eBook - ePub

Mathematics in Ancient Greece

Tobias Dantzig

This is a test

- 192 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Mathematics in Ancient Greece

Tobias Dantzig

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

More than a history of mathematics, this lively book traces mathematical ideas and processes to their sources, stressing the methods used by the masters of the ancient world. Author Tobias Dantzig portrays the human story behind mathematics, showing how flashes of insight in the minds of certain gifted individuals helped mathematics take enormous forward strides. Dantzig demonstrates how the Greeks organized their precursors' melange of geometric maxims into an elegantly abstract deductive system. He also explains the ways in which some of the famous mathematical brainteasers of antiquity led to the development of whole new branches of mathematics.

A book that will both instruct and delight the mathematically minded, this volume is also a treat for readers interested in the history of science. Students and teachers of mathematics will particularly appreciate its unusual combination of human interest and sound scholarship.

A book that will both instruct and delight the mathematically minded, this volume is also a treat for readers interested in the history of science. Students and teachers of mathematics will particularly appreciate its unusual combination of human interest and sound scholarship.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Mathematics in Ancient Greece un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Mathematics in Ancient Greece de Tobias Dantzig en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Mathématiques y Histoire et philosophie des mathématiques. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

MathématiquesPART I

THE STAGE AND THE CAST

THE STAGE AND THE CAST

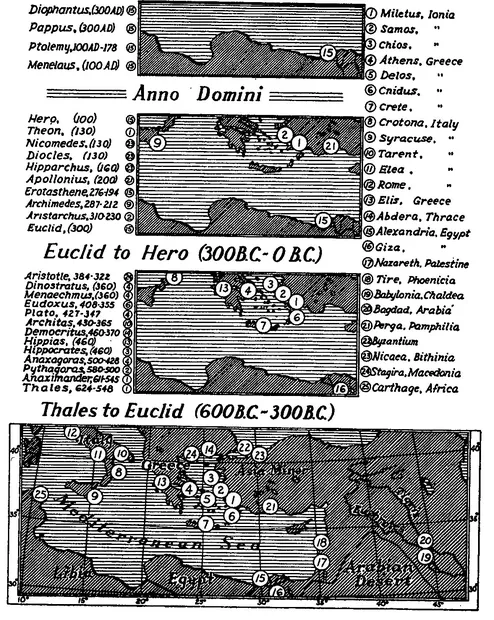

Figure 1

Chapter One

ON GREEKS AND GRECIANS

A dazzling light, a fearful storm, then unpenetrable darkness.

EVARISTE GALOIS

1

The stage on which were enacted the early episodes of the drama which I am about to unfold was Ancient Greece; the cast bore names unmistakably Greek; and the medium through which they conveyed their thoughts and deeds to their peers in culture was Greek, even though some of the records of these thoughts and deeds have passed through Latin and Arabic translations before reaching us. In these records we find the germs of theories and problems which have agitated the mathematical world ever since, and of which some remain unsolved to this day. We are told, indeed, that in mathematics most roads lead back to Hellas, and thus a book which makes any historical pretensions at all must needs begin with the question: Who were these Ancient Greeks?

The term conjures up in our minds a group of Aryan tribes, which had originally settled on the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula and adjacent islands of the Aegean Sea; then, spreading out in all directions, eventually reached the shores of Asia Minor, Lower Italy and the African littoral. The insular character of the land and its maritime activities encouraged independence and local rule; yet, dwelling as these people did at the very gateway of Europe, and menaced as they continually were by Oriental encroachment, they were often driven to “totalitarianism” as a means of self-preservation. Thus Ancient Greece became the proving ground of that struggle between oligarchy and democracy which has prevailed to this day; and as such we know it best.

But this is just one aspect of the complex pattern which the term evokes in our minds. In Ancient Greece stood the cradle of our culture: literature and philosophy, architecture and sculpture, in the various forms in which these arts are cultivated today, all had their origin in Greece. The songs of her poets, the works of her sculptors and the tracts of her philosophers are not mere monuments of a glory that was, but sources of study and inspiration today and, probably, for many centuries to come. Nor was the genius of these people limited to the arts and letters; their penetrating insight into the mysteries of number, form and extension had led them to develop to a high degree of perfection a discipline which they named mathematics, and which was destined to become both the model and the foundation of all sciences called exact.

