eBook - ePub

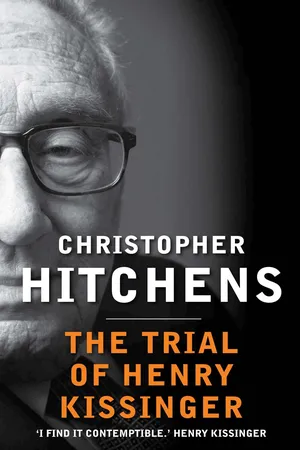

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

Christopher Hitchens

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

Christopher Hitchens

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Trial of Henry Kissinger un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Trial of Henry Kissinger de Christopher Hitchens en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politics & International Relations y Political Biographies. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

Politics & International RelationsCategoría

Political BiographiesContents

Foreword to the Twelve Edition

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Preface

Introduction

1. Curtain-Raiser: The Secret of ’68

2. Indochina

3. A Sample of Cases: Kissinger’s War Crimes in Indochina

4. Bangladesh: One Genocide, One Coup and One Assassination

5. Chile

6. An Afterword on Chile

7. Cyprus

8. East Timor

9. A “Wet Job” in Washington?

10. Afterword: The Profit Margin

11. Law and Justice

Appendix I: A Fragrant Fragment

Appendix II: The Demetracopoulos Letter

Acknowledgments

Index

Foreword to the Twelve Edition

It was not long into our first conversation with Hitch—can it be thirty years ago?—that the unctuous presence of Henry Kissinger made itself felt. The year must have been 1981, and my wife, Angélica, and I were in exile from a Chile terrorized by General Augusto Pinochet and Christopher had just arrived in Washington, DC, to write for The Nation, after a recent stint as a foreign correspondent on the luckless island of Cyprus. Cyprus and Chile, two countries joined in misfortune and sorrow and betrayal, hounded by the same man, the same “statesman,” the same war criminal who had been Nixon’s secretary of state.

I can’t recall exactly the place where Angélica and I met Hitch—it may have been Barbara Ehrenreich’s apartment or at the always welcoming house of Saul Landau—nor can I recollect the exact contours of our almost simultaneous diatribe against Kissinger that evening, but I like to think that in some glorious recess of Christopher’s febrile and extraordinary brain, he was already planning this book, starting to put on trial the despoiler of Chile and Cyprus. And let’s not forget Cambodia and Vietnam and East Timor and the Kurds—the Kurds, above all let us not ever forget the Kurds, because Christopher never did.

Over the years, more indictments like those of that first evening were sprinkled through our long and plentiful and often contentious friendship. Like true friends, we did not agree on everything, but Kissinger was always there to remind us of how deep our desire for justice ran; our conviction, his and mine, that if one could not physically bring a man responsible for genocide before a tribunal, there was always the written word to pin him to the wall and eviscerate his impunity. Neither of us thought—at least I didn’t—that such a trial in the world of realpolitik and fawning media and obsequious politicians would ever be possible.

General Pinochet’s arrest in London in 1998 changed that. That a former head of state could be subjected to universal jurisdiction (a term that Christopher highlights in his opening remarks of this book) for crimes against humanity, that the decision to find sufficient reasons to extradite the former Chilean dictator to Spain had been approved by the several courts in London and confirmed by the Law Lords (an equivalent to the US Supreme Court), was undoubtedly the trigger that led to The Trial of Henry Kissinger being written. If Pinochet, then why not Kissinger? Why not anyone whose dossier proved a conscious and systematic involvement in egregious human rights violations, no matter how influential that person might be? Or should the law only be applied to a land like Chile, with no nuclear weapons or bases strewn around the world, and not the United States, flexing its power and muscle?

The book itself is vintage Hitchens, in the tradition of Thomas Paine, one of his heroes: incisive, ironic, chock full of information, contemptuous of what the pundits might think, redolent with indignation and choice adjectives. But most crucial, what I now read behind the rant, many years later, is the same thing that struck me about Christopher in that very first conversation we had.

A topic that Hitch kept coming back to on that night in 1981, as he would often during the years ahead, was that of the missing of Chile, the desaparecidos, men and women abducted from the streets or their homes by the secret police and never heard of again, absent from the world as if they had never been born. We discussed at some length (it was my obsession then and still is) how this atrocity, along with affecting the bodies of those who had been kidnapped, devastated the lives of the relatives who could not find their beloved, who could not even bury their corpses or mourn an uncertain death.

Hitch’s interest in this tragedy was motivated, naturally, by something that would define a life crusading for the rights of those who were neglected and forgotten and postponed. Especially by the mainstream media. And it was Cyprus, which Christopher mentioned to me and Angélica during that first interminable and deep conversation, gesturing toward his own then wife, Eleni, a Greek Cypriot whom Hitch had met while covering the Turkish invasion of the island. “Eleni’s people also have desaparecidos,” was, if I am not mistaken, the stark way in which he introduced the theme. And not long thereafter, he called me up at our home and invited us to the opening of an exhibition of photographs about the plight of the Cypriot refugees, which emphasized in particular the calamity of those who were still missing after the war. When Angélica and I arrived for the inauguration (it was at an out-of-the-way place, a small gallery, I think), there was hardly a soul there—an instance of inattention that outraged Hitch and made him even more determined to highlight the invisible sorrow that was visiting a people he had fallen in love with. Years later he would recall, both publicly and privately, how moved he was that we had taken the time to share that experience of exile and sorrow and struggle when so many others simply didn’t give a damn.

