective experience of being within a maze and suffering its intellectual confusions and moral delusions; and some rare authors, such as Dante and Chaucer, share Virgil’s comprehensive vision and arrive at the richest developments of the idea of the labyrinth by blending labyrinthine fact and fiction, structure and story, objective pattern and subjective path. Metaphorical uses of the labyrinth to connote brilliant artistry often depend ultimately on the historical-geographical tradition of the labyrinth as a real building of dazzling complexity, viewed from a privileged perspective or with the sophistication of an architectural connoisseur, whereas metaphors involving confusion, error, and entrapment often rely more on the fictional-mythical tradition and an identification with those trapped in the maze.

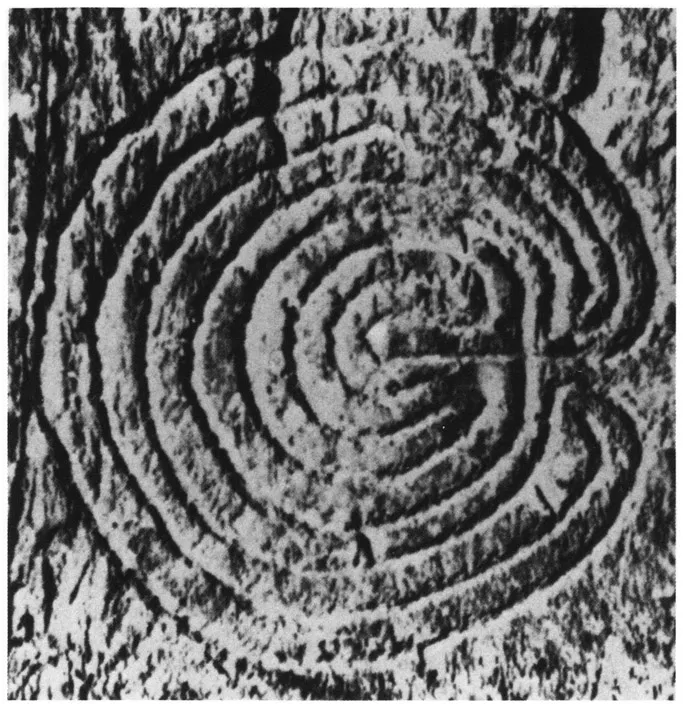

The myth of the many-pathed (“multicursal”) Cretan labyrinth existed in some form as early as Homer, who describes on Achilles’ great shield the dancing-floor that Daedalus made in Crete for Ariadne, a passage often interpreted as alluding to the labyrinth.2 The labyrinth design in the visual arts—a square or circular diagram in which a single unbranched (“unicursal”) circuitous route leads inevitably, if at great length, to the center—is older still, dating back to prehistoric times (see plate 1).3 Since this book must recognize some limits, I focus on the classical works most influential in early Christian and medieval times. Thus the origins and early transmission of myth and visual image alike—subjects of speculation rather than of knowledge—lie beyond my scope, and I regretfully exclude some classical treatments of the story as well.4 The conflict between literary and visual models of the labyrinth, to which I have just alluded, is touched on here and there in this chapter when the subject naturally arises from the texts; it becomes the major theme of Chapter 2.

1. Typical Cretan-style labyrinth design. One of two labyrinths carved in stone at Rocky Valley, near Tintagel, Cornwall (ca. 1800–1400 B.C.). Photograph courtesy of Edwin H. Gardner.

Here I address the most significant classical literary witnesses, and because labyrinthine “facts” in some sense underlie poetic fiction, I begin with the historical-geographical tradition, which describes not only the Cretan maze familiar to modern readers but also other ancient labyrinths, telling us what they looked like, how and why they were built, and what they were used for. This tradition, highlighting labyrinthine artistry, is at least as old as Herodotus (fifth century B.C.) and encompasses a number of authorities. Although Pliny’s description of ancient labyrinths is comparatively late, among historical-geographical accounts it is fullest and best-known in the Middle Ages, and thus it provides a good framework for further discussion.5

Pliny considers the four labyrinths of the ancient world in the context of great architectural achievements, among which the labyrinths (in Egypt, Crete, Lemnos, and Etruria) were the most extraordinary (portentosissimi), incredibly complex in construction and inordinately expensive to build; the Etruscan labyrinth, the tomb of Lars Porsenna, in particular was an “insane folly” that “exhausted ... the resources of a kingdom.” Pliny assures his readers (perhaps those skeptical of the Cretan myth?) that these magnificent creations are “by no means fictitious.” His emphasis on the labyrinths’ architectural splendor is anticipated by Herodotus, who visited the Egyptian maze and found it even more splendid than the pyramids: “If one were to collect together all the buildings of the Greeks and their most striking works of architecture, they would all clearly be shown to have cost less labor and money than this labyrinth.” Diodorus Siculus (fl. 49 B.C.) concurs, stressing the magnificence and magnitude of the Egyptian maze, whose artistic carvings, ceiling paintings, relics, and murals would have made it insurpassable in execution, had it ever been finished.

The artistic preeminence of these labyrinths derives partly from the excellent artwork they contain but chiefly from their immensely complicated structure. Oldest and most illustrious of all was the Egyptian maze, which Pliny describes as still extant. This impressive monument inspired Daedalus, whose Cretan labyrinth, a markedly inferior copy, included only a hundredth of the “passages that wind, advance and retreat in a bewilderingly intricate manner [quae itinerum ambages occursusque ac recursus inexplicabiles]” in the Egyptian exemplar.6 Not surprisingly, Pliny finds it impossible to describe precisely the ground plan of this complex building with its winding passages, vast halls, and temples.7 The “bewildering maze of passages [viarum illum inexplicabilem errorem]” consists of several storeys above and below ground crammed full of columns, galleries, porches, and statues of gods, kings, and monsters. Most of the edifice is dark and noisy, for the passages are vaulted with marble and arranged so that “when the doors open there is a terrifying rumble of thunder within.”

