![]()

Chapter

1

Why Plan?

Why even bother with planning? Isn’t life complicated enough just trying to solve the problems that present themselves on a day-to-day basis without gazing into the future to find new ones? Doesn’t the city council have a crowded enough calendar just trying to make decisions on things that matter right now without focusing on future problems that may or may not happen?

For both citizen and professional planners, the answer is an emphatic “No!” And many elected officials would agree, because planning can prevent some of those day-to-day, calendar-crowding problems from occurring in the first place. The entire planning profession is based on the principle that thoughtful, inclusive thinking about problems not only can prevent them but can create better cities and counties in the process. And there is over a century of evidence supporting that claim.

Where did Planning Come from?

To understand the focus and role of planning today, we need to understand where it came from. Here is a very brief summary of the roots of modern city, county, and regional planning.

Aesthetics Roots and the City Beautiful Movement

All large cities require some degree of planning—if only to decide where the roads will go and to prevent houses from being built in the middle of those roads. Large early American cities like Washington, Philadelphia, and Boston were engaged in at least basic planning even before Independence. But many historians link the beginning of the American planning profession to the City Beautiful movement of the late 1800s. Before then, cities functioned—some better than others—but most cities in the young United States could hardly be called beautiful. Most were roaringly ugly and virtually unmanageable. Aesthetics was simply not thought of as a function of local government. But Americans who had traveled and studied in Europe were aware that some cities in the Old World were both functional and beautiful, and they wondered why America should not strive for beauty as well. Our burgeoning pride as a young democracy led to comparisons with ancient Greece, and we had nothing like the monumental architecture that inspired that civilization. As the American economy recovered from the Civil War, this combination of pride and growing economic power led to the City Beautiful movement and the drafting of monumental plans showing what our cities might become.

Nothing captured the spirit of the City Beautiful movement better than the Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair) of 1893. Under the leadership of Daniel Burnham (one of the country’s leading architects) and Frederick Law Olmsted (generally acknowledged to be the nation’s foremost park designer), the fairgrounds on Chicago’s lakefront were transformed into a “White City” of massive venues in classical architectural styles (Fig. 1-1). More than 27 million people—equal to half the U.S. population at that time—visited the fair, and it is a sure bet that most of them had never seen anything like it. Even European visitors could never have seen such an extensive collection of large classical buildings—all covered in gleaming white plaster—in one place. Fairgoers returned to their cities and towns and hamlets with completely different expectations of what a city could be—and aesthetic beauty was a large part of that vision. But beautiful cities don’t just happen; they require plans and then rules to encourage private buildings to fit into the pattern, and so the modern planning profession was born. The seeds sown in the 1893 Exposition still bear fruit today, as manifested by concerns about community character and appearance, good design, open space, and walkability.

Figure 1-1. “The White City” in Chicago in 1893 showcased City Beautiful ideals.

Civil Engineering and Public Health Concerns

During the industrial era American communities faced daunting health problems. Epidemics would periodically sweep cities and towns because of filthy, crowded conditions; tainted water; and untreated sewage. Retrofitting colonial-era cities with clean water systems, and then expanding them to serve a rapidly growing population, required both planning and civil engineering. And the same skills were needed to get rid of sewage in sanitary ways. Once those efforts were under way, good health required that buildings be designed with some way for the residents to access both light and fresh air, and the nation’s earliest building laws focused on those issues. During the late industrial era the advent of the motor vehicle created a need for more and wider streets and highways, and sometimes for the separation of people from heavy traffic. Civil engineers tackled all these issues, and their solutions laid the framework for most American cities. The engineering and public health roots of city planning can still be seen today in concerns about fire access, fire-fighting water supply and pressure, recreational facilities, and the functional efficiency and balance in our transportation systems. Recently, America’s growing concern about the health effects of obesity have led to a renewed interest in neighborhood walkability and connectivity, while concern about rising asthma rates has focused attention on the need to lower pollution from motor vehicles by reducing driving.

The Municipal Reform Movement

Before the 1920s many American city governments were far from honest. Elected officials routinely helped themselves to the “spoils” of elected office—either directly (by misusing public funds) or indirectly (by creating jobs for their friends and family). As Americans became more educated, however, and a strong middle class developed, tolerance for bad government declined. The early years of the 20th century were a time of rapid change in our thinking about how cities should be governed and managed. Americans began calling for professional civil servants, a “scientific” approach to urban management, and even professional city managers who would take day-to-day management of cities (and their “spoils”) away from elected officials. The 1920s saw the flowering of the municipal reform movement, the creation of the city manager form of government, and the introduction of professional accounting practices.

Another part of clean government was having open discussions about where to invest taxpayer money (more roads? more sewers? more parks?) and then accepting competitive bids for the goods and services the city needed to make those investments. That required planning ahead. “Specifications” had to be written so that private companies could make competitive bids to meet them. In addition, in the 1920s the federal government, under the leadership of a bright young secretary of commerce (Herbert Hoover; Fig. 1-2), published two key documents. The Standard Zoning Enabling Act and the Standard Planning Enabling Act were published to encourage cities to think ahead, establish “clean” planning processes, and organize their land uses to avoid “nuisances” and other problems.

Figure 1-2. Herbert Hoover was a key figure in the early legislative establishment of planning and zoning powers.

This reform movement swept the nation, and by 1925 over half the U.S. population lived in cities with zoning—up from just a handful of cities in 1920. All these efforts required planners and engineers. Although the municipal reform movement is now behind us, its legacy has endured, and most of the innovations mentioned above have become so common that we take them for granted.

