![]()

1

Berlin

The early years

Many of the men who would become Michael Josselson’s CIA colleagues came of age in the infancy of the “American century,” their patriotism reinforced by family traditions of government service, boarding schools, and overlapping social circles.1 Josselson was instead born in 1908 in Tartu, Estonia. “The simple mention of being born in Estonia,” Josselson reflected, “inevitably produces an embarrassed ‘Oh, yes?’ or, what is infinitely worse, the quasi-knowledgeable ‘You mean you are from Riga?’”2 He was nine when his family fled the Bolshevik Revolution, which reached Estonia in 1917. His father, a Jewish lumber merchant, moved the family to Berlin; they arrived the year before Germany’s disastrous defeat in the First World War.3

Josselson came of age in the short-lived golden days of the Weimar Republic, a country plagued by hyperinflation, crippled by the Versailles Treaty, and battered by political crises. Yet it briefly supplanted Paris as a beacon of culture. Historian Peter Gay wrote:

When we think of Weimar we think of modernity in art, literature, and thought; we think of the rebellion of sons against fathers, Dadaists against art, Berliners against beefy philistinism, libertines against old-fashioned moralists; we think of The Threepenny Opera, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the Bauhaus, Marlene Dietrich.4

For Josselson, it gave him the greatest cultural education the twentieth century had to offer, and he attended hundreds of performances. Artur Nikisch, whom Josselson deemed “the dean and forerunner of all the great German conductors,” was at the Berlin Philharmonic. Violinist Yehudi Menuhin soloed there as a boy. In the Grosse Schaulspielhaus, Max Reinhardt put on productions of Julius Caesar.5 Berlin’s “quite large” Russian expatriate colony of “perhaps fifty thousand” was, Josselson felt, a “world in itself,” where intellectuals mingled with “doctors, lawyers, businessmen.” He knew Vladimir Nabokov as a “very good tennis player” from the courts on the Lietzenburger Strasse and devoured his short stories.6 “Mike’s notions of culture and the importance of culture,” Hunt reflected, “came from Germany.”7

But, by the late twenties, the Nazi Party’s inroads among universities made Germany an uncomfortable place for a Jewish émigré. In 1928, three semesters into a history degree at the University of Berlin and running out of money, Josselson accepted a job with Gimbels, the American department store.8 The offer was not just well-timed luck. Josselson had wangled a student internship at Gimbels’ Berlin office buying toys and luxury goods for American stores.9 Taken on his first trip to meet a seller, a Czech handbag manufacturer, twenty-year-old Josselson made a deal for several thousand handbags at a price far below the one his boss had futilely demanded for hours. His career as a buyer seemed assured.10

The job had a certain glamor. Gimbels was then the premier department store in America and the biggest buyer in Europe, and department stores were also auction houses, galleries, and sponsors of art exhibitions. Gimbels sponsored a tour of Cubists around the country, displayed Rembrandts in its old masters gallery, and put on two concerts daily. Along with its competitors, Gimbels was “more influential than all the nation’s museums combined” in exposing Americans to fine art, according to the president of New York’s Metropolitan Museum.11

By 1935, Josselson, then aged twenty-seven, was in charge of all Gimbels purchases from Czechoslovakia. Two years later, he was in Paris as the head of all European purchases, choosing everything from couture to sundries. He joined the French Racing Association and the Chamber of Commerce. His travels took him to Berlin, Prague, and even the Soviet Union. He began dating Colette Joubert, a blonde Frenchwoman who worked at Saks.

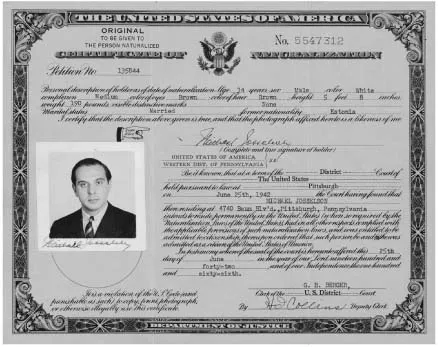

Then war began, and European markets collapsed. Josselson had safe passage to America, but Colette’s visa took nerve-wracking months. They arrived in New York just before the fall of France, married in Cuba, and moved to Gimbels’ Pittsburgh headquarters.12 Josselson became a citizen in 1942 and an Army conscript in 1943.13 He would never live in America again.

