![]()

Pictures do lie!

PETER GAY

1

Imperial Frames

DAGUERREOTYPES

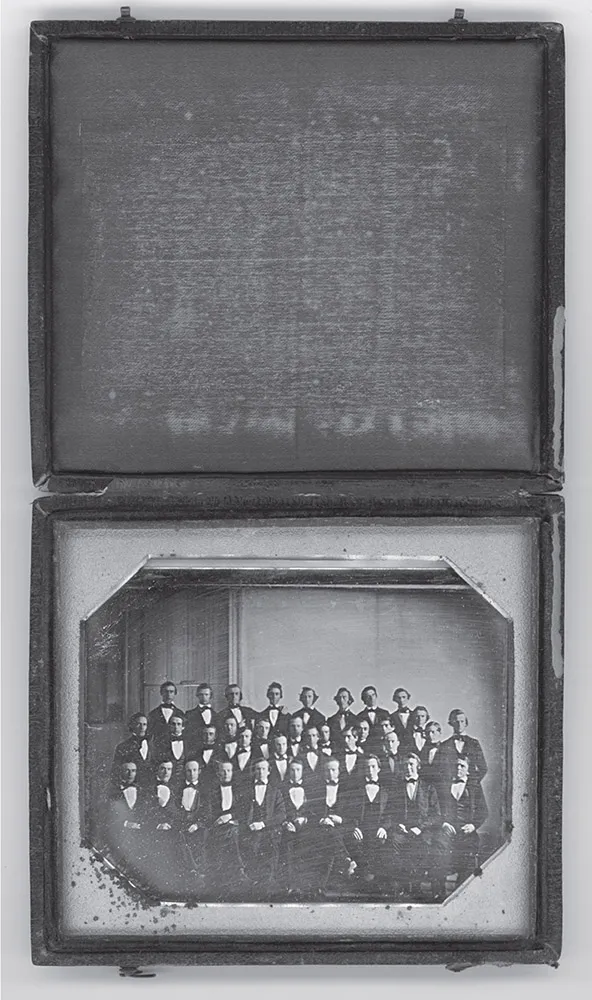

An untitled daguerreotype (fig. 1.1) is perhaps the oldest surviving class photograph in the United States, possibly the world. Housed in the Princeton University Archives and set in a now slightly blemished frame and gilt mat, it shows a sober assemblage of formally dressed men, probably members of the College of New Jersey Class of 1843 and a few of their teachers.1 Depicting a group of students who jointly belong to a particular university class and who share a graduation year in common, the image adheres to conventions of group portraiture commonly employed in paintings of guilds, army units, or clubs. It presents viewers with a photographic portrait of an institutional group in which individual personalities and differences are subsumed within a collective assemblage. It highlights standardized clothing, conformity of appearance and posture, and a camera-facing multirow lineup—group features probably arranged by the photographer to serve institutional wishes, and enforced by the students’ most immediate institutional disciplining powers, the teachers.

The practice of photographing school classes and student groups was established during photography’s earliest years, as evidenced by the many surviving daguerreotypes of school groups made in the 1850s in the United States. The portrait of students from the Emerson School for Girls in Boston in the early 1850s (fig. 1.2) is especially noteworthy for its excellence as a school photo employing the daguerreotype technology.

Made by photographers hired by the institution, these and other daguerreotypes of school assemblages certify the constitution of a class or grade of students at a particular moment in time. As daguerreotypes, however, they are restricted by the constraints of the medium in which they were created. All were produced on mirror-like reflective polished silver—material easily tarnished in open light and air. They could not, and cannot, be displayed unshielded for very long without sustaining corrosive damage and are thus viewable only in a light-controlled space. Each is a singular photographic product—a one-of-a-kind image that cannot be replicated and shared. Daguerreotypes are dedicated to the needs of the institution that commissioned their making, and to that institution’s vision and recording of its own history, rather than to the personal and collective memories of the students in the images or those of their families.

The culture of photographic images, however, changed dramatically in the early 1850s. The development of the collodion/albumen glass-plate process, large-format printing, sharp detail, tonal variation, and, most revolutionary of all, image reproducibility made photographic technology more broadly accessible.2 These technological innovations were profoundly influential in the taking and dissemination of school photos. Very quickly, class photos of children and young adults were recognized as desirable reproducible objects. Professional photographers, perceiving their potentially more widespread commercial appeal, began to promote and feature them within their repertoire of offerings. School photos could now be sold and archived not only for exhibition as sources of institutional history and pride but also as mementos of individual and group achievement for all portrayed students and for their families.

