eBook - ePub

Children's Picturebooks Second Edition

The Art of Visual Storytelling

Martin Salisbury, Morag Styles

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Children's Picturebooks Second Edition

The Art of Visual Storytelling

Martin Salisbury, Morag Styles

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Children's picturebooks are the very first books we encounter and play a major role in introducing us to both art and language. But what does it take to create a successful picturebook for children? This revised edition of a bestselling title carries invaluable insight into a highly productive, dynamic sector of the publishing world. Featuring interviews with leading illustrators and publishers from across the world, it remains essential reading for students and aspiring children's book illustrators and writers.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Children's Picturebooks Second Edition un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Children's Picturebooks Second Edition de Martin Salisbury, Morag Styles en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Design y Graphic Design. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

DesignCategoría

Graphic DesignChapter 1

P ictorial storytelling can be traced as far back as the earliest paintings on cave walls, which would have been gazed upon and enjoyed by people of all ages. Some examples in France and Spain may be 30,000 to 60,000 years old. We can only speculate as to the purpose or meaning of this art, but the images would have been one of the most important means of communication at the time. The tombs of ancient Egypt and the walls of Pompeii also provide evidence of our long-standing need to describe and narrate visually.

The oldest surviving ‘illustrated book’ is said to be an Egyptian papyrus roll from around 1980 B C. The pure chance of its survival, buried in sand, suggests that such perishable artefacts had been around for longer. David Bland’s scholarly 1958 work, A History of Book Illustration (Faber & Faber), quotes Leonardo da Vinci:

And you who wish to represent by words the form of man and all the aspects of his membrification, relinquish that idea. For the more minutely you describe, the more you will confine the mind of the reader, and the more you will keep him from the knowledge of the thing described. And so it is necessary to draw and to describe.

Who better to introduce us to the historical background to the modern picturebook?

The printing of books from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century

The invention of printing in the fifteenth century meant that education in the West began to become available to more than just the wealthy few who had access to hand-produced literature. Most scholars agree that printing, like paper, originated in China. Block printing had certainly been around for a while, but in Europe it was the invention of movable type by Johannes Gutenberg in the 1430s that opened the way for viable mass publishing.

Ulrich Boner’s Der Edelstein (1461) is often cited as the first example of a book with type and image printed together. Comenius’ Orbis Sensualium Pictus (The Visible World), published in Nuremberg in 1658, is generally seen as the first children’s picturebook, in the sense that it was a book of pictures designed for children to read. It was not until much later that the precursors of the picturebook as we know it began to emerge. The chapbooks of the sixteenth to the nineteenth century were cheaply produced, illustrated with crudely prepared and printed woodcuts, and were hawked around the countryside by pedlars for an audience with often limited funds and levels of literacy and funds. The relationship between words and pictures here was often a tenuous and largely decorative one.