This pattern becomes even more amazing when we contemplate that all this magnificent culture was erected in a few short centuries. We are told, indeed, that this great intellectual upheaval had reached its peak in the fifth century B.C.; that soon afterwards a general and rapid decline had set in, as though a fatal blow had been struck at the very roots of the mighty tree, a blow from which it never recovered; that after lingering on for a few more centuries, vainly endeavouring to live up to the grandeur of its past, it had finally succumbed to the coup de grâce administered by rising Rome.

2

Such is the picture of Ancient Greece as we perceive it through the thick historical fog of two thousand years. It is a perplexing picture, to say the least, for, as far as we know, nothing that ever happened before, or since, has even remotely resembled it. It is a picture of a people numerically insignificant, even when measured by standards of the Ancient World, which in the course of a few centuries erected a civilization of unprecedented magnitude, bequeathing to mankind for all time to come immortal treasures of literature, philosophy and mathematics. And the mystery becomes even more profound when we attempt —as is indeed our duty—to appraise this past in the light of the present. For the modern representatives of this ethnic group, far from exhibiting the acumen and finesse of their illustrious forebears, have contributed so little to the intellectual and artistic life of our time that it is difficult to conceive of any kinship between this Balkan people and the intellectual giants to whom our culture owes so much.

Is there anything wrong with this picture? Could it be that it is but another cliché, one of the many synthetic products of the diversified industry which passes today for liberal education? Well, this much is certain: in so far as the history of mathematics is concerned, this conception of Ancient Greece calls for a wholesale and drastic revision.

3

To begin with, the mathematical activity of Ancient Greece reached its peak during the glorious era of Euclid, Eratosthenes, Archimedes and Apollonius, a time when Greek letters, art and philosophy were already on the decline. There is a modern counterpart to this singular phenomenon. It was in the sixteenth century, the age of Cavalieri, Cardano, Galileo and Vieta, that mathematics was reborn; and the resurgence took place when the renaissance in arts and letters had already run its course, and the very names of Dante and da Vinci had become memories. Galileo was the central figure of that era, and the fact that he died one week before Newton’s birth has been the subject of much historical comment. It is as significant, perhaps, that Galileo was born in 1564, within a few months of the death of the last great representative of Italian renaissance, Michelangelo.

In the second place, while Roman contributions to mathematics were less than negligible, there is no evidence whatsoever that either the Republic or the early Empire had in any way hampered its progress. The eclipse of mathematics began with the Dark Ages, and the blackout did not end until the last Schoolman was shorn of the power to sway the mind of man.

4

Lastly, it was not Greece proper but its outposts in Asia Minor, in Lower Italy, in Africa that had contributed most to the development of mathematics. Some of these outposts were Greek conquests, others had come under Greek domination through alliance or trade. Moreover, since the Greeks had no Gestapo to protect their Aryan blood from pollution, racial intermingling was widespread, and there is no evidence that these misalliances were frowned upon by Greeks of pure strain.

To be sure, the Greeks did divide mankind into barbarians and Hellenes; yet, scions of barbarian families who had adopted Greek names and customs were viewed by Greeks as Hellenes. Thales of Miletus is a case in point. From all accounts he was of Phoenician origin, as was, indeed, Pythagoras; still, not only was Thales classed by his contemporaries as a Greek but proudly hailed by them as among the seven wisest Greeks. As to his own attitude, listen to the words which one biographer puts in his mouth: “For these three blessings I am grateful to Fortune: that I was born human and not a brute, a man and not a woman, a Greek and not a barbarian.”

In the centuries of Euclid and Archimedes Greek was the language of most educated men, whether they hailed from Athens, Syracuse, Alexandria or Perga. The significance of this will not escape the American observer familiar with the many melting pots strewn over this wide land. Could one assert that a man was of Anglo-Saxon blood because he was named Archibald or Percival and enjoyed a good command of English? Is it not equally naive to contend that a man who lived in the third century B.C. was racially a Greek because he called himself Apollonius and wrote in Greek?

The shores of the Mediterranean harboured many a melting pot into which Greeks and Etruscans, Phoenicians and Assyrians, Jews and Arabs were promiscuously cast. Who can tell today how the Aryans and Semites had been apportioned within these seething brews, or the Hamites, or the Ethiopians, for that matter? The motley mash passed into the sewers of history without leaving a trace of its composition behind it. The distilled essence alone remains, bottled in vessels which bear Greek inscriptions.