FIGURE 1.1. Group portrait of thirty-five men, thought to be members of the College of New Jersey Class of 1843 with some faculty. Quarter plate daguerreotype. Photo possibly by George Prosch. (Princeton University Archives)

FIGURE 1.2. Class portrait of the Emerson School for Girls, Boston, ca. 1850. George Barrell Emerson (1797–1881), a staunch advocate of women’s education, founded his own school in response to the gender segregation of the English Classical School, where he had been headmaster. Daguerrotype by Albert Sands Southworth. (Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of I. N. Phelps Stokes, Edward S. Hawes, Alice Mary Hawes, and Marion Augusta Hawes, 1937. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.)

The institutional gaze shaping school pictures adhered to them through these technical and social transformations, displacing individuality ever more definitively with a broader, more homogeneous, group identity. Nevertheless, Frederick Douglass, who escaped from slavery and became a prominent abolitionist, social reformer, orator, and writer, saw photographic reproducibility as a means of individuation and an instrument of liberation. Said to be the most photographed man of the nineteenth century, he was exceedingly deliberate about his visual image. In his famous 1850s speeches about photography—speeches given even as the medium was in the process of being developed—Douglass stresses the democratic potentials of this new technology through which “the humblest servant girl can now see a likeness of herself, such as the wealth of kings itself could not purchase fifty years ago.”3 For Douglass, photographic reproducibility enables the possibility of a broad-based, more egalitarian production of individual and group images—a possibility of representation unique to humans. As he sees it, in the aftermath of slavery, the capacity to create images is a condition of freedom, one able to help reorient the United States’ vision of progress and a free, democratic future. In an illuminating close reading of the two versions of Douglass’s speech, Laura Wexler argues that Douglass set up his own numerous photographic studio portraits to cast himself as a “revenant” from the social death of slavery.4

Indeed, later technical developments, such as the Kodak Brownie camera’s invention in the late 1880s and popularization in the twentieth century, enabled many families and children—for the most part, those rising economically into the middle class and able to afford to take and develop photographs—to become image makers themselves. Though they would not generally take class or large group photos, they could reimagine institutional framings, creating more intimate, and thus more resistant, representations of school and class, as well as of civil life. Like Douglass, they could use the evidentiary truth value attributed to photography to create positive self-images that would contest prejudicial or demeaning representations of certain individuals and social groups.

In contrast to this view of photography’s democratic potential, Walter Benjamin discusses the loss of authenticity and what he terms “aura” as a by-product of a work of art’s reproducibility. While the portrait “was the focal point of early photography,” he argues in his classic 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” mechanically reproducible photographs become instrumental: they serve as “standard evidence for historical occurrences and acquire a hidden political significance.”5 Reproducibility, combined with instrumentality, inaugurates the modern subject, one who lacks the aura of individuality, fading into the undifferentiated masses. The modern subject, Benjamin suggests, is the subject of mechanical surveillance and close examination. His (or her) actions and movements can be more clearly discernible to the mechanical camera gaze than to the human eye: “The camera introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses.”6 One might then add that the camera, as an instrument of state institutions and their determinative surveillance, has the potential to influence, shape, and transform the objects of its gaze. These differing views of photography’s role in shaping social subjects are especially relevant to the work of school photos throughout the history of public education.

HIERARCHY, DIFFERENCE, SCHOOLING, AND PHOTOGRAPHY

Technical innovations in photography in the second half of the nineteenth century coincided with the development and growth of public education in the United States and in Western Europe, and with efforts to train populations for the economic, social, and political demands of a rapidly expanding capitalist world. But they also coincided with two related, and extremely consequential, nineteenth- and twentieth-century sociopolitical processes undertaken by civil and imperial authorities throughout Europe and the Euro-American worlds.

The first process attempted to realize the political desire (need is perhaps the more accurate term) on the part of imperial authorities in pre–World War I Europe to integrate far-flung and culturally diverse subjects and colonized people into more effectively consolidated, centralized, and hence controllable imperial states. The second process expressed a vigorous intent by dominant, white, political, civil, and religious/missionary authorities to transform colonized and subordinated groups into culturally similar versions of themselves so that those groups might effectively serve the imperial mission.