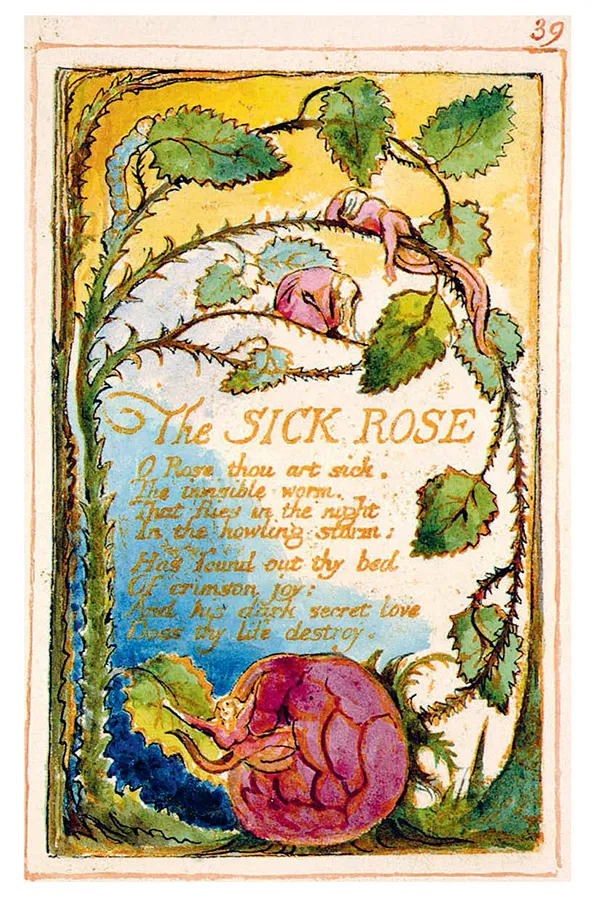

The inspirational painter and poet William Blake can, perhaps, be seen as the first to experiment with the symbiotic relationship between word and image, at least in the sense of their visual arrangement. Blake produced Songs of Innocence in 1789, printing and publishing the book himself. His idiosyncratic, visionary visual style was totally original, owing little to anything happening in the visual arts at that time. Brian Alderson, in his book Sing a Song for Sixpence: The English Picture-Book Tradition and Randolph Caldecott (Cambridge University Press, 1986), declares:

So it comes about that the first masterpiece of English children’s literature, which is also the first great original picture book, stems from an impulse to integrate words and images within a single linear whole.

Thomas Bewick’s emergence in the late eighteenth century must be mentioned in relation to the general development of book illustration because of his achievement in elevating the art of wood engraving to a completely new level. His technical skills – engraving in fine line on the end grain of dense woods such as box – combined with an intense interest in the natural world produced results that took the process far beyond a merely reprographic role. The central character of one of the earliest depictions of a believable child in literature, in Chapter 1 of Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (first published in 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co), finds comfort in looking at Bewick’s artwork.

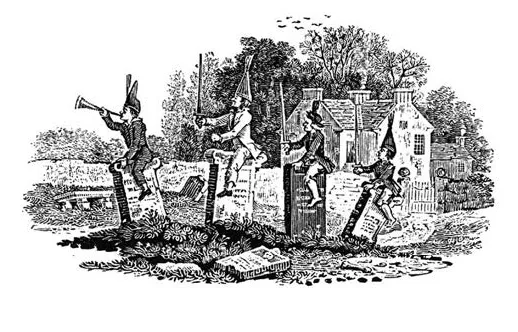

The term ‘chapbook’ derives from ‘chapman’, the word used to describe a pedlar who hawked the books around the country along with his other wares. The pocket-sized books contained woodcut prints such as this one, rather randomly related to a text.

Thomas Bewick’s engravings introduced new levels of technique and an earthy anecdotal charm to the world of book illustration.

William Blake’s integration of words and images within a pictorial whole is often seen as an early forerunner of today’s picturebook.

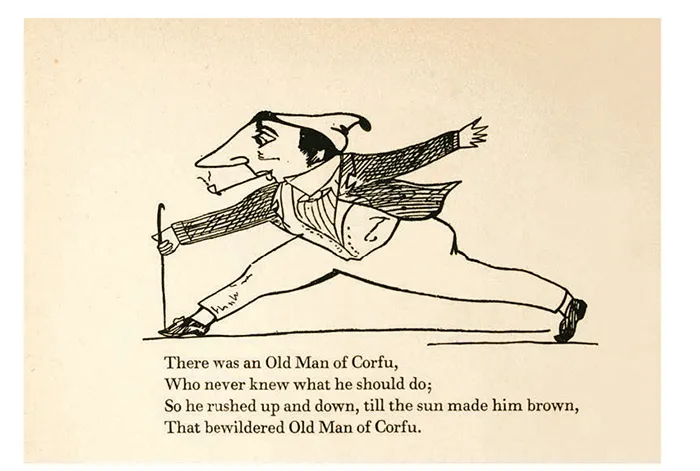

Edward Lear’s illustrations to his A Book of Nonsense were in stark contrast to his topographical travel paintings. As a travelling watercolourist, Lear depicted panoramic landscapes with subtle washes. To accompany his nonsense limericks he created playfully anarchic line drawings that perfectly echo his words.

Colour printing in the nineteenth century

Until the 1830s, colour was usually added by hand until a process for printing colour from woodblocks was invented, independently of each other, by George Baxter and Charles Knight. Baxter patented his ‘Baxter process’, which combined an intaglio keyplate with multiple woodblocks, in 1835. An Austrian, Aloysius Senefelder, had invented the principle of lithography (which is the basis of all mass printing today) in the late eighteenth century, but it would be a while before the process was in regular use.

