![]()

1

The Greeks, the Romans and the Garamantes

Libya is rich in the ruins of ancient Roman and Greek cities. In the south there are signs of a lost African civilisation, which the Romans called the Garamantes.

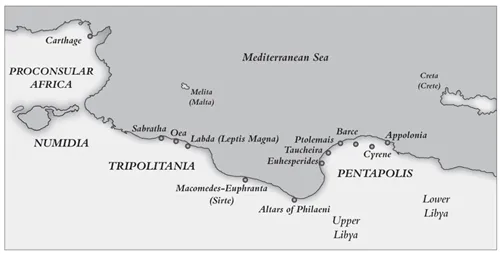

Even when these civilisations were at the height of their powers they were mostly separated by geographical barriers. The west was Roman, the east was Greek and the south, African. The three Libyan provinces of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and the Fezzan, which arose amongst the remains of these civilisations, were influenced by their ancient predecessors. The Gaddafi regime abolished the old provincial names, calling Tripolitania West Libya, Cyrenaica East Libya and the Fezzan South Libya. However, the provinces live on in spirit to make it difficult to unify modern Libya.

The civil war that broke out in Libya on 17 February 2011 reflected deep differences between the old provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. Apart from the physical separation by the inhospitable desert region of the Sirtica, the history of the two regions has been very different. Greece and Egypt have long influenced Cyrenaicans and Carthage and Rome Tripolitanians. The remote desert province of the Fezzan has forever been involved with sub-Saharan Africa by reasons of human kinship and the trans-Saharan trade in slaves, gold and wild animals. The people of the three provinces are therefore separated by differences that have persisted for thousands of years.

The border between Tripolitania and Cyrenaica meets the coast at a legendary spot called the Altars of the Philaeni. It was said that the Phoenician founders of Tripoli were so jealous of their trade that they excluded the Greeks of Libya Pentapolis, in what was known until recently as Cyrenaica. The place that marked the border between them became a bone of contention.

Legend has it that the Phoenicians and the Greeks, after a number of skirmishes, agreed to establish the frontier between their two territories by means of a foot race. Runners were to set off towards each other from Carthage in the west and Cyrene in the east. Where they met was to mark the frontier.

The Phoenician team, the Philaeni brothers, reached a point in the desert at the southern extremity of the Gulf of Sirte before they met the Greeks. The Greeks were angry because they expected their team to get further, and so they accused the Philaeni brothers of cheating. The Phoenicians denied it, so both parties agreed to settle the dispute by burying the Philaeni brothers alive to mark the frontier. Two mounds were said to have been built over the graves, on which the Altars of the Philaeni were erected. This is an unlikely story, but one that reflects the intensity of the original dispute.

In the twentieth century, Mussolini built a triumphal arch on the border as a monument to his African conquests. This pompous edifice looked similar to the arch at the top of Park Lane in London. British Second World War soldiers, whose dry sense of humour was legendary, called it Marble Arch, so it was known thus throughout the 8th Army and the name stuck.1 My wife and I drove past the Marble Arch on our way from Tripoli to Benghazi. It had a large bronze human figure somehow appended to the side. One of its big toes had been cut off. Sometime later I saw a grotesque bronze object on the desk of an Englishman in Benghazi. It was the missing toe, which he had cut off and was using as an ashtray.

For more than four centuries, the two provinces were joined under Roman rule. There was a common language, a cohesive government and a common legal system. Ruins of the great cities still grace the Libyan shores of the Mediterranean and have within them common and unifying features – pubic baths, stadia, theatres, art and architecture – found throughout the Roman Empire. Even so, the ruins of Tripolitania are clearly Punic in character, whilst those of Cyrenaica are unmistakably Greek.

The Punic and Greek cities of Libya. Sabratha, Oea and Leptis Magna became Roman cities after the Punic wars. The Greek cities of Libya Pentapolis were eventually taken over by Rome. (The legendary Altars of Philaeni were erected to mark the boundary between the Punic east and the Greek west.)

The archaeological and historical evidence tells us that Christianity spread across the two provinces in the second century AD. It may have been spread by the Jewish communities and found ready converts amongst the slaves and the indigenous Berbers. However, the churches of Tripolitania looked to the Bishop of Rome for leadership, whilst those of Cyrenaica were in the diocese of the Coptic Patriarch of Alexandria. The differences in religious observance created animosities between people during hard economic times and often, as they do today, led to warfare.

My own interest in the early history of Libya grew out of familiarity with the ancient ruins and contact with anthropologists and archaeologists working on such diverse subjects as the possible Jewish origin of the cave dwellers in the Gebel Nefusa and the export trade from the ancient Greek port of Tokra (Taucheira). Sometimes I was asked to help them during the ‘digging’ seasons, though in practical ways, such as solving those little local difficulties with authorities that were endemic in Libya and probably still are.

My belated apologies are extended to the charming and forgiving team which, in the 1960s, went to Cyrene to explore the huge stone-built pipelines connecting that city with its hinterland. They came to me to hire or borrow a Land Rover, which I obtained for them from my friend Mohammed al Abbar. It was not a good vehicle on which to depend in the remote and slightly hazardous region in which they worked, but I was obligated to al Abbar and their troubles with it were a by-product thereof. Interestingly, this team concluded that the pipelines were used to transport olive oil for the city from the olive groves; though how this might have worked was always a mystery to me.

This story makes two points. The first is that the ancient cites must have been supported by large and efficient agricultural enterprises, now lost or destroyed. The second is that the ‘currency of obligations’ is very powerful in modern Libya and is a factor that needs to be taken into account by Westerners.

