![]()

1

Housing tenure and an ageing society

Introduction

Australia, like all developed economies, is experiencing a significant demographic shift. The proportion of the population that is aged 65 years and older has increased substantially and is continuing to do so. However, it is doing so in the context of one of the world’s most expensive housing markets (Cox and Pavletich 2016; Janda 2015; Scatigna et al. 2014). The demographic shift, combined with the nature of Australia’s housing market, potentially has major ramifications. In 1971, 8.3% of Australia’s population was 65 years and older, which had risen to 11.8% by 1994 and to 14.7% by June 2014 (ABS 2012a, 2014; AIHW 2014). If current trends continue, it is estimated that, by 2034–35, 19.5% of the population will be 65 and over (Australian Government 2015:12). Globally, there is much debate about the implications of an ageing society and the capacity of governments to sustain the Age Pension and the capacity of the health system (Australian Government 2015; Biggs et al. 2007; Productivity Commission 2013). At the end of 2013, the influential think tank, The Grattan Institute, issued a report that advocated the Australian Government increase the age of access to the Age Pension and superannuation (the legislated private pension scheme to which all employers and employees have to contribute) to 70. The report argued that this measure ‘is one of the most economically attractive choices to improve budgets in the medium term’ (Daley et al. 2013: 29). At the same time, a report titled An Ageing Australia: Preparing for the Future, was released by the government advisory research body, the Productivity Commission. It too presented the ageing society as a major concern concluding, ‘The main sources of such pressures over the next 50 years are likely to be rising obligations for publicly funded health care, aged care and retirement’ (Productivity Commission 2013: 11). The Commission also suggested that raising the eligibility age of the Age Pension to 70 should be considered: ‘… increasing the eligibility age [for the Age Pension] in line with increases in life expectancy would prima facie have some benefits’ (Productivity Commission 2013: 15). The 2015 Intergeneration Report argues that population ageing will slow down economic growth and put greater pressure on the health services (Australian Government 2015). Noteworthy, is that there is no discussion of the housing concerns of older Australians in these reports.

The presentation of the demographic shift as a major problem is certainly contestable. Mullan (2002) argues that the construction of the ageing society as a burden on developed economies is a myth and helps detract from the general crisis of advanced capitalist economies. In the Australian context, Johnstone and Kanitsaki (2009) argue ‘that the ‘demographic time-bomb’ portrayal of population ageing in Australia is misleading and incorrect’. They draw on the HSBC Future of Retirement Study (2007) of 21 000 people from 21 countries, which concludes that, contrary to the portrayal of older people by governments as a drain and a burden, ‘older people contribute billions of dollars to their nation’s economies through taxation, volunteer work and the provision of care for family members …’. The debate around the implications of an ageing society is being played out in the context of a continuing weakening of the welfare state, minimal or no economic growth in the developed economies and a dominant neoliberal discourse and policy framework that emphasises minimising government expenditure and regulation and maximising the role of the market (Harvey 2007). In this context, the housing of older Australians and the general population has been given little attention by government.2

What this book argues is that housing tenure and the related affordability, adequacy, location and security of occupancy (see Hulse and Milligan 2014 for an extended discussion of secure occupancy in rental housing) of their housing, fundamentally shape the lived experience of older people, their social in/exclusion and wellbeing, their ability to age in place and live a decent life (Colic-Peisker et al. 2015; Jones et al. 2007; Oswald et al. 2007; Windle et al. 2006). The main focus is to illustrate and explain the impact of housing tenure on the lives of older Australians primarily by using their articulations of their perspectives and concerns (see Appendix A for a detailed discussion of the methodology). Are older homeowners who are solely dependent on the single Age Pension managing financially? Are they able to maintain their homes and engage in social activity? How are older private renters who have to pay market rents faring in comparison with older homeowners and social housing tenants and how do they cope with minimal security of occupancy? What are the implications of subsidised rents and legally guaranteed security of tenure for older social housing tenants?3 These are some of the key questions considered.