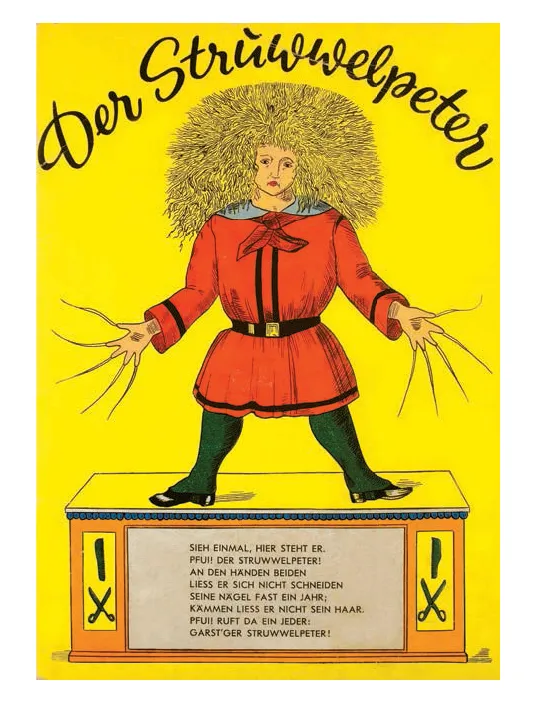

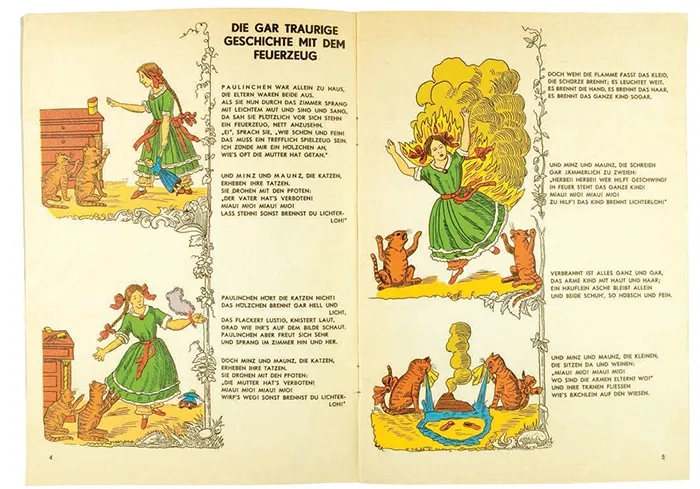

One of the more direct influences on the modern picturebook is Der Struwwelpeter by Heinrich Hoffmann. Much has been made of the levels of cruelty and violence in Hoffmann’s cautionary tales of the ghastly consequences of misbehaviour, but they have stood the test of time in every sense, having been reinterpreted through many and varying media. The original title, Funny Stories and Droll Pictures, hints at a playful, even ironic, intent on the part of the author that presages the contemporary postmodern picturebook. Hoffmann’s famous book reached England from Germany in around 1848, and is comparable in many ways to Edward Lear’s A Book of Nonsense, which had been published a few years before. But while there are stylistic parallels, heightened by the printing processes of the time, Lear’s delightfully anarchic visual and verbal texts show no inclination to moralize, or indeed to conform, to any rules of linear narrative. If any meaning can be ascribed in the traditional sense, it may be the championing of the outsider, perhaps as a consequence of Lear’s recurrent bouts of depression.

The iconic status of Hoffmann’s Der Struwwelpeter is testament to its originality and radical nature.

