eBook - ePub

The Hollywood Romantic Comedy

Conventions, History, Controversies

Leger Grindon

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Hollywood Romantic Comedy

Conventions, History, Controversies

Leger Grindon

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

The most up-to-date study of the Hollywood romantic comedy film, from the development of sound to the twenty-first century, this book examines the history and conventions of the genre and surveys the controversies arising from the critical responses to these films.

- Provides a detailed interpretation of important romantic comedy films from as early as 1932 to movies made in the twenty-first century

- Presents a full analysis of the range of romantic comedy conventions, including dramatic conflicts, characters, plots, settings, and the function of humor

- Develops a survey of romantic comedy movies and builds a canon of key films from Hollywood's classical era right up to the present day

- Chapters work as discrete studies as well as within the larger context of the book

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Hollywood Romantic Comedy un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Hollywood Romantic Comedy de Leger Grindon en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas y Historia y crítica cinematográficas. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Edición

1Categoría

Historia y crítica cinematográficasChapter 1

Introduction

Romantic comedies, from classics such as Trouble in Paradise (1932) to recent hits like Knocked Up (2007), have been a cornerstone of Hollywood entertainment since the coming of sound. Success in romantic comedy has created stars from Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant to Julia Roberts and Ben Stiller. In spite of being popular movies with a long and continuous history of production, romantic comedies have won only a few Oscars for Best Picture: It Happened One Night (1934), You Can't Take It With You (1938), The Apartment (1960), Annie Hall (1977), and Shakespeare in Love (1998). Romantic comedies are often dismissed as formulaic stories promoting fantasies about love. But these comedies have a pedigree that includes William Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and Oscar Wilde. Moreover, these films reward study because they deal with dramatic conflicts central to human experience. From those conflicts arise the familiar conventions that form the foundation for the romantic comedy and portray our social manners surrounding courtship, sexuality, and gender relations.

An American Film Institute 2008 poll defined romantic comedy as “a genre in which the development of romance leads to comic situations.” Billy Mernit in his guide Writing the Romantic Comedy claims that the central question is “will these two individuals become a couple?” (2000: 13). He argues that the romance must be the primary story element. Film scholars explain that romantic comedy is a process of orientation, conventions, and expectations (Neale and Krutnik 1990: 136–49). The film industry orients audiences through titles like Lover Come Back (1961), by casting stars identified with the genre like Meg Ryan, and with advertising and publicity. Filmmakers adapt conventions from successful films in the genre, while adding new elements to keep the movie fresh. Fans select their entertainment by drawing upon their viewing experience to anticipate familiar story turns, such as flirtatious quarreling, and a particular emotional tone shaped by humor.

Gerald Mast explains that the films in the genre create a comic climate through a series of cues to the audience: subject matter is treated as trivial, jokes and physical humor make fun of events, and characters are protected from harm. Even though the drama poses serious problems, such as choosing a life partner, the process appears lighthearted, anticipating a positive resolution (1979: 9–13). The plot of most romantic comedies could be presented with the earnestness of melodrama, but the humorous tone transforms the experience. The movie assumes a self-deprecating stance which signals the audience to relax and have fun, for nothing serious will disturb their pleasure. However, this sly pose allows comic artists to influence their audience while the viewers take little notice of the work's persuasive power.

If humor establishes the tone, courtship provides the plot. In a broad sense the subject of romantic comedy is the values, attitudes, and practices that shape the play of human desire. Mernit claims that the transforming power of love is the overarching theme (2000: 95). More than sexuality, these films portray a drive toward marriage or long-term partnership. Indeed, romantic comedy portrays the developments which allow men and women to reflect upon romance as a personal experience and a social phenomenon. As a result, scholars, such as Celestino Deleyto speak of romantic comedy engaging in the discourse of love, representing the shifting practice of, and the evolving ideas about, romance in our culture.

In cinema, contemporary genre analysis has focused on evolving narrative conventions as a dramatization of pervasive social conflicts. As Thomas Schatz explains, genre criticism treats familiar stories that “involve dramatic conflicts, which are themselves based upon ongoing cultural conflicts” (1981: viii). Guided by the practice of Schatz among others, this study will explore the patterns of meaning in the romantic comedy genre by surveying its animating conflicts, the model plot, the major characters, the function of masquerade, the use of setting, and the viewer's emotional response. With this in mind, let us follow Rick Altman's principle that “The first step in understanding the functional role of Hollywood genre is to isolate the problems for which the genre provides a symbolic solution,” and turn to the conflicts that set the Hollywood romantic comedy film in motion (1987: 334).

Conflicts

These conflicts are as old as courtship, yet each film fashions them to contemporary circumstances. The three major fields of conflict are those between parents and children, those between courting men and women, and those internal to each of the lovers.

First, consider the conflicts between generations, that is, the parents or other authority figures versus their children as lovers and prospective mates. Parents, particularly fathers, represent the established order, reasoned judgment as opposed to the passion of the lovers. The older generation calls on social tradition, the power of the law, and the bonds of family to guide impetuous youth toward a proper and stable union. Lovers counter with the attractions of instinct, the force of their feelings, and the need for a fresh partnership which explores the unknown. In an implicit sense the confrontation between the old society and the new represents the struggle against incest: that is, the need to move outside the family toward a synthesis that will yield the unexpected and the original.