The study is located within a critical gerontology approach. This approach takes cognisance of the political economy and the significance of inequality through the life course: ‘… social processes allow the accumulation of advantages over the life course for some but the accretion of disadvantages for others’ (Phillipson and Baars 2007: 78). The impacts of globalisation on older people are also highlighted in this approach. It is argued that globalisation has disrupted the stability and predictability that characterised the period up until the early 1970s, deepened inequalities and also created new possibilities for a segment of the older population. Phillipson (2007: 328) concludes that within the older population in developed economies there is now:

Social class is central to this differentiation. Upper- and middle-income households are able to accumulate savings and assets over the life course and invariably in Australia are outright homeowners by the time they retire. Households whose members have historically experienced poorly paid employment and perhaps periods of unemployment or under-employment are less likely to be homeowners by the time they permanently leave the labour force, and their savings will be limited. However, the link between housing tenure and social class in Australia is not straightforward. Noteworthy is that in Australia historically most older working-class households have been able to become outright homeowners over the life course (see Table 1.1) and the guaranteed government Age Pension does give these households a reasonable amount of disposable income, providing their housing costs are low. As this study illustrates, for people who are primarily or solely dependent on the Age Pension for their income, housing tenure is often a more significant differentiator than class. The interviews illustrated that an older person who at the end of their working life was in adequate, secure and affordable housing was far more able to live a good life than an older person who was not in this situation. The guaranteed security of occupancy and the low accommodation costs of older homeowners and social housing tenants meant that they were able to live a decent, albeit frugal, life on the Age Pension, providing they did not have any substantial and constant extraordinary expenses. In contrast, the negligible security of occupancy of older private renters, who have to use a large proportion of their Age Pension to pay for their accommodation, meant that their situation was often grim. As will be shown, many were plagued by constant anxiety due to their high accommodation costs and the ever-present possibility that they may be subject to an untenable rent increase or be asked to vacate.

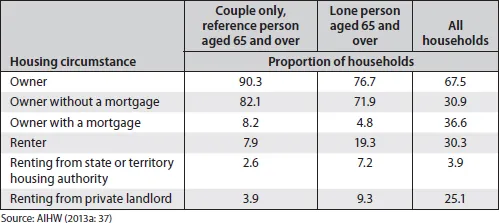

Table 1.1. Housing tenure of older Australians and all households, 2011–2012

Defining older Australians

It is evident that ageing is partially a socio-cultural construction and that within the older population there are major variations as to how people see themselves, their health status and how they experience and participate in society (Phillipson 1998; Vincent 2006). In this study, an older person is anybody who is eligible for the Age Pension. For women and men in 2015 it was 65 years. When I first began this research in 2005, it was 63 years for women and 65 years for men. From 1 July 2013, women have had to be 65 to claim the Age Pension. On 1 July 2017, the qualifying age for the Age Pension will increase from 65 years to 65 and-a-half years. The qualifying age will rise by 6 months every 2 years, reaching 67 on 1 July 2023.

Why the focus on housing tenure?

Housing has rightly been called the ‘wobbly pillar under the welfare state’ (Torgersen 1987). Whereas the key components of the welfare state – education, health and social security – are, in varying degrees, accepted as the government’s responsibility, there is little consensus as to what role governments should play in regards to the provision of housing (Kemeny 2001). Increasingly, individuals and families are expected to take responsibility for finding their accommodation in the private market (Harvey 2007). The policy shift around housing provision is bound up in a neoliberal ethos that citizens need to make their own way in the housing market (and increasingly in all other spheres) and cannot rely on government to protect them from risk (Beck 2009; Bourdieu 2003; Taylor-Gooby et al. 1999). This sentiment has been accompanied by an increasing emphasis by governments globally on home ownership, the selling off of existing social housing stock, cutting back on the provision of new social housing and growing deregulation of the private rental market (Hulse et al. 2011; Scanlon et al. 2014; Watt 2013).