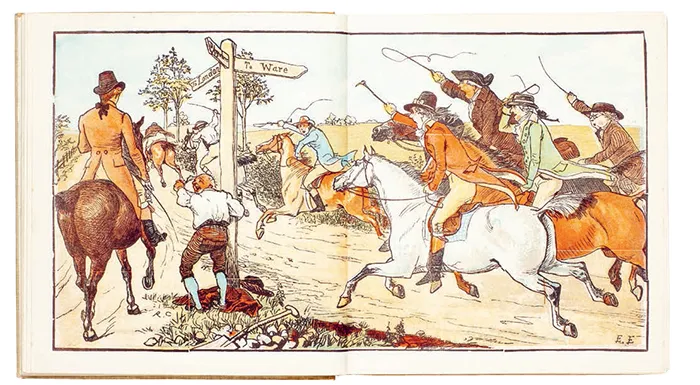

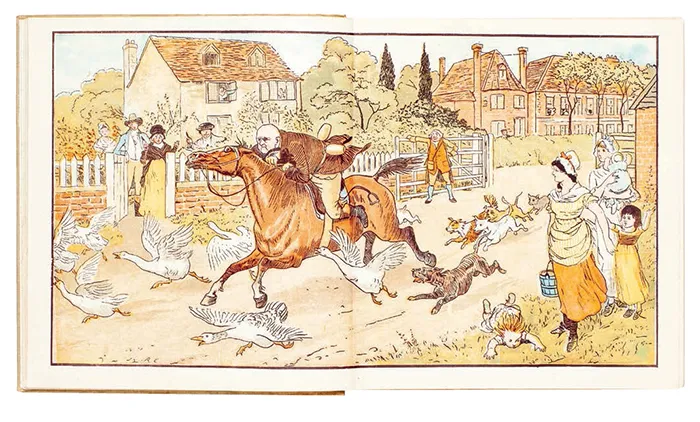

Randolph Caldecott’s illustrations to The Diverting History of John Gilpin were published in 1878 though William Cowper’s ballad of the draper and the runaway horse had first appeared in print in 1782.

The birth of the modern picturebook in the late nineteenth century

It was at exactly the time of the publication of A Book of Nonsense that the most important figure in the picturebook’s evolution was born. Randolph Caldecott is generally acknowledged to be the father of the picturebook. Maurice Sendak, perhaps the greatest author of visual literature of our time, identifies Caldecott’s place in the picturebook pantheon. Writing in his book of essays, Caldecott & Co: Notes on Books and Pictures (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1988), he explains:

Caldecott’s work heralds the beginning of the modern picture book. He devised an ingenious juxtaposition of picture and word, a counterpoint that never happened before. Words are left out – but the picture says it. Pictures are left out – but the word says it. In short, it is the invention of the picture book.

This ‘rhythmic syncopation’, as Sendak describes it, was a radical departure from the relationship between the visual and verbal texts that had prevailed hitherto. In stories such as A Frog he would A-wooing Go (George Routledge & Sons, 1883) and Come Lasses and Lads (George Routledge & Sons, 1884), a pictorial subtext emerges that expands rather than merely duplicates or decorates the narrative content as conveyed by the written word. Caldecott’s superlative draughtsmanship, of course, seals his position in the history of picturebooks. The books were published as Randolph Caldecott’s Picture Books and Caldecott is thought to have been the first artist to negotiate a royalty payment (one penny per book) rather than a flat fee.

Caldecott tends to be bracketed with two other artists of the mid to late Victorian era: Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway. Although their work is in many ways very different from Caldecott’s, it is linked to his picturebooks by the key role played in its dissemination by the printer Edmund Evans. At this time, the distinction between printer and publisher had not really emerged. Evans brought a sophisticated eye to the works of these three artists and the best way to do justice to them in mass reproduction. The garish and oily effects of the chromolithographic processes that prevailed were not sympathetic or appealing to the better artists of the day. Evans, an artist himself, demonstrated that colour printing with wood could be subtle, effective and cheap. He pioneered the application of photographic processes to the preparation of woodblocks.

Walter Crane’s work demonstrates a preoccupation with the visual, rather than conceptual, relationship between word and image, and is consequently much more static and less fluent than that of Caldecott. It has also come to embody in many ways the Arts and Crafts style. Crane’s comments in his Reminiscences of 1907 on Evans’ more ‘tasteful’ approach to printing are revealing: ‘… but it was not without protest from the publishers who thought the raw, coarse colours and vulgar designs usually current appealed to a larger public, and therefore paid better…’

Such tensions between perceptions of public taste/ commercial potential and artistic integrity are still hot topics of debate between artist and publisher today.

Kate Greenaway’s fragrant, innocent world of Under the Window (George Routledge & Sons, 1879), with its distinctive, prettily dressed children who look like miniature adults, has survived the damnation of faint praise from contemporary and modern critics alike and her popularity endures. Alderson tells us that we, ‘… should not lose sight of the freshness of the little sub-fe...