Chapter 1

The Cold War

Beginnings

The Cold War of the two postwar superpowers was not an episode like other wars of modern times. The term ‘cold war’ was invented to describe a state of affairs. The principal ingredient in this state of affairs was the mutual hostility and fears of the protagonists. These emotions were rooted in their several historical and political differences and were powerfully stimulated by myths which at times turned hostility into hatred. The Cold War dominated world affairs for a generation and more.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt had believed, or perhaps only hoped, that he could persuade Joseph Stalin not to create a separate Soviet sphere of influence over eastern Europe but to co-operate instead with the United States in creating a global economic order based on free trade and beneficial to all involved, not least the USSR. Wartime Lend-Lease to the USSR had been a first step; the postwar Marshall Plan was to be a somewhat forlorn last hope, for even after Roosevelt’s death in April 1945 there were some in Washington who preferred a policy of resuscitating western Europe without military confrontation with the USSR. But to most Americans the USSR seemed dedicated to the conquest of Europe and the world for itself and for communism and was capable of achieving, or at least initiating, this destructive and evil course by armed force abetted by subversion. On this view the necessary riposte by the United States was military confrontation in alliance with Europeans and others and on the assumption that Soviet hostility was ineradicable. Seen from Moscow, the western world was inspired by capitalist values which demanded the destruction of the USSR and the extirpation of communism by any means available, but above all by force or the threat of irresistible force. Both these appreciations were absurd. When the Second World War ended the USSR was incapable of further military exertion, while the communist parties beyond its immediate sphere were unable to achieve anything of significance. The western powers, while profoundly mistrustful of the USSR and hostile to its system and beliefs, had no intention of attacking it and were not even prepared to disturb the dominance of central and eastern Europe secured by its armies in the last years of the war. Each side armed itself to win a war which it expected the other to begin but for which it had no stomach.

The focus of the Cold War was Germany, where confrontation over Berlin in 1948–49 came close to armed conflict but ended in victory for the western side without a military engagement. This controlled trial of strength stabilized Europe, which became the world’s most stable area for several decades, but hostilities were almost simultaneously carried into Asia, beginning with the triumph of communism in China and war in Korea. These events led in turn to an acceleration of the independence and rearmament of West Germany within a new Euro-American alliance and to a succession of conflicts in Asia, of which the Vietnam War was the most devastating. At no point did the protagonists directly engage each other but both sought to extend their influence and win territorial advantage in adjacent parts of the world, notably the Middle East and – after its decolonization – Africa. None of these excursions was decisive and for nearly half a century the chief outward expression of the Cold War was not advances or retreats but the accumulation and refinement of the means by which the two sides tried to intimidate each other: that is to say, their arms race. The slackening of the Cold War resulted from the combined effect of the huge cost of these armaments and the gradual waning of the myths which underlay it.

In the summer of 1945 it was known both in Washington and Moscow that Japan was ready to acknowledge defeat and abandon the war which it had begun by the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. In July the Americans experimentally exploded the first nuclear weapon in the history of mankind and in August they dropped two bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan surrendered forthwith and this clinching of the imminent American victory deprived the Russians of all but a token share in the postwar settlement in the Far East.

In the European theatre conflict remained for a short time veiled. The organs and habits of wartime collaboration were to be adapted to the problems of peace, not discarded. The Russian spring offensive of 1944 had set the USSR on the way to military dominance and political authority in Europe unequalled since Alexander I had ridden into Paris in 1814 with plans for a concert of victors which would order the affairs of Europe and keep them ordered. The nature of mid-twentieth-century great power control was a matter for debate – how far the powers were collectively to order the whole world, how far each was to dominate a sector. The Russians and the British, with the reluctant assent of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (and the dissent of his secretary of state, Cordell Hull), discussed the practical aspects of an immediate division of responsibilities, and in October 1944, at a conference in Moscow which the president was unable to attend owing to the American election campaign, these dispositions were expressed in numerical terms. About western Europe no questions arose because western control was uncontested. Poland was not included because, in parts effectively, in parts imminently, it was under Stalin’s military control. Elsewhere the realities were expressed by Winston Churchill as percentages. The Russian degree of influence in Romania was described as 90 per cent, in Bulgaria and Hungary as 80, in Yugoslavia 50, in Greece 10. In practice these figures, although expressed as a bargain, described a situation: 90 and 10 were polite ways of saying 100 and 0, and the diagnosis in the two extreme cases of Romania and Greece was confirmed when the British took control in Greece without Russian protest and the USSR installed a pro-communist regime in Romania with only perfunctory American or British protest. Bulgaria and Hungary went the same way as Romania for military reasons. Yugoslavia appeared to fall within the Russian sphere but soon fell out of it. Europe became divided into two segments appertaining to the two principal victors, the United States and the USSR. These two powers continued for a while to talk in terms of alliance, and they were specifically pledged to collaborate in the governance of the German and Austrian territories which they and their allies had conquered.