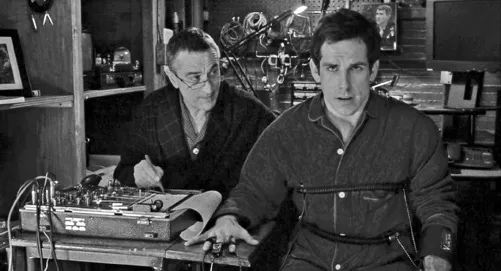

Romantic comedy has portrayed this ancient struggle since the birth of Western theater, as the works of Menander and Terence show us. Shakespeare follows this pattern in A Midsummer Night's Dream, which opens with Egeus petitioning the Duke of Athens to command his daughter Hermia to marry Demetrius, the man of his choice, instead of Lysander, who has bewitched her with verses, love tokens, and moonlight. Instead, Lysander and Hermia flee the law into the enchanted forest to realize their destiny. Rather than displaying the respect due to elders, romantic comedy is more likely to mock fathers as rigid tyrants who stand in the way of change. The contemporary cinema still finds this conflict compelling. In Meet the Parents (2000) Greg Focker (Ben Stiller) must endure the torments of his girlfriend's family before he can realize his engagement. The father, Jack Byrnes (Robert De Niro), former CIA interrogator, turns his professional skills on the innocent young man and almost sabotages the romance. In My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002) Toula Portokalos (Nia Vardalos) must cope with her father's ethnic pride in their Greek heritage when she introduces her Anglo-Saxon fiancé. Romantic comedy expresses its subversive social implications in that the conflict between generations results in the overthrow of the old by the young, but its counter-tendency toward stability results in the eventual reconciliation of the feuding parties in the creation of a new family.

Plate 1 Meet the Parents (2000) poses the conflict between children and parents. Greg Focker (Ben Stiller) is interrogated by his prospective father-in-law Jack Byrnes (Robert De Niro).

Second, the battle between the sexes establishes the central field of conflict animating romantic comedy. This contest evokes the distinct gender cultures within which men and women have been raised. Courting couples must struggle to find common ground upon which to build their union while also establishing sufficient knowledge of, and sympathy for, the opposite sex. In this sense lovers must struggle against the threat of narcissism and seek an identity in difference, an attraction to their opposite that complements and completes the self. As Brian Henderson explains, “Romantic comedy posited men and women willing to meet on a common ground and to engage all their faculties in sexual dialectic” (1986: 320). In darker terms, men and women need to overcome a fear of the opposite sex and embrace heterosexuality as a commanding force driving them toward union.

The genre testifies to the evolving qualities characterizing opposing gender cultures, whether it is the opposition between the rational man versus the intuitive woman in Bringing Up Baby (1938), the masculine sports world versus a feminine arts community in Designing Woman (1957), or competition versus cooperation in Jerry Maguire (1996). Romantic comedies portray the changing status of women in modern times. As a result, the negotiation within the couple over the woman's social role has become a prime feature of the genre (Neale and Krutnik 1990: 133). Kate's submission to Petruchio at the conclusion of The Taming of the Shrew offends many in the contemporary audience, which may be more comfortable with the legal victory of Amanda (Katharine Hepburn) over Adam (Spencer Tracy) in Adam's Rib (1949), but the contest, resistance, and compromise between men and women remain central to the romantic comedy.

The opposition between the gender cultures is frequently amplified by other inherited social distinctions which become a source of tension. For example, the difference in class between the unemployed journalist Peter Warne (Clark Gable) and the wealthy socialite Ellie Andrews (Claudette Colbert) in It Happened One Night is a conflict widespread in the screwball comedies of the 1930s. Woody Allen's romantic comedies, such as Annie Hall, present the conflict between Jew and Gentile. Regional distinctions and their attendant mores can serve as the basis for conflict, as in The Quiet Man (1952). In most cases these inherited social differences embellish the opposing gender traits that serve as an obstacle for the couple.

Another widespread conflict is personal development versus self-sacrifice. Both men and women need to establish an independent and mature character in preparation for a healthy marriage. In many cases, such personal growth involves achieving career goals, such as when Lily Garland (Carole Lombard) develops into an actress in Twentieth Century (1934), C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) becomes a corporate executive in The Apartment, or Will (Joseph Fiennes) overcomes writer's block in Shakespeare in Love. On the other hand, putting aside one's personal interests for the benefit of the beloved is the crucial sign that the new partner can undertake the sacrifices necessary to form a long-term union. As Lord Arthur Goring (Rupert Everett) tells Mrs. Laura Cheveley (Julianne Moore) in An Ideal Husband (1999): “Love cannot be bought, it can only be given…. To give and not expect return, that is what lies at the heart of love.” Kristine Brunovska Karnick explains, “Both partners must make some sacrifice to reach the correct balance between professional and personal concerns” (1995: 132–3). However, in some comedies, particularly the “nervous romances” following Annie Hall in the 1970s and 1980s, the conflict between professional and personal concerns thwarts the couple. For example, in Broadcast News (1987) the romantic triangle between co-workers Tom (William Hurt), Jane (Holly Hunter), and Aaron (Albert Brooks) ends without generating a couple. Each of the characters departs in pursuit of professional goals, and in the epilogue years later, Jane still has been unable to find a partner because her professional ambitions hamper her personal life. This tension between personal development and self-sacrifice serves as a conflict pervasive in romantic comedies.