But he got that one wrong. I wasn’t the one to be thanked for having been present at that exhibition. Hitch was the one to be thanked for caring enough, for helping me understand (as he does in this book) how the catastrophe of Chile was linked in so many ways to the disasters assailing other areas of the earth, how we need to hold those who inflicted the damage accountable in as many ways as we possibly can. In that invitation to see the photos, as in this book that now sees the light of day again, as in a variety of other instances, he expanded the universe, he made the connections. He was always ready to open doors and windows that nobody else dared to even notice, and he did so, invariably with unfailing wit and grace and a sort of penetrating lyricism, provoking us till we paid attention. He simply refused to remain silent.

That is what really pulses through this book.

The victims. So many who have not lived to see Kissinger and others like him put on trial. So many who are represented in the sweet tirade against a war criminal who walks in freedom but who is always, thanks to books like these, looking over his shoulder.

Wondering if the Hitch will get him.

Because a year after this book was published, the heroic Kissinger was sojourning at (where else?) the Ritz Hotel in Paris when he was summoned to appear before French judge Roger Le Loire, who wanted to question the “elder statesman” about his involvement in Operation Condor (and whether he knew anything about five French nationals who had been “disappeared” during the Pinochet dictatorship). Rather than take the occasion to clear his name, Kissinger fled that very night. And he has never been able to sleep abroad with any semblance of serenity ever since: more indictments followed, from Spain, from Argentina and Uruguay, and even a civil suit in Washington, DC.

Oh yes, maybe the Hitch will indeed get him.

True, Christopher did not believe in ghosts or spirits or the afterlife.

But indulge me, comrade. Accept that while books like these are alive, and while your innumerable allies continue the quest for justice, well, perhaps you can smile at the thought that we will refuse to let you become one more desaparecido.

ARIEL DORFMAN

February 2012

Preface to the Paperback Edition

When this little book first appeared, in what may now seem the prehistoric spring of 2001, it attracted a certain amount of derision in some quarters, and on two grounds. A number of reviewers flatly declined to believe that the evidence presented against Henry Kissinger could be true. Others, willing to credit at least the veracity of the official documents, nonetheless scoffed at the mere idea of bringing such a mighty figure within the orbit of the law.

It says nothing for the author, but a great deal about the subject, to be able to report that the lapse of just one year has brought important and incriminating new disclosures and seen significant new developments. To begin with the disclosures, then, one might instance fresh and conclusive evidence under four of the headings originally discussed here: Indochina, Latin America, East Timor and Washington, DC. And, to follow on with the legal developments, one can now cite important proceedings brought against Kissinger in four democratic countries, including his own. I hope I will not seem to boast if I say that most of these disclosures and initiatives were foreshadowed in the first version of this book. At any rate, they now appear below and any reader may judge by comparison with the unaltered original text.

Indochina

Further material has come to light about both the origins and the conclusion of this terrible episode in American and Asian history. The publication of Larry Berman’s No Peace, No Honor: Nixon, Kissinger and Betrayal in Vietnam in early 2001 provided further evidence of the secret and illegal diplomacy conducted by Nixon and his associates in the fall of 1968, and discussed on pages 1–21 here as well as in my appendix on page 205. Indeed, it can now be safely said that the record of this disgusting scandal has become, so to speak, a part of the official and recognized record, rather as President Johnson’s original provocation in the Gulf of Tonkin is now generally called by its right name. (In his edition of President Johnson’s private papers and conversations in the fall of 2001, Professor Michael Beschloss produced first-hand and direct proof that Johnson himself knew at the time that he was lying to the Congress and the world about the episode.)

As for the expiring moments of that hideous war, the month of May 2001 saw the publication of an extraordinary book, The Last Battle: The Mayaguez Incident and the End of the Vietnam War. Written by Ralph Wetterhahn, a Vietnam veteran who had decided to stay with the subject, the book establishes beyond doubt by the use of contemporary documents and later interviews that:

a) The crew of the Mayaguez were never held on Koh Tang island, the island that was invaded by the United States Marine Corps.

b) The Cambodians had announced that they intended to return the vessel, and had indeed done so even as the bombardment of Cambodian territory was continuing. During that time, the crew was being held on quite another island, named Rong Sam Lem. The statements of Ford and Kissinger, claiming credit for the eventual release and attributing it to the intervention on the wrong island, were knowingly false.

c) American casualties were larger than has ever been admitted: twenty-three men were pointlessly sacrificed in a helicopter crash in Thailand that was never acknowledged as part of the operation. Thus, a total of sixty-four servicemen were sacrificed to “free” forty sailors who had already been let go, and who were not and had never been at the advertised location.

d) As a result of the official panic and confusion, three Marines were left behind alive on Koh Tang island, and later captured and murdered by the Khmer Rouge. The names of Lance Corporal Joseph Hargrove, Pfc Gary Hall and Pvt Danny Marshall do not appear on any memorial, let alone the Vietnam Veterans’ wall (see my page 31). For a long time, their names had no official existence at all, and this “denial” might have succeeded indefinitely were it not for Mr. Wetterhahn’s efforts.

Kissinger was the crucial figure at all stages of this crime and cover-up, arguing at the onset of the crisis that B-52 bombers should at once (and again) be l...