eBook - ePub

OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2

Jill Oliphant, Jon Mayled

This is a test

- 332 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2

Jill Oliphant, Jon Mayled

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Structured directly around the specification of the OCR, this is the definitive textbook for students of Advanced Subsidiary or Advanced Level courses. The updated third edition covers all the necessary topics for Religious Ethics in an enjoyable student-friendly fashion. Each chapter includes:

-

- a list of key issues

- OCR specification checklist

- explanations of key terminology

- overviews of key scholars and theories

- self-test review questions

- exam practice questions.

To maximise students' chances of success, the book contains a section dedicated to answering examination questions. It comes complete with diagrams and tables, lively illustrations, a comprehensive glossary and full bibliography. Additional resources are available via the companion website.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2 un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2 de Jill Oliphant, Jon Mayled en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Theology & Religion y Religion. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

AS ETHICS

PART I

1 What Is Ethics?

Essential terminology

Deduction

Definition

Factual statement

Fallacy Logic

Ethics is the philosophical study of good and bad, right and wrong. It is commonly used interchangeably with the word ‘morality’, and is also known as moral philosophy. The study of ethics requires you to look at moral issues such as abortion, euthanasia and cloning, and to examine views that are quite different from your own. You need to be open-minded, you need to use your critical powers, and above all learn from the way different ethical theories approach the issues you study for AS and A2.

Ethics needs to be applied with logic so that we can end up with a set of moral beliefs that are supported with reasons, are consistent and reflect the way we see and act in the world. Ethical theories are constructed logically, but give different weights to different concepts.

However, it is not enough to prove that the theory you agree with is true and reasonable; you must also show where and how other philosophers went wrong.

FALLACIES

With the possible exception of you and me, people usually do not have logical reasons for what they believe. This is especially true for ethical issues. Here are some examples of how not to arrive at a belief. We call them fallacies.

Here are some common beliefs; you may recognise your own reasons for holding a particular view:

• A belief based on the mistaken idea that a rule which is generally true is without exceptions; for example: ‘Suicide is killing oneself – killing is murder – I’m opposed to euthanasia.’

• A belief based on peer pressure, appeal to herd mentality or xenophobia; for example: ‘Most people don’t believe in euthanasia, so it’s probably wrong.’

• A belief in fact or obligation simply based on sympathy; for example: ‘It’s horrible to use those poor apes to test drugs, so I’m opposed to it.’

• An argument based on the assumption that there are fewer alternatives than actually exist; for example: ‘It’s either euthanasia or long, painful suffering.’

• An argument based on only the positive half of the story; for example: ‘Animal research has produced loads of benefits – that’s why I support it.’

• Hasty generalisation: concluding that a population has some quality based on a misrepresentative sample; for example: ‘My grandparents are in favour of euthanasia, and I would think that most old people would agree with it.’

• An argument based on an exaggeration; for example: ‘We owe all of our advances in medicine to animal research, and that’s why I’m for it.’

• The slippery slope argument: the belief that a first step in a certain direction amounts to going far in that direction; for example: ‘If we legalise euthanasia this will inevitably lead to killing the elderly, so I’m opposed to it.’

• A subjective argument that truth varies according to personal opinion; for example: ‘Euthanasia may be right for you, but it’s wrong for me.’

• An argument based on tradition: the belief that X is justified simply because X has been done in the past; for example: ‘We’ve done well without euthanasia for thousands of years, we shouldn’t change now.’

Is–ought fallacy

David Hume (1711–1776) observed that often when people are debating a moral issue they begin with facts and slide into conclusions that are normative; that is, conclusions about how things ought to be. He argued that no amount of facts taken alone can ever be sufficient to imply a normative conclusion: the is–ought fallacy. For example, it is a fact that slavery still exists in some form or other in many countries – that is an ‘is’. However, this fact is morally neutral, and it is only when we say we ‘ought’ to abolish slavery that we are making a moral judgement. The fallacy is saying that the ‘ought’ statement follows logically from the ‘is’, but this does not need to be the case. Another example is to say that humans possess reason and this distinguishes us from other animals – it does not logically follow that we ought to exercise our reason to live a fulfilled life.

AREAS OF ETHICS

Ethics looks at what you ought to do as distinct from what you may in fact do. Ethics is usually divided into three areas: meta-ethics, normative ethics and applied ethics.

1 Meta-ethics looks at the meaning of the language used in ethics, and includes questions such as: are ethical claims capable of being true or false, or are they expressions of emotion? If true, is that truth only relative to some individual, society or culture? What does it mean to say something is good or bad, and what do the words ‘good’ and ‘bad’ mean? (This is studied at A2.)