It is best, perhaps, to start with the three ancient Tripolitanian cities before looking briefly at the classical Greek civilisation in Cyrenaica. There is method in this. It will help to understand the differences between the provinces of modern Libya. It will also lead us into the important work being done by archaeologists on the remains of lost civilisations. We will surely hear more of this work when it is safe for archaeologists to return to Libya after the civil war.

The Phoenicians and the Garamantes

A question that modern visitors to the three cities, Sabratha, Oea (Tripoli) and Leptis Magna, often ask is why they were first established so close together on the Mediterranean shore of Tripolitania. The visitors are puzzled because the three of them, existing together in such close proximity, would have outstripped the natural resources of the coast or its immediate hinterland.

The question forces us to venture into the insecure realms of conjecture and hypothesis. We know that the three cites originated as Phoenician trading posts, which were taken over by the Carthaginians, whose great city, Carthage, came to dominate the coast. The Phoenicians and the Carthaginians were traders first and last. They guarded their trade secrets with paranoid zeal, leaving few clues for archaeologists to unravel. To add to our problems, the city of Carthage was totally destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC and with it all the records that might have helped us as historians.

Since we believe that trade outweighed politics for the Carthaginians, we might suggest that the three cities were established primarily as trading posts. We might go further and argue that Sabratha, Oea and Leptis Magna were founded by three separate trading houses, all engaged in the same trade.

Business must have been very good indeed to support three such emporia. The maritime carrying trade, that is the shipping and the trading of goods around the Mediterranean, would not have been sufficient. We must look elsewhere for a reason.

It may lie to the south, in what was once the Fezzan. In ancient times it was the territory of the Garamantes, a long-lost people to whom some, though significantly not all, attribute the rock paintings that still remain in good condition to the wonder and puzzlement of those rare and lucky people who ventured into the arid wastes of South Libya.

One other recurrent traveller’s tale about the Fezzan was that its early inhabitants used chariots. Visitors to Tripoli museum today will find there a replica of a chariot believed to have been used by the enigmatic Garamantes. They were said by Strabo to breed 100,000 foals per year. This suggests that the terrain was suitable for their use. Horses, which need frequent access to water and plenty of fodder, are not suitable for long-distance travel in desert conditions. The implication is that access to water and fodder was widely available when these chariots were in use and the intensive horse-breeding programme was active.

Perhaps one of the most surprising references to the ancient civilisation in the Fezzan is this, found in a letter written in January 1789 by Miss Tully, the sister of the British consul to the Karamanli court of Tripoli. In it she describes the Prince of Fezzan, and something of his kingdom, thus:

The Prince of Fezzan’s turban, instead of being large and of white muslin like those of Tripoli, was composed of a black and gold shawl, wound tightly several times round the head, and a long and curiously wrought shawl hung low over the left shoulder. The baracan was white and perfectly transparent; and his arms were handsome, with a profusion of gold and silver chains hanging from them.

He told us his country is the most fertile and beautiful in the world, having himself seen no part of the globe but Africa; and Fezzan esteemed amongst the richest of its kingdoms.

In the Fezzan there are still vestiges of magnificent buildings, and a number of curiously vaulted caves of immense size, supposed to have been Roman granaries. But it requires a more enlightened mind than that of the Moor and the Arab to discover their origin.2

Miss Tully, whose work is discussed elsewhere in this short history, was describing a visit to Tripoli by the Prince of Fezzan during the Karamanli regency. That she was observant enough to note the profusion of gold which adorned the prince, and that the Fezzan still boasted a number of mysterious and notable ruins, is not surprising. She was, as we shall see, an excellent observer and most thorough in her research. The African source of gold, so ostentatiously adorning Miss Tully’s Fezzanese guests, was to become one of the great mysteries of the late Georgian age in Britain.

In more peaceful times, before the present civil war in Libya, archaeologists were engaged in studying the numerous and intriguing cave paintings and also attempting to bring the Garamantes into better focus. Thanks to David Mattingly and his team from the University of Leicester and Andrew Wilson of the University of Oxford, we now know that the Garamantes were able to tap into the vast aquifer of water deep under the Saharan desert; the same water that has been exploited in modern times by Gaddafi in his ‘Great Man Made River’ scheme, of which more soon.

The archaeologists have concluded that the Garamantes constructed almost 1,000 miles of underground tunnels and shafts, known locally as foggara, to get at the artesian water. These are the vaulted caves mentioned by Miss Tully. We may also conclude that they would have used many slaves to construct the tunnels. Others have noted that they silted-up frequently and needed constant cleaning. It is clear that the abundant supply of water was used to support an extensive and sophisticated agriculture and a large population.

The archaeologists believe that by AD 105 the Garamantian state covered 70,000 square miles of the Fezzan and that there were eight towns and many settlements. (I understand that David Mattingly has concluded that the water ran out in the end, causing the civilisation to wither away; a salutary lesson for us all. Others, Robert Graves amongst them, argue that the Garamantians merely left for new lands elsewhere.)3

Studies of the Garamantian capital, now the town called Germa, tell us that it was guarded by six towers and that it may have had a market square used for trading horses, which were sold to the Romans. It also served as a transit stop for caravans, probably from the south, on their way along what is now known as the Garamantes Road, which terminated near Tripoli.

More than 50,000 pyramidal tombs have been discovered in the Fezzan, including one thought to have been for royalty at Ahramat al-Hattia. There is a museum in Germa in which are a number of artefacts, including some well-preserved cave art in which giraffes and a large ox are depicted. These animals, which we now associate with East and South Africa, were clearly able to survive in the Fezzan when these paintings were made.

Trade with the Garamantes was not just the possible, but the principal reason for founding the three large emporia so close together on the coast of the Lesser Sirte.

The Romans

The Punic wars are familiar enough to need only a few words here. They ended when the Romans razed Carthage to t...