The minimal involvement historically of Australian governments in the provision of housing has meant that most older Australians have always had to rely on the private market for their accommodation. Table 1.1 shows that the majority have succeeded in securing outright home ownership, although lone-person households were far less likely to be outright homeowners. In 2011–12, 82% of couple-only households, reference person 65 and over, owned their home outright, as did 72% of lone-person households aged 65 and over. An important trend is that the proportion of older private renter households, the most vulnerable group, is growing and the proportion in the social housing sector is declining. In 2011–12, about one in 11 lone-person older households were in the private rental sector (PRS), as were 4% of older couple households. In contrast, only 2.6% of older couple households and about one in 14 lone-person older households were in social housing. The changing proportions are discussed further in Chapter 2.

The housing tenure of a household does not necessarily have an impact on their everyday life and wellbeing when its members are employed. However, when they are no longer in the labour force it can be enormously significant. If they are totally dependent on government benefits for their income, their income will be fixed and almost certainly considerably less than when employed. Older homeowners who are dependent on the Age Pension will usually have far lower accommodation costs than their counterparts in the PRS and social housing, and thus more disposable income (ABS 2013a, 2015). As Yates and Bradbury (2010: 194) argue, ‘older households who miss out on home ownership are multiply disadvantaged in that they also have lower non-housing wealth, lower disposable incomes and higher housing costs in retirement’. They concluded that older homeowners had almost twice as much disposable income after accounting for housing costs.

The issue of accommodation costs is not straightforward and within these different tenures there will be substantial variations. Thus, the proportion of their income an older person living by her or himself requires for accommodation will invariably be a lot higher than that of a couple. Older homeowners who live in apartment blocks may have to pay crippling strata fees and older private renters who reside in metropolitan areas will generally have higher accommodation costs than their counterparts in regional locations. Accommodation costs and their myriad impacts for people dependent on the Age Pension are discussed in detail in Chapters 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7.

The other key issue in relation to housing tenure is security of occupancy. Older homeowners who own their homes outright and tenants in social housing usually have guaranteed security of occupancy. There is little or no possibility that they will lose access to their accommodation. Older private renters are in a different position. The limited regulation of the PRS in Australia means that almost all private renters have minimal legal security of tenure once their written agreement ends after 6 or 12 months (Hulse et al. 2012).4 The impacts of having or not having security of occupancy are profound and is a central theme of the book. The regulation of the PRS is discussed in more detail in Chapters 2 and 8.

The scarcity of affordable and secure private rental accommodation, combined with the shortage and stigmatisation of social housing, makes the pursuit of home ownership a sensible option in Australia. Kemeny (2001: 67) has effectively summarised this situation:

In those European countries with high levels of affordable and secure rental accommodation and with adequate Age Pension systems, home ownership, not surprisingly, is much lower than it is in Australia (Hulse et al. 2011; O’Sullivan and De Decker 2007). Home ownership in these contexts is not viewed as a necessary requirement for secure and affordable living in retirement (Castles 1998; Doling and Horsewood 2011). Probably the most outstanding example is Switzerland. In 2005, despite it being one of the world’s wealthiest countries, ~65% of households lived in private rented accommodation (Lawson 2009: 47). In 2008, in Germany, ~60% of households were renters and in the Netherlands and Austria this proportion was ~40% (Hulse et al. 2011; O’Sullivan and De Decker 2007).

The high level of home ownership in Australia has important implications for the Age Pension payment rate. Kemeny (2001, 2005) argues that in countries with high levels of outright homeownership, there is less pressure on governments to introduce high Age Pensions because of the low housing costs of outright homeowners.

This study examines Kemeny’s argument. Are older homeowners and social housing tenants able to live a decent life if they are solely or mainly dependent on the Age Pension and what are the implications for older private renters of being subject to market rents? These questions are examined in depth in Chapter 4.

Why the focus particularly on older Australians and housing?

Housing tenure is certainly important for all age groups in Australia. However, in the case of housing, older Australians do have particular issues and challenges. Besides the increasing size of this cohort absolutely and as a proportion of the population, there are several other distinctive features. The greater likelihood of ill health, disability, widowhood and living alone are all important features, as is the large-scale dependence on the Age Pension. Finally, the relatively extensive amount of time older people spend in their home means that their housing situation is usually a vital contributor to their wellbeing. These aspects are discussed in turn.

Older people, housing and health

There is consensus that poor housing and/or stress around one’s housing circumstances is associated with reduced health ...