![]()

PART 1

Restorative Practice

![]()

1

Restorative Practice

The Basics

Restorative practice (RP) is a term we use to describe the practice of the philosophy and processes of restorative justice (RJ), an approach in response to wrongdoing that places the focus of problem- solving on harm done and how that might be repaired. It contrasts with a more traditional, retributive approach that focuses on who was responsible for the wrongdoing and how they should be punished.

Schools, youth detention centres, residential care facilities, government departments and agencies working with youth and children, such as police, have a history that has been influenced by dominant paradigms in the criminal justice system and parenting styles which have been typically authoritarian, although this is slowly changing through the increasingly rapid pace of social evolution (Grille 2005). Over the past two decades, early experiments in restorative justice in policing, youth justice and adult justice (Stephenson 2014) and school disciplinary approaches have seen such positive outcomes in behaviour and culture change (IIRP 2009; McKenzie 1999; Shaw and Wierenga 2002; Thorsborne and Blood 2013) that we are now beginning to see wider adoption of this approach in these sectors.

For readers who are unfamiliar with the differences in the two approaches, Table 1.1 will help in drawing comparisons. It demonstrates two differing views of accountability. On one hand, wrongdoers are held accountable by punishment for rules and laws broken. On the other, wrongdoers are held accountable for the harm they have done and must take responsibility for the impact on others and seek to repair that harm.

| Table 1.1 Two paradigms |

| Crime and wrongdoing are violations against the laws/rules: What laws/rules have been broken? | Crime and wrongdoing is violation of people and relationships: Who has been harmed? In what way? |

| Blame must be apportioned: Who did it? | Obligations must be recognized: Who are these? |

| Punishment must be imposed: What do they deserve? | How can the harm be repaired? |

A disciplinary process in a school or other youth setting, to be regarded as restorative, must have three basic considerations evident (Zehr 2002). These are harm, obligations, and engagement or participation:

• Harm: there is focus on victims and their needs in the wake of an incident. Harm has been done to people and relationships. What is the nature of that harm and how might it be repaired? This view of harm is not, though, limited to victims. We are also concerned about the harm to wrongdoers themselves, supporters of wrongdoers, victims supporters and others who may have been affected by virtue of their roles within the institution (e.g. the deputy principal or head who had to investigate, the teacher on duty, the police officer who made the arrest) and the wider community.

• Obligations: there is focus on responsibility and accountability with those involved. The person responsible must be helped to understand the impact of their behaviour on others, take responsibility for this harm and repair that harm to the extent that it is possible. These obligations are not limited to the wrongdoer. They are shared with the wider community that must take responsibility for what may have contributed to the incident or situation, make changes to minimise the likelihood of further harm, and provide support for those who most need it, whether they are wrongdoers or victims or their families.

• Engagement or participation: the people in the problem are included in the problem-solving. In other words, there is engagement and participation of the key people in telling their stories, exploring the harm done, deciding what to do about repairing the harm and resolving the issues that contributed to the incident. All too frequently, when wrongdoing occurs, some official in the school or organisational hierarchy (the deputy principal or head, or the residential care manager) tells the affected community what will happen to the person responsible. These decisions are often laid out in policy and procedures (Do A and the consequence is B), and the person in authority simply follows policy and ‘dispenses’ justice. There is little opportunity for the people affected by the incident to engage in the problem-solving or to have a voice in the process.

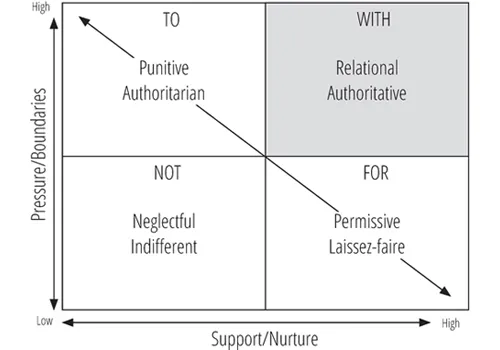

Another useful way to compare discipline styles is to look more broadly at approaches through a framework known variously as the social control window (Glaser 1969; Watchel 1999) or the social capital window (Blood 2004). In Figure 1.1 we have sought to combine a number of ideas around criminal justice, education, parenting and leadership styles that are not limited just to retribution and restoration (Glaser 1969; Watchel 1999).

Figure 1.1 Social capital window

Adapted from Watchel, 1999. Reproduced with permission, Thorsborne and Blood, 2013.

The four quadrants show differences in the levels and styles of pressure or expectations, and support that are applied by an adult when the young person does something wrong. It is fair to say that most of us do not remain completely in one quadrant one hundred per cent of the time when dealing with wrongdoing. Our position will be influenced by how overloaded we are, how well or unwell we might be, how trying the circumstances are with a particular young person with whom all goodwill might have been eroded, or when we are ourselves at a low ebb. Another significant variable that affects our approach is how we believe children ought to be raised, how we should shape behaviour and how they should be treated when they do something wrong. This will be a result of how we were raised ourselves – and whether or not we value or question that approach. It will also be influenced by our race, culture, religion and the country we were raised in.

Restorative institutions have managed over time to create a culture of problem-solving based in the authoritative/restorative quadrant. What follows is a description of the mindset or paradigm in each of the quadrants. While you read on, we hope you can begin to think about where your own practice might lie (on a good day or a bad day) and what is the mindset/culture of the institution where you are working.

Authoritarian:

•high demand/pressure, low support

•achievement of compliance/obedience as a priority

•serves the need for order, discipline, predictability

•accountability through punishment (making the person pay)

•coercive (‘do it or else’; rewarding obedience)

•deterrence (message to wrongdoer and others)

•inflexible, rigid about the rules

•context of rule-breaking not considered

•no need to explain decisions

•distance/coolness in the relationship

•respect for authority is one way (bottom up)

•decisions are top down

•wrongdoers and victims have no voice in the process of decision-making.

Laissez-faire/permissive:

•high support, low pressure/demand

•wrongdoer’s needs are placed at the centre of the problem-solving with little consideration for the needs of the person harmed

•excusing the behaviour (‘they can’t help themselves’)

•rescuing the person responsible from the consequences of the wrongdoing (adult being the voice for the child, with no engagement from the child who is disengaged while the adult problem-solves)

•overprotective

•few boundaries and limits

•support at the expense of accountability, with welfare of wrongdoer overriding breaches of standards and welfare of affected others

•eventually, little respect for authority

•when issues/chaos become too much...