The Social Reform Movement

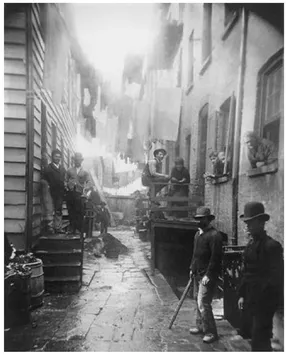

Early planners targeted the appalling living conditions of working people, but as America grew the disparities between rich and poor and among races became more acute and visible. This led to a fourth source of planning—the social reform movement, which blossomed in the 1950s and 1960s. In this movement, reformers were motivated by social critics such as Jacob Riis (How the Other Half Lives; Fig. 1-3) and Michael Harrington (The Other America), and they began to use planning as a tool for social equity. Some of planning’s social-reform efforts, such as large-scale urban renewal, later proved to be misguided, but planning continues to be a potentially powerful tool to reduce inequalities in housing opportunity, promote equal access to community facilities like parks, and protect against the harmful impacts of certain land uses on neighborhoods. Even today, the effects of the social reform movement can be seen in calls for “environmental equity” in the siting of unpopular or difficult land uses (like landfills or maintenance yards for public services). In the past those were almost always placed in poor neighborhoods, but today’s location decisions often take into account the relative concentration of undesired land uses in order to mitigate land-use impacts on the poor.

The Environmental Revolution

While the social reform movement thrived in the 1960s, another revolution in concern for the environment was just getting under way. Beginning with Rachel Carson’s riveting exposé of pollution in Silent Spring, Americans became increasingly aware of the damage our lifestyles and industry were doing to the nation’s air, water, and soils. Ultimately, this led to the

Figure 1-3. “Bandit’s Roost” and the other photographs in Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives were highly influential in heightening awareness of the unsafe and unsanitary conditions in which so many urban poor lived.

passage of the federal Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, and the National Environmental Protection Act before the decade was over, as well as the Endangered Species Act a few years later—each of which imposed obligations on local community planners and engineers. While some communities grudgingly met the challenge to comply with these standards at the local level, many states, cities, and counties went further and passed laws that were stronger than their federal counterparts. One response of the community planning profession was embodied in Ian McHarg’s book Design with Nature, which encouraged Americans to map and understand wetlands, floodplains, soils, hillsides, erosion-prone areas, and vegetation patterns before starting to lay out buildings and roads. This approach has proven so powerful that some form of it is almost invariably included in good large-scale planning efforts, and is sometimes referred to as “McHargian” planning. The first thrust of the environmental revolution was at its strongest in the 1970s, and some of our strongest environmental laws and regulations were adopted during that heyday. But those efforts laid the foundation for our thinking about “sustainability.” Although true sustainability covers much more than the environment, our growing focus on sustainability has brought environmentalism back to the front burner.

Modern planning weaves together all five of these threads into an exciting and essential discipline that helps our communities meet their challenges and achieve their dreams.

Meeting Today's Challenges

The challenges facing U.S. communities are getting harder every year, and the cities and counties that will thrive in the future will be the ones that can understand and reason through those challenges based on their own community values. To get started, let’s list some of the mid-and long-term issues facing America’s communities.

- Demographics. Like many other developed countries, America has an aging population. We form more households, but the average size of those households every year is smaller. The nuclear Mom-and-Dad-and-kids family now represents a minority of U.S. households; never-marrieds, divorced singles, one-parent families, and cohabiting friends now represent the majority. How are we going to transition from a built environment based on larger homes for nuclear families to one built for smaller households, and from a country where everyone drives to one where a large elderly population cannot drive?

- Economics. For the past 20 years, increases in average housing prices have consistently outstripped increases in average wages, and there is every indication the trend will continue. Single-family homes on individual lots are simply becoming too expensive for many households. Even more serious, increased global competition and the rise of Internet business are changing our assumptions about how much commercial and industrial land our cities need. How will we adjust our built environment so that it accommodates new types of jobs and new types of housing that are affordable to our citizens and competitive in the global economy?

- Sustainability. America has long consumed a disproportionate share of the world's resources because it could afford to. But rising competition from China, India, and other countries will make it more expensive to do that in the future. Predictions are that in a few years China will use more oil that the United States (it already uses more concrete and steel) and will demand more food by 2030 than the entire world produces today. As a society, we are facing increased pressure to be more efficient in our consumption of natural resources, to reduce pollution, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and to create sustainable patterns of development so that our children and grandchildren can enjoy the same types of choices and opportunities we have. This will mean doing more to harness the energy of the wind and sun and earth, to conserve water, and to recycle wastes. It will also mean encouraging food production more seriously than we have in the past.

- Efficiency. Roads, transit systems, schools, parks, and utilities cost money—lots of money—but long-term planning can keep those costs down. By coordinating land-use and transportation systems, and by phasing growth to match government's ability to serve it efficiently, planners can ensure that public investments pay for themselves over time. On the other hand, many cities and counties have learned to their dismay that uncoordinated growth can increase taxpayers' costs for capital improvements by 25 percent or more.

- Natural Disasters. Over the past two decades we have seen serious natural disasters affect America's cities and counties with greater frequency and intensity. Examples range from hurricanes Katrina and Rita in New Orleans, to regular flooding along the Mississippi River, to frequent and serious wildfires in Colorado, Texas, Montana, and California. Whether or not these events are caused by long-term climate changes, they pose real-world challenges: How do we improve our ability to protect lives and property from the effects of these types of disasters?

The answer is thoughtful, informed planning. Only through intelligent planning can we understand the interrelationships among demographic trends, global economic forces, environmental systems, and natural phenomena and chart a positive course into the future. Planners are trained to think abou...