2 Normative ethics asks the question ‘what ought I to do?’ and attempts to arrive at practical moral standards (or norms) that tell us right from wrong, and how to live moral lives. These are what we call ethical theories. This may involve explaining the good habits we should acquire, looking at whether there are duties we should follow, or whether our actions should be guided by their consequences for ourselves and/or others. There are various ethical theories that are described as normative:

• Teleological or consequential ethics, where ethical decisions are based on the consequences of an action

• Deontological ethics, which is based on duty and obligation

• Virtue Ethics, which is based on the good character of the moral agent (this is studied at A2)

• Ethics based on God-given laws (Divine Command) – see Chapter 6 on Religious Ethics.

3 Applied ethics is the application of theories of right and wrong and theories of value to specific issues such as abortion, euthanasia, cloning, foetal research, and lying and honesty.

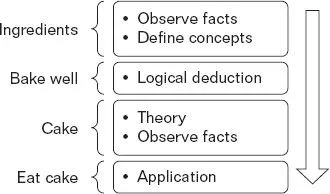

Ethics is not just giving your own opinion, and the way it is studied at AS and A2 is very like philosophy: it is limited to facts, logic and definition. Ideally, a philosopher is able to prove that a theory is true and reasonable based on accurate definitions and verifiable facts. Once these definitions and facts have been established, a philosopher can develop the theory through a process of deduction, by showing what logically follows from the definitions and facts. The theory may then be applied to controversial moral issues. It is a bit like baking a cake.

THE DEFINITIONS OF THE MAIN THEORIES IN NORMATIVE ETHICS

Deontological ethics – certain actions are right or wrong in themselves. Deontological ethics is concerned with the acts that are right or wrong in themselves (intrinsically right or wrong). This may be because these acts go against some duty or obligation or they break some absolute law; for example a deontologist may say that killing is wrong as the actual act of killing another human being is always wrong. Deontologists are always certain in their moral decisions and can take strong moral positions, such as being totally against war. On the other hand they do not take into account the circumstances, or different cultures or different religious views.

Telelogical ethics is concerned with the ends, results or consequences of an action. Followers of teleological ethics consider the consequence of an ethical decision before they act. The action is not intrinsically good (good in itself) but is only good if the results are good – the action produces happiness and love. However, the main problem with teleological ethics is that it can never be sure what the result or consequence of an action might be – it is possible to make an educated guess but not to be absolutely sure, and sometimes we can only tell if the consequences of an action are right with hindsight. Another problem with teleological ethics is that some actions are always wrong, rape for example, and can never be justified by the consequence.

Moral objectivism claims that there are certain universal and absolute values. Modern moral objectivists do not believe that these universal values hold for ever, but they hold until they are proven to be false.

Moral subjectivism claims that moral statements are simply a matter of personal opinion. We simply make our own morality according to our own experiences and see our moral views as true for ourselves or our society and not necessarily applying to others.

Intrinsic good – something is good in itself: it has value simply because it exists without any references to the consequences. This applies to deontological ethics.

Instrumental good – something that is good because of the effects or consequences it has, or as a means to some other end or purpose. To explain this Peter Singer (Practical Ethics, 2011, p. 246) uses the example of money – it has value because of the things we can buy with it, but if we were marooned on a desert island we would not want it.

ETHICAL THEORIES

If we are to have valid ethical arguments then we must have some normative premises to begin with. These normative premises are either statements of ethical theories themselves or statements implied by ethical theories.

The ethical theories that will be examined in this book are:

Utilitarianism: | An action is right if it maximises the overall happiness of all people. |

Kantian Ethics: | Treat other people the way you wish they would treat you, and never treat other people as if they were merely objec... |

Índice

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- How to Use this Book

- Answering Examination Questions

- Timeline: Scientists, Ethicists and Thinkers

- PART I AS ETHICS

- PART II A2 ETHICS

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Estilos de citas para OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2

APA 6 Citation

Oliphant, J. (2014). OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2 (3rd ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1558171/ocr-religious-ethics-for-as-and-a2-pdf (Original work published 2014)

Chicago Citation

Oliphant, Jill. (2014) 2014. OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2. 3rd ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1558171/ocr-religious-ethics-for-as-and-a2-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Oliphant, J. (2014) OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2. 3rd edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1558171/ocr-religious-ethics-for-as-and-a2-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Oliphant, Jill. OCR Religious Ethics for AS and A2. 3rd ed. Taylor and Francis, 2014. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.