![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: Dimensions of Treatment for Traumatized Children

“It hurts inside,

it hurts inside,

it hurts inside so baaaad”

This was the sing-song refrain of Racquel, a seven-year-old little girl who had just survived a night sleeping on her front porch. She arrived at school that morning dressed in the same clothes she had worn the day before and complaining of being hungry. Her teacher reported that she was uncontrollable in the classroom, aggressively engaging her peers and disrupting the other students. She was sent to my office, where she sat down on the couch with her arms crossed over her chest and glared at me defiantly. She looked at me with hot tears held back by sheer willpower and said, “I don’t want to talk about it.” I explained that sometimes it was difficult to talk about feelings, but that they could get out through music or drawing. Racquel looked at me thoughtfully and then reached for the toy guitar and began to strum these words in a frenzied rhythm, repeating them over and over again until she reached a fever pitch. Then she sighed, put the guitar aside, and sat back down. The tears began to flow, and so did her tale. Mom had gone out prostituting herself in an attempt to keep the family afloat financially but had forgotten to leave a key under the mat.

The fact is that our traumatized children do hurt inside. Sometimes the hurt comes out in externalizing behavior problems. Sometimes the hurt is held close and causes a host of internalizing symptoms. Either way, child therapists become, in our use of self and the space, the strong containers who help to hold the hurt for the children we serve. This book highlights the many ways a therapist holds trauma content for a child, while navigating a developmentally sensitive, individualized course of treatment.

The Goals of This Text

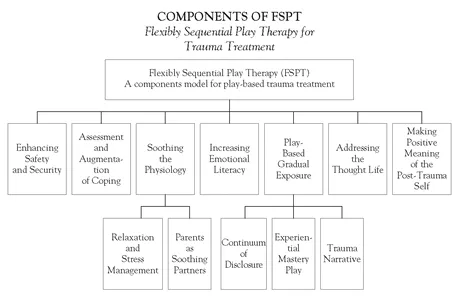

The aim of this book is threefold. The first objective is to outline my approach to trauma treatment, what I have termed the flexibly sequential play therapy (FSPT) model of treatment for traumatized children. Although each child is unique, each case is different, and all require the finesse of a skilled clinician, a series of foundational treatment goals come up over and over again during a course of therapy for a traumatized child. They are:

1. Building a child’s sense of safety and security within the playroom and in relation to the person of the therapist

2. Assessing and augmenting coping skills

3. Soothing the physiology

4. Using parents as partners: Ensuring that caregivers are facilitative partners in the therapy process and effective co-regulators of the child’s affect

5. Increasing emotional literacy

6. Creating a coherent narrative of the trauma that integrates the linguistic narrative with somatosensory content

7. Addressing the thought life, including challenging faulty attributions and cognitive distortions while restructuring maladaptive cognitions and installing and practicing adaptive thoughts

8. Making positive meaning of the post-trauma self

In addition to these treatment goals, the rich environment of the playroom encourages two other processes that I have seen play out over and over again as children work through trauma. I have labeled the first of these the continuum of disclosure, which refers to the ways in which children self-titrate their exposure to trauma content. The second phenomenon is called experiential mastery play (EMP) and refers to the myriad ways in which children use the play space and the tools of childhood to restore the sense of empowerment that posttraumatic children have often lost. These twin processes, grounded in play and expressive mediums and woven throughout the other skill-based work, are so pervasive with traumatized children that each is given its own chapter.

Figure 1.1 Components of FSPT

The FSPT model delineates specific treatment goals, delivered through a variety of specific play-based technologies and supported by an understanding of the facilitative powers of play and the therapist’s use of self in the play space. The specific needs and symptom constellations of each child require a flexible, nuanced application of the model and also leave room for the integration of nondirective and directive approaches. The sequence is also flexible with respect to both chronological order and the length of time that is spent in the pursuit of each goal. The goals are laid down sequentially. This delineation may give the faulty impression that each goal can be fit neatly into a box and done in an ordered fashion with every client. The opposite is more likely to be true.