Both of these processes, involving cultural transformation and social and political integration, were ideologically assimilationist. Both challenged the late-nineteenth-century growth and increasing dominance of a new Euro-American pseudoscientific racism that maintained that subordinated, racialized “others” were biologically/genetically—and thus unalterably—inferior to Euro-American whites. But while not explicitly racist in a biological/genetic sense, the assimilationist changes these civil and imperial agencies attempted to engineer in Jews, black and Native Americans, and colonized people in Africa and Australasia were based on a racially coded cultural chauvinism that rested on racialized notions about the contrast between what dominant whites termed “savagery” and “civilization,” “heathendom” and “Christianity.” Accordingly, in their own descriptive terms, “primitive,” “barbaric,” “backward” ways of living, thinking, and worshiping—which they considered culturally induced, not biologically inherent, but associated with “less enlightened” or “less evolved” nonwhite and non-Christian people—needed to be erased and replaced by what they firmly regarded as superior, white, Euro-American and Christian ones.7 If this eradication and substitution was not achievable within the older generations through so-called civilized education, hard work, and disciplined control, then it had to be carried out within their children and grandchildren.

“The kind of education they are in need of is one that will habituate them to the customs and advantages of a civilized life . . . and . . . cause them to look with feelings of repugnance on their native state,” stressed George Wilson, a commentator on Indian affairs, in an 1882 Atlantic Monthly article about the education of Indians in the United States.8 “Kill the Indian, and Save the Man,” concurred Captain Richard Henry Pratt, the founding superintendent of the Carlisle Indian School, in a publicly presented and much-quoted lecture in which he argued for Indian youths’ “disciplined” assimilation into “civilized” Anglo-America. “It is a great mistake to think that the Indian is born an inevitable savage,” he noted:

He is born a blank, like the rest of us. Left in the surroundings of savagery, he grows to possess a savage language, superstition, and life. We, left in the surroundings of civilization, grow to possess a civilized language, life, and purpose. Transfer the infant white to the savage surroundings, he will grow to possess a savage language, superstition, and habit. Transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of civilization, and he will grow to possess a civilized language and habit.9

State-certified schooling came to play a key role in furthering these culturally assimilationist goals in Euro-American imperial realms. It did so through two structurally divergent approaches. The first, integrated education, incorporated students from different ethnic, national, and religious backgrounds, including children affiliated with dominant groups, in joint classrooms. The second, segregated education, predominantly used with colonized and minority or subordinated populations, could serve similar transformative goals by educating them apart from Christian whites. Both integrated and segregated education, however, shared a common purpose: to induce students to become loyal supporters, if not agents, of the ruling state. And they were to be induced to do so without challenging hierarchies that maintained white Euro-American social and economic supremacy.

Photography, especially school photography, became a central technology to visually publicize and certify the assimilationist project’s institutional efficacy and cultural erasures. School photos assumed this institutional function both in integrated schools in Europe and in segregated schools in colonial Africa, Asia, Australia, Canada, and the United States. In both cases, class photos probed the visibility, and thus also the invisibility, of social differences, especially racialized differences. As Coco Fusco writes, “Rather than recording the existence of race, photography produced race as a visualizable fact.”10 We might specify that school photos schooled students and communities to “see,” and thus to reify, difference as racialized.

And yet, as group images depicting multiple persons with different individual histories, psychologies, and attitudes, school photos also became remarkably informative documents. Within them, the variegated textures of assimilationism and induced cultural change could be investigated both from the perspective of the institutions perpetrating them, and from that of their subjects. By eliciting a “civil gaze” that connected photographed subjects and their viewers as members of a shared citizenry, they could indicate not only how assimilationism fostered social cohabitation among different groups, but also how such cohabitation might turn into oppression, persecution, and radical separation. Indeed, it is through the “civil gaze” they prompt that school photos become privileged objects in a study of the contradictions and mutabilities that structure the process of assimilation. In this sense, each photo can be studied as a snapshot of a moment in this process that reveals its pushes and pulls, assents and dissents, gains and losses. It can thus disclose what Sara Blair has so usefully cha...