The challenge of monogamy poses the conflict between a long-term commitment versus a short-term liaison. The teen Tracy (Mariel Hemingway) tells her middle-aged lover Isaac (Woody Allen) in Manhattan (1979), “Maybe people weren't meant to have one chief relationship. People were meant to have a series of relationships of different lengths.” As will be discussed below, an important variation within the genre is the infidelity plot, in which one member of the couple strays and the film plays out whether the initial union will be reestablished. The sociologist Anthony Giddens writes of “confluent love” as a “pure” but contingent relationship presenting an important alternative to marriage in the late twentieth century (1992: 61–4), and this trend toward the temporary relationship rather than “living happily ever after” is evident in romantic comedies such as Semi-Tough (1977), She's Gotta Have It (1986), and Singles (1992).

Along with the changing nature of heterosexual partnership comes a shift from the family to the growing influence of friends. David Shumway notes that in the contemporary romantic comedies he calls “relationship stories friends replace relatives as the chief social grouping” (2003: 164). Friendship also offers an alternative to the couple that can develop into a conflict between sexual love and platonic fellowship. Chasing Amy (1997) clearly poses the conflict between loyalty to one's friend as opposed to pursuing romance. On the other hand, My Best Friend's Wedding (1997) finds Jules (Julia Roberts) jealous when her best friend Michael (Dermot Mulroney) decides to marry Kimberly (Cameron Diaz). Eventually Jules ends the film dancing with her gay confidant George (Rupert Everett) rather than in love. Deleyto has argued that in romantic comedy of the past two decades “heterosexual love appears to be challenged and occasionally replaced by friendship” (2003: 168). The increasing presence of homosexuality presents a related challenge. At least as early as Manhattan, the gay relationship has emerged on film as a threat to partnering between men and women. Other films, such as Chasing Amy or Kissing Jessica Stein (2001), develop homosexuality as a viable option.

The third field for dramatic conflicts within romantic comedy arises within the psyche of the individual. Mernit argues that, being character-driven, romantic comedies emphasize internal conflicts. The protagonist is emotionally inadequate until she or he finds the proper mate and becomes a more complete human being (2000: 16–17). For example, in The Truth About Cats and Dogs (1996) Abby (Janeane Garofalo), because she suffers from low self-esteem, sends her beautiful friend Noelle (Uma Thurman) to meet the handsome Brian (Ben Chaplin) rather than going herself. Finally Brian's growing attraction builds Abby's confidence, and she gains a partner who promotes her harmonious development. Motion pictures also strive to reveal interior, hidden conflicts. Rob Gordon (John Cusack) tells the audience of his secret desires in High Fidelity (2000), and the Jekyll-and-Hyde duality in The Nutty Professor (1963) portrays the split psyche of the scientist. Since the psychotherapy session has become familiar in the genre, this confessional mode has featured the expression of interior conflicts within the earnest Erica (Jill Clayburgh) in An Unmarried Woman (1978), the pathetic Ted (Ben Stiller) in There's Something About Mary (1998), and even the desperate Will in the sixteenth century of Shakespeare in Love. By now the therapy session has become a venue for internal conflicts and a staple source of humor in romantic comedy.

The conflict between repression and sexual desire has been central to romantic comedy and is a key to its internal struggles. As Kathleen Rowe writes, in comedy sex is part of an “overall attack on repression and [a] celebration of bodily pleasure” (1995: 104). Frequently this internal struggle becomes personified in the contending members of the couple. Whether it concerns the contest between the repressed David Huxley (Cary Grant) and the spontaneous Susan Vance (Katharine Hepburn) in Bringing Up Baby, the proper Jan Morrow (Doris Day) and the lecherous Brad Allen (Rock Hudson) in Pillow Talk (1959), or the contrasting sexual habits of Annie (Diane Keaton) and Alvy (Woody Allen) in Annie Hall, this conflict between sexual control and indulgence is a mainspring of romantic comedy. Frequently, institutional censorship, such as classical Hollywood's Production Code Administration, commonly known as “the Hays Office,” enforces repression, and so the genre has to work imaginatively to express desire through covert means. One pleasure of the romantic comedy arises from experiencing these discreet avenues to the erotic.

Warring gender cultures provoke men and women to exploit their suitors for personal advantage rather than embracing the bond of love. The internal conflict between exploitation and fellowship is portrayed in the mirrored opposition of the playboy and the golddigger, both of whom portray a negation of romance. On the one hand, the playboy's desire for sexual gratification without any emotional bond with his partner allows lust to prevail...