The position of the USSR in these years was one of great weakness. For the USSR the war had been a huge economic disaster accompanied by loss of life so grievous that its full extent was not disclosed. The Russian state was a land power which had expanded generation by generation within a zone which evoked a persistent German threat. In the Soviet phase of history Russian external politics were further characterized by a diplomacy which led to isolation and so, in 1941, to the threshold of military defeat. The USSR had been saved by its extraordinary geographical and spiritual resources and by the concurrent war in the west in which the Germans were already engaged before they attacked the USSR and which became graver for them when, shortly afterwards, Hitler gratuitously declared war on the United States of America. For Stalin, however, the anti-fascist alliance of 1941–45 can hardly have appeared to be more than a marriage of convenience and limited span; nor did it look any different when seen from the western end, at any rate by governments, if not in the popular view. With the war over, the purpose of the alliance had been achieved, and there was little in the mentalities and traditions of the allies to encourage the idea that it might be converted into an entente: on the contrary, the diplomatic history of all parties up to 1941 and their respective attitudes to international political, social and economic problems suggest exactly the reverse.

The elimination, permanent or temporary, of the German threat coincided with the explosion of the first American nuclear bombs. For the first time in the history of the world one state had become more powerful than all other states put together. The USSR, no less than the most trivial state, was at the mercy of the Americans should they be willing to do to Moscow and Leningrad what they had done to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There were reasons for supposing that they were not so willing, but no government in the Kremlin could responsibly proceed upon this assumption. Stalin’s only prudent course in this bitterly disappointing situation was to combine the maximum strengthening of the USSR with a nice assessment of the safe level of provocation of the United States, and to subordinate everything, including postwar reconstruction, to catching up with the Americans in military technology. He possessed a large army, he had occupied large areas of eastern and central Europe, and he had natural allies and servants in communists in various parts of the world.

At home his tasks were immense: they included the safeguarding of the USSR against a repetition of the catastrophe of 1941–45, and the resurrection of the USSR from the catastrophe which had cost 25 million or perhaps even 40 million lives, the destruction or displacement of a large part of its industry and the distortion of its industrial pattern to the detriment of all except war production, and the devastation and depopulation of its cultivated land so that food production was almost halved. To a man with Stalin’s past and temperament the tasks of restitution included the reassertion of party rule and communist orthodoxy and the reduction therefore of the prominence of the army and other national institutions and the reshackling of all modes of thinking outside the prescribed doctrinal run. In matters of national security, in economic affairs and in the life of the spirit the outlook was grim. At home artists and intellectuals were regimented, victorious marshals were slighted and the officer class persistently if quietly purged, while the first postwar five-year plan prescribed strenuous tasks for heavy industry and offered little comfort to a war-weary populace.

Externally, Stalin made it clear that the protective acquisitions of were not for disgorging (the three Baltic states, the eastern half of Poland which the Russians called Western Ukraine and Western Byelorussia, Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, and the territory exacted from Finland after the winter war); elsewhere in eastern and central Europe all states must have governments well disposed to the USSR, a vague formula which seemed to mean governments which could be relied upon never again to give facilities to a German aggressor and which came, after 1947 or thereabouts, to mean governments reliably hostile to the United States in the Cold War. Such governments must be installed and maintained by whatever means might be necessary. During the wartime conferences between Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill parts of the USSR were still occupied by German forces, and during the war and its psychological aftermath (a period of indefinable duration) Stalin was no doubt obsessed with his German problem. The Cold War first substituted the Americans for the Germans as the main enemy but then, after the rearmament of Western Germany, combined the two threats as a new American–German one. These developments, to which Stalin himself contributed by his actions in eastern and central Europe, may nevertheless have been a disappointment to him if, as seems possible, he had entertained at one time a very different prospect of Russo-American relations.