Although the skill sets may be introduced in a certain order, it is often the case that several goals are being pursued simultaneously. For example, although trauma narrative work is generally saved until the child has established a strong foundation of positive coping, relaxation strategies have been rehearsed, and parent support has been increased, children may begin to share trauma content spontaneously. It is the therapist’s job to become a container for this content, record it in some fashion as part of the narrative, and, if necessary, invite the child back into safer territory.

The flexible nature of FSPT also allows for steps in the sequence to be skipped if the child or family already seems to have a healthy grasp of the therapeutic content that would otherwise be covered. For example, a child who enters treatment after being involved in a serious car accident may not need to progress through every step of the therapy. He may already have some of the internalized abilities that would be provided through treatment. If he has a strong, contingently responsive caregiver, he is likely to already have internal capacities for self-soothing based on a history of being soothed by the parent. Additionally, if the parent is not mired in her own trauma reaction and is functioning as a healthy support to the child, the components of treatment related to soothing the physiology and maximizing the role of the caregiver may be minimal. Through careful assessment and clinical judgment, the most salient treatment goals from the model can be mapped out on a case-by-case basis.

The application of FSPT requires breadth of knowledge and finesse with a variety of treatment technologies. Goals such as coping, emotional literacy, and cognitive restructuring require an understanding of cognitive-behavior theory (Beck, 1975, 1979, 2005) and its derivative methodologies for children and adolescents (Asarnow, Tompson, & Berk, 2005; Cohen, Deblinger, Mannarino, & Steer, 2004; Cohen, Mannarino, & Deblinger, 2006), as well as cognitive-behavioral play therapy (Knell, 1993, 1998). Soothing the physiology requires an understanding of trauma theory and developmental traumatology (Briere & Scott, 2006; Cicchetti & Tucker, 1994; DeBellis et al., 1999; DeBellis & Putnam, 1994; Perry & Azad, 1999; Solomon & Siegel, 2003), physiological stress responses (Bremner et al., 2003; DeBellis & Thomas, 2003; Van der Kolk, 1994), and the theoretical underpinnings of somatic therapies (Rothschild, 2000) and mindfulness practices (Kabat-Zinn, 1990, 2005; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002).

Maximizing the role of parents as partners in a child’s trauma treatment requires an understanding of family systems theory and attachment theory and familiarization with the latest dyadic interventions, including parent-child interaction therapy (Herschell & McNeil, 2007; Urquiza & McNeil, 1996), Theraplay (Jernberg & Booth, 2001; Martin, Snow, & Sullivan, 2008; Munns, 2009), filial therapy (Guerney, 1964; Guerney, Guerney, & Andronico, 1999; VanFleet, Ryan, & Smith, 2005), child-parent psychotherapy (Lieberman, Van Horn, & Ippen, 2005, 2006), child-parent relationship therapy (Bratton, Landreth, Kellam, & Blackard, 2006; Landreth & Bratton, 2006), and the Circle of Security Project (Cooper, Hoffman, Powell, & Marvin, 2005; Hoffman, Marvin, Cooper, & Powell, 2006; Marvin, Cooper, Hoffman, & Powell, 2002; Powell, Cooper, Hoffman, & Marvin, 2007). Although it is not necessary to be proficient in every one of the models listed here, it is essential that the modern clinician’s tool kit include sound dyadic interventions and psychoeducation components for the parent.

The developmental needs of children also require that clinicians have a healthy respect for the therapeutic uses of play (Landreth, 1991; Schaefer, 1993; Schaefer & Drewes, 2009) and the effectiveness of play therapy as a treatment modality (Bratton, Ray, Rhine, & Jones, 2005; Ray, Bratton, Rhine, & Jones, 2001). Overlaying all these areas of knowledge should be a great respect for a child’s individuality and a deep belief in a child’s ability to heal from trauma.

