eBook - ePub

Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience

An Introduction

Mark H. Johnson, Michelle D. H. de Haan

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience

An Introduction

Mark H. Johnson, Michelle D. H. de Haan

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 4th Edition, is a revised and updated edition of the landmark text focusing on the development of brain and behaviour during infancy, childhood, and adolescence.

- Offers a comprehensive introduction to all issues relating to the nature of brain-behaviour relationships and development

- New or greatly expanded coverage of topics such as epigenetics and gene expression, cell migration and stem cells, sleep and learning/memory, socioeconomic status and development of prefrontal cortex function

- Includes a new chapter on educational neuroscience, featuring the latest findings on the application of cognitive neuroscience methods in school-age educational contexts

- Includes a variety of student-friendly features such as chapter-end discussion, practical applications of basic research, and material on recent technological breakthroughs

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience von Mark H. Johnson, Michelle D. H. de Haan im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Psicologia & Neuroscienza e neuropsicologia cognitiva. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1

The Biology of Change

In this introductory chapter we discuss a number of background issues for developmental cognitive neuroscience, beginning with historical approaches to the nature–nurture debate. Constructivism, in which biological forms are an emergent produc3t of complex dynamic interactions between genes and environment, is presented as an approach to development that is superior to accounts that seek to identify preexisting information in genes or the external environment. However, if we are to abandon existing ways of analyzing development into “innate” and “acquired” components, this raises the question of how we should best understand developmental processes. One scheme is proposed for taking account of the various levels of interaction between genes and environment. In addition, we introduce the difference between innate representations and architectural constraints on the emergence of representations within neural networks. Following this, a number of factors are discussed that demonstrate the importance of the cognitive neuroscience approach to development, including the increasing availability of brain imaging and molecular approaches. Conversely, the importance of taking a developmental approach to analyzing the relation between brain structure and cognition is reviewed. In examining the ways in which development and cognitive neuroscience can be combined, three different perspectives on human functional brain development are discussed: a maturational view, a skill learning view, and an “interactive specialization” framework. Finally, the contents of the rest of the book are outlined.

1.1 Viewpoints on Development

As every parent knows, the changes we can observe during the growth of children from birth to adolescence are truly amazing. Perhaps the most remarkable aspects of this growth involve the brain and mind. Accompanying the fourfold increase in the volume of the brain during this time are numerous, and sometimes surprising, changes in behavior, thought, and emotion. An understanding of how the developments in brain and mind relate to each other could potentially revolutionize our thinking about education, social policy, and disorders of mental development. It is no surprise, therefore, that there has been increasing interest in this new branch of science from grant-funding agencies, medical charities, and even presidential summits. Since the publication of the first edition of this book in 1997, this field has become known as developmental cognitive neuroscience.

Developmental cognitive neuroscience has emerged at the interface between two of the most fundamental questions that challenge humankind. The first of these questions concerns the relation between mind and body, and specifically between the physical substance of the brain and the mental processes it supports. This issue is fundamental to the scientific discipline of cognitive neuroscience. The second question concerns the origin of organized biological structures, such as the highly complex structure of the adult human brain. This issue is fundamental to the study of development. In this book we will show that light can be shed on these two fundamental questions by tackling them both simultaneously, specifically by focusing on the relation between the postnatal development of the human brain and the emerging cognitive processes it supports.

The second of the two questions above, that of the origins of organized biological structure, can be posed in terms of phylogeny or ontogeny. The phylogenetic (evolutionary) version of this question concerns the origin of species and has been addressed by Charles Darwin and many others since. The ontogenetic version of this question concerns individual development within a life span. The ontogenetic question has been somewhat neglected relative to phylogeny, since some influential scientists have held the view that once a particular set of genes has been selected by evolution, ontogeny is simply a process of executing the “instructions” coded for by those genes. By this view, the ontogenetic question essentially reduces to phylogeny (e.g., so-called evolutionary psychology). In contrast to this view, in this book we argue that ontogenetic development is an active process through which biological structure is constructed afresh in each individual by means of complex and variable interactions between genes and their respective environments. The information is not in the genes, but emerges from the constructive interaction between genes and their environment (see also Oyama, 2000). However, since both ontogeny and phylogeny concern the emergence of biological structure, some of the same mechanisms of change have been invoked in the two cases.

Further Reading

Oyama (2000).

The debate about the extent to which the ontogenetic question (individual development) is subsidiary to the phylogenetic question (evolution) is otherwise known as the nature–nurture issue, and it has been central in developmental psychology, philosophy, and neuroscience. Broadly speaking, at one extreme the belief is that most of the information necessary to build a human brain, and the mind it supports, is latent within the genes of the individual. While most of this information is common to the species, each individual has some specific information that will make them differ from others. By this view, development is a process of unfolding or triggering the expression of information already contained within the genes.

At the opposing extreme, others believe that most of the information that shapes the human mind comes from the structure of the external world. Some facets of the environment, such as gravity, patterned light, and so on, will be common throughout the species, while other aspects of the environment will be specific to that individual. It will become clear in this book that both of these extreme views are ill conceived, since they assume that the information for the structure of an organism exists (either in the genes or in the external world) prior to its construction. In contrast to this, it appears that biological structure emerges anew within each individual’s development from constrained dynamic interactions between genes and various levels of environment, and it is not easily reducible to simple genetic and experiential components (Scarr, 1992).