To Stalin during the war the Americans were personified by Franklin D. Roosevelt, who made no secret of his desire to get on well with the USSR or of his distrust of British and other western imperialisms. Moreover, Roosevelt wanted a Russian alliance against Japan and did not seem at all likely to do the one thing which Stalin would have feared; namely, to keep troops permanently in Europe and make the United States a European power. On the contrary, Roosevelt was not much interested in postwar Europe and showed, for example, little of Churchill’s concern about what was going to happen in Poland and Greece. Whereas Russo-British relations came near to breaking-point over Poland, Russo-American relations did not; and Stalin, whether out of genuine lack of interest or calculated diplomacy, avoided serious disagreement with Roosevelt over problems of world organization as the representation of Soviet republics in the UN) in which Roosevelt was seriously interested. On the basis that the United States would be remote from Europe and in some degree friendly towards the USSR, Stalin was prepared to moderate his support for European communists in order not to alarm the United States. He did not foresee that by abandoning Greece to Britain he was preparing the way for the transfer of Greece to the United States within three years. His failure to help the Greek communists may have been principally a result of a calculation that they were not worth helping, but he may also have reflected that helping them would alarm and irritate Americans in Roosevelt’s entourage. He was continuing a line of policy applied in Yugoslavia during the war when he restrained the Yugoslav communists’ desire to plan and prosecute their social revolution while the war was still in progress, and urged them to co-operate with other parties, even monarchists. Again he persuaded the Italian communists to be less anti-monarchical than the non-communist Action Party; it was the communist leader Palmiro Togliatti who proposed, after the fall of Mussolini, that the future of the Italian monarchy should remain in abeyance until the war was finished. By that time, however, Roosevelt was dead and whatever Stalin’s policies towards the United States may have been, they could no longer be based on his relations with Roosevelt and his estimate of Roosevelt’s intentions. Even if Roosevelt had survived, his policies might have been radically altered – as were those of Harry S. Truman, who succeeded Roosevelt in April 1945 – by by ccessful explosion of two nuclear bombs and by the evolution of Stalin’s policies in Europe.

For Stalin, confronted in August 1945 with the evidence from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the outstanding fact was that the USSR possessed no strategic air force which could deliver a direct attack on the United States. The best that Stalin could do was to pose a threat to western Europe which might deter the Americans from attacking the USSR. The Russian armies were not demobilized or withdrawn from the areas which they had occupied in the last campaigns of the war and which included the capital cities of Budapest, Prague, Vienna and Berlin. Thus Stalin created a glacis in advance of his vulnerable heartlands and at the same time scared the exhausted and tremulous Europeans and their American protectors into asking themselves whether the Russian advance had really been halted by the German surrender or might be resumed until Paris and Milan, Brest and Bordeaux were added to the Russian bag. But by keeping a huge army in being and reducing most of central and eastern Europe to vassalage while Russian money and brains were producing the Russian bomb, Stalin accentuated the American hostility which he had cause to fear.

Nuclear parity was an inescapable objective for the Kremlin, but there was in theory an alternative, which some Americans tried to bring within the scope of practical politics. This was to sublimate or internationalize atomic energy and so remove it from inter-state politics. One of the first actions of the United Nations was to create in 1946

1.1 The Cold War division of Europe

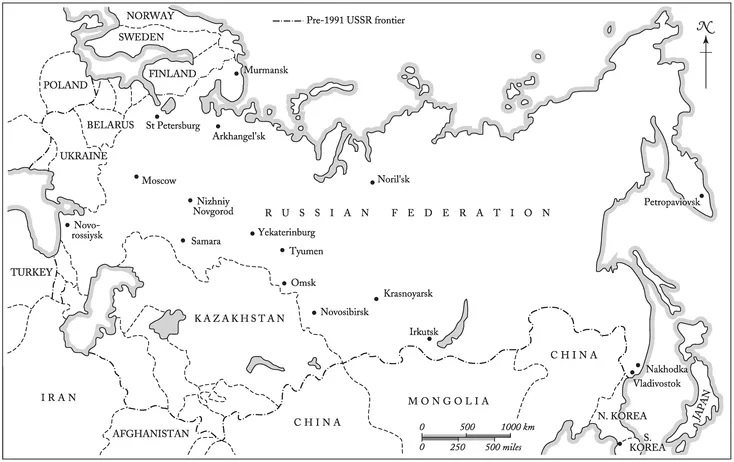

1.2 The Russian Federation and its neighbours

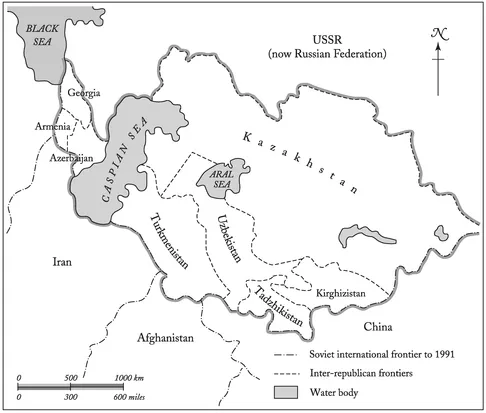

1.3 The five central Asian states and the Caucasus

an Atomic Energy Commission. At the first meeting of this commission Bernard M. Baruch presented on behalf of the United States a plan for an international Atomic Development Authority which would have exclusive control and ownership in all potential war-making nuclear activities. The Russians presented a different plan. The two plans were irreconcilable and in 1948 the Atomic Energy Commission decided to adjourn indefinitely. The Russian rejection of the Baruch Plan was an additional factor in persuading Truman that the USSR was no longer an ally but a dangerous adversary.