In the Army, Josselson advanced quickly. His fluency in Russian, French, and German as well as English drew the attention of General Robert McClure’s Psychological Warfare Division, created in 1944 as the nerve center for all psychological activities against the Axis powers.14 He became an interrogator; the job “amounted to our roaming around and constituting the eyes and ears of the intelligence section of the PWD up and down the Front, or rather prisoner of war cages,” his colleague Leo Fialkoff remembered.15

Four years after fleeing the continent, Josselson was in newly liberated France, spending twelve-hour days interrogating prisoners of war. Occasionally, figures from his old life beckoned him back. In the champagne houses at Reims, the managers abandoned prominent American clients to embrace him. He attended the Théâtre de la Mode, the legendary Paris couture show staged with puppets due to fabric shortages.16 But, by now, Josselson saw the war as a welcome escape from his old life as a buyer – “They were only interested in money, nothing else.”17 His marriage was over.18 His unit was bound for Berlin; as one of the only Russian speakers in the unit, he was the obvious choice for the position of liaison to the quadripartite government.19 In July 1945, Josselson thus was among the first Americans to arrive in the home he had left two decades before.20

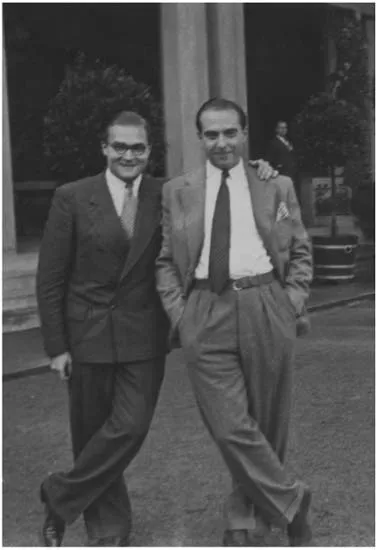

Figure 1.1 Michael Josselson (right) with his brother Peter, Paris, 1938 (reproduced with permission of Jennifer Josselson Vorbach).

Figure 1.2 Josselson, as shown in his naturalization form, became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1942 (reproduced with permission of the Ransom Center).

Nothing in Berlin seemed to have escaped the war. The city center was a graveyard of shelled tanks. The Reichstag had lain abandoned since the 1933 fire, its columns mottled by burn marks. The Tiergarten was a field of stubs, its stately trees long since hacked into firewood.21 Corpses clogged the canals; summer heat made the smell unbearable.22 Prewar Berlin’s busiest intersection had reverted to nature; wild rabbits darted through a dark mass of overgrown weeds and nettles.23

The Red Army had won the Battle of Berlin with block-by-block fighting. For the next two months it was the sole victor on the ground, and it descended with a vengeance, raping tens of thousands of women, from preadolescent girls to great-grandmothers.24 Berlin had lost one-third of its population, and, of the survivors, half a million women were reduced to prostitution.25 Food shortages worsened; Berliners subsisted on under 1,000 calories a day.26

Yet signs of recovery emerged. Less than three weeks after the surrender, the Philharmonic was playing Mendelssohn’s joyful Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, banned under the Nazis.27 Theaters, opera houses, and symphonies performed anew. Cabarets came back by the dozen.28 A thriving black market sprung up in Alexanderplatz, fueled by Russian soldiers flush with newly minted occupation marks. (The American government had made the expensive mistake of turning over its own currency plates so Stalin could pay his soldiers years of back pay.) In Russia, a watch could be exchanged for an entire cow; in Berlin, Red Army soldiers wore half a dozen per arm, and the Mickey Mouse watch became Berlin’s most prized commodity.29

In the two months before Josselson arrived with the first wave of American occupiers, the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD) set its own plans in motion. Those plans became the province of Colonel Sergei Tulpanov, head of SMAD’s Information Department.30 Born in 1901 to a family of educated peasants, Tulpanov was forty-four when he came to Berlin, immense, egg-bald, and a protégé of Andrei Zhdanov, the Cominform’s future head. Tulpanov arrived fluent in German and with a singular feel for the situation on the ground. In his view, the creation of a divided Germany was inevitable; the object was to consolidate Soviet control as rapidly as possible.

At a time when other Soviet commanders favored slowly building a sphere of influence without risking access to West German industrial centers, Tulpanov was an outlier. His rivals lobbied their superiors in Moscow for his removal. That his parents were convicted spies made him a perennial candidate for investigation. Time was of the essence, because he could never be ...