As if the maze were not already hard enough to visualize, Pliny reminds his contemporaries that this labyrinth bears no resemblance to the mazes they know: “It is not just a narrow strip of ground comprising many miles of ‘walks’ or ‘rides,’ such as we see exemplified in our tessellated floors or in the ceremonial game played by our boys in the Campus Martius, but doors are let into the walls at frequent intervals to suggest deceptively the way ahead and to force the visitor to go back upon the very same tracks that he has already followed in his wanderings [sed crebris foribus inditis ad fallendos occursus redeundumque in errores eosdem].” According to Pliny, then, the Egyptian labyrinth is quite unlike the unicursal, two-dimensional mosaic labyrinths surviving in some abundance from the classical period: these have no false turnings and offer no real possibility of getting lost but instead involve repeated turns and twists that infallibly guide the eye, finger, or footstep to the center (see plate 3).8 Nor is it like the lusus Troiae, that horse-ballet/tournament ritual with interlocking paths so popular in imperial Rome, of which more later. Instead, the Egyptian building is a multicursal architectural construction, multistoreyed, full of twisting corridors and doors and halls, whose darkness and myriad passages would make a stranger become irretrievably lost.

As there is unanimity on the magnificence of the ancient labyrinths as works of art, so too there is agreement on the complexity of their floorplans. But some dissension exists concerning the exact nature of that complexity. Pliny explicitly contrasts the more complicated multicursal form of the Egyptian (and, by extension, the Cretan) labyrinth with the unicursal design of mosaic floors, and early authorities agree that one could easily get lost in three-dimensional labyrinths. But an intriguing hint of confusion between unicursal and multicursal designs may be found in Pomponius Mela’s account of the Egyptian building, which has “one descent down to it, but inside has almost countless routes which are doubtful [ancipites] because of the many deviations, which turn this way and that with a continuous curvature, and entrances that are often dead ends [revocatis]. The labyrinth is entangled by these routes, which impose one circle on another; by their bending, which constantly returns as far as it had progressed; and by a wandering which is extensive but which can nevertheless be unraveled.” Mela seems to want it both ways: the building’s many paths, multiple internal entrances, and dead ends are sure signs of an inextricable, multicursal maze, yet at the same time he apparently envisages a single entry to the whole maze and a continuously curving path, winding back and forth, that eventually leads to extrication—a design that would resemble the unicursal pattern. Perhaps Mela simply blurred Pliny’s careful formal distinction in trying to describe the maze’s groundplan in words; but this uncertainty—or is it a tendency to see the maze as both unicursal and multicursal?—is characteristic of much classical and medieval thought and may reflect a reconciliation of the unicursal model familiar in art with the multicursal model of literature. We return to this subject in the next chapter.

If the great labyrinths are structurally so complex that they confuse wanderers and writers alike, why so? What is the reason for such elaborate structure? The historian-geographers do not tell us directly, but they permit informed guesses. One reason may be purely aesthetic. Labyrinths are insurpassable paragons of architectural skill, and many writers make a point of preserving the names of the architects: the maze-maker Daedalus’s fame is widespread, and Pliny mentions the restorer of the Egyptian maze and the Lemnian architects while noting with chagrin that the forgotten designer (artifex) of the Etruscan maze deserved greater praise than its vainglorious sponsor, Lars Porsenna. As the pinnacles of human art, labyrinths might well be intensely complicated and artificial: the more elaborate, the more beautiful. As highly important buildings, too, labyrinths might fitly be intricate. True, the precise functions of ancient mazes were open to debate. According to some sources, the Egyptian and Etruscan labyrinths were monuments to their commissioners, who were either entombed within or simply memorialized. Others suggest that the Egyptian labyrinth was, or included, a great palace.9 As witness to the preeminence of patrons and architects alike, an ornate and intricate structure, “greater than all human works” according to Herodotus, is justifiable on purely artistic grounds. So too if, as Pliny reports, the labyrinth was a temple to the Sun-god and contained precincts for all the Egyptian gods.10 The religious and commemorative functions of ancient labyrinths suggest another reason for complex structure: as protection, to impede access to sacred places or to deny a quick escape to thieves or the sacrilegious. We will see variations on many of these putative functions of the Egyptian labyrinth later: the complex architectural splendor of a labyrinth makes both a compelling propagandistic statement honoring architect or commissioner and an effective defense against intrusion. Form follows function.

Although there may be ample aesthetic and pragmatic justification for the intricacies of the Egyptian, Lemnian, and Etruscan mazes (the Cretan labyrinth presents a different problem, as we shall see), the effect of such buildings is curiously double, enforcing dismay as well as delight. Pliny notes that visitors to the Egyptian labyrinth are “exhausted with walking” even before reaching “the bewildering maze of passages,” and he cites Varro’s description of the pyramid-bedecked “tangled labyrinth [labyrinthum inextricabile]” in Etruria, “which no one must enter without a ball of thread if he is to find his way out.” Even with a guide, Herodotus experienced “countless marvelings” at the Egyptian maze’s “extreme complication,” and he never penetrated the dangerous lower chambers inhabited by dead kings and sacred crocodiles. Strabo comments that “no stranger can find his way either into any court or out...