American policy-makers had more freedom of choice than their Russian counterparts. The nuclear bomb was a weapon which had been used to bring the war with Japan to an end and also a political weapon with which to shackle Russian power. The war left the United States a major power in Europe with considerable military forces in Europe and nuclear weapons in the background. Endowed with mighty technical superiority, the Americans might strike or threaten, or wait and see. To strike – to start a preventive war – was in practice impossible because they were unable to summon up the will to do so. A preventive war is a war undertaken to remove a threat by a people which feels threatened, and the Americans did not feel threatened by Russian weaponry: a preventive war was an abstract intellectual concept. (For the Russians it was substantive but also suicidal.) The Americans therefore pursued policies which combined threats with waiting to see.

All weapons have political implications and the biggest weapons have the biggest implications. A weapon which is too frightful to use – or turns out to be, in military terms, useless except in the most exceptional circumstances – has the most implications, since its possessors will want to put it to political use in order to compensate for the anomalous limitations on its military usefulness. Truman’s position was automatically different from Roosevelt’s as soon as Hiroshima had been destroyed. The question was not whether he was to make political use of the new weapon, but to what political end he should use it. The context in which this question first arose was not Asian but European, for it was in Europe that the principal political issues lay. The United States disliked the idea of spheres of influence, and in particular the prospect of exclusive Russian control over half Europe as the Russians broke pledges to install democratic governments in countries liberated from German rule. In addition the climate of opinion was changing. Truman was a very different man from Roosevelt and conscious of the differences: an American of some eminence but in no sense a world figure, a man respected for the qualities which go with directness rather than subtlety, a man in whom political courage would have to take the place of political sophistication, a man typically American in his attachment to a few basic principles where Roosevelt had generally preferred the modes of thought of the pragmatist. Truman, in the last resort, played politics by precept and not by ear, and where Roosevelt had been concerned with the problem of relations between two great powers, Truman was more influenced by the conflict between communism and an even vaguer entity called anti-communism. Again, so far as these generalizations are pardonable, Truman was the more representative American of the late 1940s and more inclined to regard the meeting of Americans and Russians in the middle of Europe as a confrontation of systems and civilizations rather than of states. Reports of indiscipline and barbarities by Russian troops, often described as Asian or mongoloid, increased this propensity.

The United States had some cause to hope that the implications of Hiroshima for Europe were not lost on the Russians. Elections in Hungary in 1945 gave the communists only a minor share in the government of the capital and the state. Elections in Bulgaria were postponed on American insistence and against Russian wishes. In Romania the United States aligned itself with the anti-communists and the king against the prime minister, Petru Groza, whom (although not a communist) the Russians had installed when they entered the country in 1944. But the crucial testing ground was Poland, where coalition government, under a socialist prime minister, was maintained until 1947 but gradually transformed in that and the following year – the years which saw the extinction of any hope of preventing the partition of Europe into spheres of influence and the formalization of the Cold War.

American policy veered away from the attempt to maximize American influence throughout Europe in favour of giving the USSR to understand that further territorial advances in Europe were forbidden. This prohibition was to be enforced by a series of open political arrangements, backed by military dispositions. The overwhelming power of the United States would be used obstructively but not destructively. In so far as the USSR presented a material menace, it would be contained by physical barriers; in so far as it presented an ideological menace, it would be countered by democratic example, money and the seeds of decay which westerners discerned in the communist system (as Marxists did in capitalism). American policy was also constructive and reconstructive. The UN Relief and Reconstruction Agency (UNRRA) was financed mainly by American money; its help was enormous, especially to the USSR and Yugoslavia. In March 1947 the United States took over Britain’s traditional and now too costly role of keeping the Russians out of the eastern Mediterranean: Truman took Greece and Turkey under the American wing and promised material aid to states threatened by communism. Three months later the United States inaugurated the Marshall Plan to avert an economic collapse of Europe which could, it was feared, leave the whole continent helplessly exposed to Russian power and communist lures. The offer of American economic aid was made to the whole of Europe, including the USSR, but Moscow refused for itself and for its satellites. For a second time – the Baruch Plan being the first – the Russians rejected a generous overture from Washington rather than accept collaboration which would have enabled Americans and others to move around in the USSR and observe its true plight. Separate development of western and eastern Europe was affirmed. Europe was still a battlefield – not, as Europeans mostly saw it – a zone where yet another war had just ended. The coup which substituted communist for coalition rule in Prague the next year sharpened the image of the battlefield, for although there was no fighting except locally and sporadically, everybody concurred in describing the situation as a war. Then, in Germany the struggle for the only important piece of Europe in dispute between the two camps produced a challenge which seemed bound to lead to shooting.

The division of Germany

At the end of the Second World War the United States, the USSR and Britain were in apparent agreement on two propositions about Germany, both of which they fa...