5

“A dazzling light, a fearful storm, then unpenetrable darkness.” So wrote Galois on the eve of his fatal duel; and if we did not know that he intended these words as a summary of his own short span of nineteen eventful years, we could take it as a description of the era of Hellenic mathematics.

What brought about this brilliant progress, and what caused the subsequent eclipse? I shall not add my own speculations to those of Taine and Comte, and Spencer, and Spengler and countless other historians of culture. This much is clear: mathematics flourished as long as freedom of thought prevailed; it decayed when creative joy gave way to blind faith and fanatical frenzy.

Chapter Two

THE FOUNDERS

To Thales . . . the primary question was not What do we know, but How do we know it, what evidence can we adduce in support of an explanation offered.

ARISTOTLE

1

Six centuries before the zero hour of history struck, there thrived on an Aegean shore of Asia Minor, not far from what today exists as Smyrna, a group of Greek settlements which went under the collective name of Ionia. It consisted of a dozen or so towns on the mainland, of which Miletus was the most prosperous, and of about as many islands, of which Samos and Chios were the largest. When measured by present-day standards, the territory was so small that if modern Smyrna were run by American realtors all that was once Ionia would be reduced to mere suburban “additions” to the “greater city.”

Here, within the span of about fifty years, were born the two “Founders” of mathematics, Thales of Miletus and Pythagoras of Samos. According to some of their biographers both were of Phoenician descent, which seems plausible enough since most of the coast of Asia Minor was at that time honeycombed with Phoenician colonies.

2

Who were these Phoenicians? We remember them chiefly today as the inventors of the phonetic script which was so vast an improvement over all the previous methods of recording experience that, in principle at least, it has undergone no significant change in the twenty-five hundred years which followed. The Greek alpha, beta, gamma, as well as the Hebrew aleph, beth, gimel are but adaptations of the Phoenician symbols for these letters.

And yet, having bestowed upon mankind this marvellous method of recording events, the Phoenicians left practically no records of their own, and what little we know of them today we owe to Greek or Hebrew sources. They were a Semitic tribe, and their homeland was what we call today Syria. As Canaanites, Moabites, Sidonians, they fill many a page of the Bible. Apparently, whenever they did not engage the Hebrews in mortal combat they fought them with subtle propaganda, inducing the fickle sons of Israel to abandon Jehovah for Baal and other more tangible gods.

The Greeks knew the Phoenicians under a different guise. They spoke of them as crafty merchants and skilled navigators, and called them “Phoenixes,” i.e., red, because of the ruddy complexions which the Mediterranean sun and winds had imparted to these ancient mariners. For, the Phoenicians roved that “landlocked ocean of yore” from end to end, exchanging wares and founding colonies, such as ill-fated Carthage, or Syracuse, the birthplace of Archimedes, who, reputedly, was also of Phoenician descent.

3

I said that Thales was classed by the Greeks as one of the Seven Sages. Indeed, he was the only mathematician so honoured, and it was his reputed political sagacity and not his mathematical achievements that had earned him the title. Because of this distinction, Thales was the subject of many historical studies, with the result that much had been written on his life and deeds. Of what value are these biographical accounts? Here are some highlights from which you can draw your own conclusion.

We are told by one of these commentators that Thales was so keen an observer that nothing would escape his alert attention; yet, according to another, he was so absent-minded that even as a grown-up man h...

Índice

- DOVER BOOKS ON MATHEMATICS

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgment

- Table of Contents

- PART I - THE STAGE AND THE CAST

- PART II - AN ANTHOLOGY OF THE GREEK BEQUEST

- EPILOGUE

- INDEX

- A CATALOG OF SELECTED DOVER BOOKS IN ALL FIELDS OF INTEREST

Estilos de citas para Mathematics in Ancient Greece

APA 6 Citation

Dantzig, T. (2012). Mathematics in Ancient Greece ([edition unavailable]). Dover Publications. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/111018/mathematics-in-ancient-greece-pdf (Original work published 2012)

Chicago Citation

Dantzig, Tobias. (2012) 2012. Mathematics in Ancient Greece. [Edition unavailable]. Dover Publications. https://www.perlego.com/book/111018/mathematics-in-ancient-greece-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Dantzig, T. (2012) Mathematics in Ancient Greece. [edition unavailable]. Dover Publications. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/111018/mathematics-in-ancient-greece-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Dantzig, Tobias. Mathematics in Ancient Greece. [edition unavailable]. Dover Publications, 2012. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.