The second intention behind this book is to equip clinicians with creative, practical, easily replicable interventions that can be employed to accomplish each of the goals of the FSPT model. The most common concern I hear from practitioners is that techniques and theoretical information about trauma are easy to find, but the blending of solid theoretical groundwork with techniques is more difficult. The application of specific techniques or interventions, without the proper scaffolding of a comprehensive model of treatment in which to place them, may end up producing iatrogenic effects. To this end, an explication of prop-based intervention (PBI) is made. Additionally, all the goal-directed chapters include examples of specific, prop-based play interventions that can be employed in the pursuit of that goal.

The third aim of this book is to accurately convey the myriad ways in which children eloquently articulate and begin to resolve their experiences of traumatic events through play, art, and story. This book is not limited by the form that a particular trauma might take. Case examples include clients who have experienced physical abuse, sexual abuse, domestic violence, divorce, the death of a loved one, tragic accidents, chronic illnesses, and natural disasters.

The Need for Integration

In conference settings, I am often asked, “How should we conceptualize the underlying anxiety problem in posttraumatic children? From a neurophysiological perspective? From a psychodynamic perspective? From a behavioral perspective? From a family systems perspective? From a cognitive perspective?” My answer is unabashedly, “Yes, yes, yes, yes, and yes.” FSPT is both inclusive, in that it recognizes the valuable contributions of widely diverse paradigms to functional trauma treatment, and holistic, in the sense that all aspects of the child’s life (developmental, social, cognitive, filial, neurobiological, etc.) must be considered when planning treatment.

An example may help to flesh out the complexities of treatment. Julie, a ten-year-old girl referred to treatment after witnessing her father violently attack her mother, is suffering from intense separation anxiety. In this case, it can be hypothesized that the avoidance of separation from mom is directly related to the trauma, because Julie had no difficulty separating from mom before the attack. Julie insists on staying in the same room with her mother, even when they are at home during the daytime. Mom is exhausted and bewildered by her daughter’s behavior and vacillates between yelling at her daughter and accusing her of manipulating the situation and feeling guilty about the child’s pain and enabling Julie’s dependence on her. In this case, the child and parent need psychoeducation about the effects of trauma and anxiety and the best mechanisms through which to fight them. The mom needs specific training in strategies that will soothe her daughter while challenging her to push through the anxiety. The parent and child need to create a coherent narrative of the attack together and discharge the toxicity associated with that event. The child needs individualized play-based interventions that will augment her coping, equip her with relaxation strategies, and train her to “boss back” the anxiety and make strides in identifying and restructuring faulty cognitions. A process of graduated exposures will most likely have the greatest success if it is reinforced through behavioral rewards for the child. In addition to these pieces, the child may benefit from spontaneous reenactment of the trauma through the play materials in the room. Yes, yes, yes, yes, and yes.

The trend toward integration promoted by child clinicians from other professional fields is being trumpeted by play therapists as well (Gil, 2006; Kaduson, Cangelosi, & Schaefer, 1997; Shelby & Felix, 2005). Currently many theoretical orientations and working models fall within the scope of play therapy. Although each orientation has a valuable contribution to make, it is critical that clinicians select and tailor intervention models to the unique needs of each client, as opposed to championing one theoretical approach to the exclusion of others.

Clinicians have historically defined themselves in relation to their theoretical orientation. “I am a psychoanalytic therapist.” “I am a cognitive-behavioral therapist.” “I am a child-centered play therapist.” “I am an attachment therapist.” Each of these theoretical orientations birthed a host of technologies that allow for the practical application of each theory. These technologies may include a premeditated way of responding to clients, a series of intentionally designed questions aimed at exploring a particular area of a person’s experience, a set of psychoeducational activities, or a succession of experiential exercises that support the model. Although all of these models have valuable contributions to make to the field of child therapy, no single therapy can claim to be the fix or the cure for every child who comes through our doors. In fact, when we as clinicians have too closely aligned ourselves with one particular mode of practice, we increase the likelihood that we will have clients whom we are unable to help. In these cases, we run the risk of eventually characterizing a clinical failure as one in which the child cannot be helped when what may be more accurate is that we have not yet found the most effective way of helping. With these dangers in mind, it is incumbent upon contemporary child therapists to be well versed in a variety of intervention models.