It is more commonly accepted these days that the mental abilities of adults are the result of complex interactions between genes and environment. However, the nature of this interaction remains controversial and poorly understood, although, as we shall see, light may be shed on it by simultaneously considering brain and psychological development. Before going further, however, it is useful to review briefly some historical perspectives on the nature–nurture debate. This journey into history may help us avoid slipping back into ways of thinking that are deeply embedded in the Western intellectual tradition.

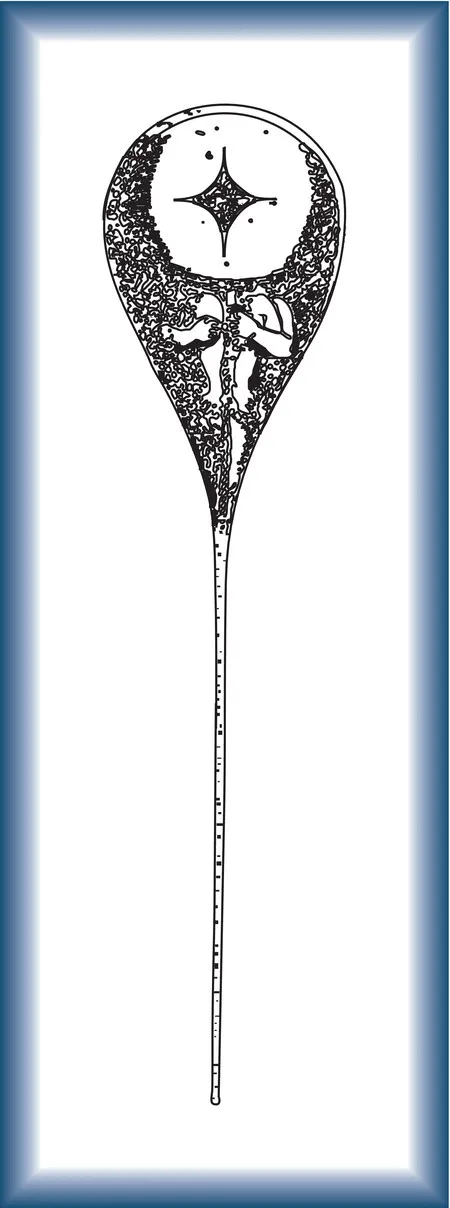

Throughout the 17th century there was an ongoing debate in biology between the “vitalists” on the one hand and the “preformationists” on the other. The vitalists believed that ontogenetic change was driven by “vital” life forces. Belief in this somewhat mystical and ill-defined force was widespread and actively encouraged by some members of the clergy. Following the invention of the microscope, however, some of those who viewed themselves as being of a more rigorous scientific mind championed the preformationist viewpoint. This view argued that a complete human being was contained in either the male sperm (“spermists”) or the female egg (“ovists”). In order to support their claim, spermists produced drawings of a tiny, but perfect, human form enclosed within the head of sperm (see Figure 1.1). They argued that there was a simple and direct mapping between the seed of the organism and its end state: simultaneous growth of all the body parts. Indeed, preformationists of a religious conviction argued that God, on the sixth day of His work, placed about 200,000 million fully formed human miniatures into the ovaries of Eve or sperm of Adam (Gottlieb, 1992)!

Figure 1.1 Drawings such as this influenced a seventeenth-century school of thought, the “spermists,” who believed that there was a complete preformed person in each male sperm and that development merely consisted of increasing size.

Of course, we now know that such drawings were the result of overactive imagination and that no such perfectly formed miniature human forms exist in the sperm or ovaries. However, as we shall see, the general idea behind preformationism, that there is a preexisting blueprint or plan of the final state, has remained a pervasive one for many decades in biological and psychological development. In fact, Oyama (2000) suggests that the same notion of a “plan” or “blueprint” that exists prior to the development process has persisted to the present day, with genes replacing the little man inside the sperm. As it became clear that genes do not contain a simple “code” for body parts, in more recent years, “regulator” and “switching” genes have been invoked to orchestrate the expression of the other genes. Common to all of these versions of the nativist viewpoint is the belief that there is a fixed mapping between a preexisting set of coded instructions and the final form. We will see in Chapter 3 that we are discovering that the relationship between the genotype and its resulting phenotype is much more dynamic and flexible than traditionally supposed.

On the other side of the nature–nurture dichotomy, those who believe in the structuring role of experience also view the information as existing prior to the end state, only the source of that information is different. This argument has been applied to psychological development, since it is obviously less plausible for physical growth. An example of this approach came from some of the more extreme members of the behaviorist school of psychology who believed that a child’s psychological abilities could be entirely shaped by its early environment. More recently, some developmental psychologists who work with computer models of the brain have suggested that the infant’s mind is shaped largely by the statistical regularities latent in the external environment. While such efforts can reveal hitherto unrecognized contributions from the environment, it will become evident in this book that these ...