My own evolution as a trauma therapist may mirror the journey of many readers. I was originally trained in child-centered play therapy (CCPT) and its offshoot, filial therapy, both of which gave me a healthy respect for a nondirective approach and a child’s ability to lead. There will be many examples throughout this text of the magic that can occur when a child is allowed to use play, the language of childhood, to work through her trauma experiences. I am constantly amazed at a child’s ability to spontaneously go where she needs to go, eloquently describing her experiences through the play, art, and sand. I am, however, equally amazed at how a traumatic experience or maltreatment history can rob a child of this same spontaneity. Recognizing the limitations that an exclusively nondirective approach placed on my own practice, I went in search of additional tools.

Racquel, the seven-year-old girl who spent the night on the porch at the start of this chapter, moved from dysregulation to immobilization in the course of the morning. Her tightly crossed arms mirrored her tightly held control. She needed an invitation toward movement, and my offers of music, drawing, or sand play gave her options among which she could choose. The facilitative invitation, while directive in nature, opened the door for her self-directed creation of the “It hurts inside” mantra. In this case, Racquel needed help getting started.

Other aspects of trauma treatment may also require more directive intervention from the therapist. Psychoeducation related to a child’s specific traumatic events and skill building in target areas can both be accomplished through the medium of play but must be intentionally pursued. In addition, some children engage in trauma reenactment play that is repetitive and aimless, often separated from any meaningful thoughts, emotions, or energized movement. Gil (2006) terms this mired play pattern stagnant posttraumatic play. The therapist’s response in these situations requires a range of purposeful invitations to help the child become unstuck.

Another aspect of trauma recovery relates to the restoration of disrupted attachment relationships with caregivers. In some cases a traumatic event has compromised the parent, the child, or both parties to such an extent that they need directive help in reestablishing a relationship of coregulation. In other cases, the depth of maltreatment requires a child to develop a relationship with an entirely new caregiver. In either case, a host of directive interventions exist that purposefully facilitate these connections. Keeping in mind the variety of these needs, the FSPT model embraces both nondirective and directive approaches to treatment, promoting the flexible application of each.

In sum, the FSPT model represents a systematic integration of theoretical constructs and tools drawn from these diverse schools of thought. Nondirective approaches are used in relation to specific goals. Building safety and security in the playroom is often a child-led process that is simply reinforced by the therapist. The broad processes that I term the continuum of disclosure and experiential mastery play and certain aspects of trauma narrative work tend to be child-directed. Directive approaches are implemented to concretize or augment the work done in these categories and are the primary portals through which skill building and psychoeducation occur, both for the children and their caregivers.

The Facilitative Power of Play in FSPT

FSPT relies heavily on the therapeutic and facilitative powers of play to deliver developmentally sensitive treatment. The facilitative power of play forms the foundation for the application of all evidence-based methods delineated in the FSPT model. The integration of play into the delivery of other intervention models can maximize the developmental sensitivity of the model. For example, recent literature highlights challenges in the nuanced application of CBT for children and adolescents (Gravea & Blisset, 2004; Weisz, Southam-Gerow, & McCarty, 2001). Although CBT is the gold standard of evidence-based practice for the treatment of PTSD and depression in children and adolescents, recent concerns have been articulated related to the cognitive limitations of younger children. Children younger than eight may lack the sophisticated cognitive capabilities (processes such as metacognition) that impact the effectiveness of CBT (Holmbeck et al., 2003). According to two separate meta-analyses of CBT treatment with children and adolescents, older children benefited significantly more from treatment than younger children (Weisz, Weiss, Han, Granger, & Morton, 1995; Durlak, Fuhrman, & Lampman, 1991). The integration of play with the cognitive and behavioral information being conveyed may enhance the treatment’s effectiveness....