![]()

1

IT ALL STARTED WITH ADAM

Adam Smith was a radical and a revolutionary in his time—just as those of us who preach laissez faire are in our time.

—Milton Friedman (Glahe 1978: 7)

The story of modern economics began in 1776.

Prior to this famous date, six thousand years of recorded history had passed without a seminal work being published on the subject that dominated every waking hour of practically every human being: making a living.

For millennia, from Roman times through the Dark Ages and the Renaissance, humans struggled to survive by the sweat of their brow, often only eking out a bare existence. They were constantly guarding against premature death, disease, famine, war, and subsistence wages. Only a fortunate few—primarily rulers and aristocrats—lived leisurely lives, and even those were crude by modern standards. For the common man, little changed over the centuries. Real per capita wages were virtually the same, year after year, decade after decade. During this age, when the average life span was a mere forty years, the English writer Thomas Hobbes rightly called the life of man “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” (1996 [1651]: 84).

1776, A PROPHETIC YEAR

Then came 1776, when hope and rising expectations were extended to the common workingman for the first time. It was a period known as the Enlightenment, what the French called l’Âge des lumières. For the first time in history, workers looked forward to obtaining a basic minimum of food, shelter, and clothing. Even tea, previously a luxury, had become a common beverage.

♪ Music selection for this chapter: Aaron Copland, “Fanfare for the Common Man”

The celebration of America’s Declaration of Independence on July 4 was one of several significant events of 1776. Imitating John Locke, Thomas Jefferson’s proclamation of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” to be inalienable rights, thus establishing the legal framework for a struggling nation that would eventually become the greatest economic powerhouse on earth, and provided the constitutional foundation of liberty which was to be imitated around the world.

A MONUMENTAL BOOK APPEARS

Four months earlier, an equally monumental work had been published across the Atlantic in Mother England. On March 9, 1776, the London printers William Strahan and Thomas Cadell released a 1,000-page, two-volume work entitled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. It was a fat book with a long title destined to have gargantuan global impact. The author was Dr. Adam Smith, a quiet absent-minded professor who taught “moral philosophy” at the University of Glasgow.

Illustration 1.1

Memorial Print of Adam Smith, 1790

“I am a beau in nothing but my books.”

Reprinted by permission of Glasgow University Library.

The Wealth of Nations was the intellectual shot heard around the world. Adam Smith, a leader in the Scottish Enlightenment, had put on paper a universal formula for prosperity and financial independence that would, over the course of the next century, revolutionize the way citizens and leaders thought about and practiced economics and trade. Its publication promised a new world—a world of abundant wealth, riches beyond the mere accumulation of gold and silver. He promised that new world to everyone—not just the rich and the rulers, but the common man, too. The Wealth of Nations offered a formula for emancipating the workingman from the drudgery of a Hobbesian world. In sum, The Wealth of Nations was a declaration of economic independence.

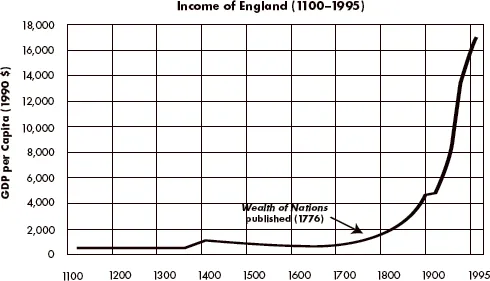

Certain dates are turning points in the history of mankind. The year 1776 is one of them. In that prophetic year, two vital freedoms were proclaimed, political liberty and free enterprise, and the two worked together to set in motion the industrial revolution. It was no accident that the modern economy began in earnest shortly after 1776 (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

The Rise in Real Per Capita Income, United Kingdom, 1100–1995

Courtesy of Larry Wimmer, Brigham Young University.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE ENLIGHTENMENT

The year 1776 was significant for other reasons as well. For example, it was the year the first volume of Edward Gibbon’s classic work, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88), appeared. Gibbon was a principal advocate of eighteenth-century Enlightenment, which embodied unbounded faith in science, reason, and economic individualism in place of religious fanaticism, superstition, and aristocratic power.

To Smith, 1776 was also an important year for personal reasons. His closest friend, David Hume, died. Hume, a profound philosopher, was a great influence on Adam Smith. (See “Pre-Adamites” in the appendix to this chapter.) Like Smith, he was a leader of the Scottish Enlightenment and an advocate of commercial civilization and economic liberty.

THE RUMBLINGS OF ECONOMIC PROGRESS

For centuries, the average real wage and standard of living had stagnated, while almost a billion people struggled against the harsh realities of daily life. Suddenly, in the early 1800s, just a few years after the American Revolution and the publication of The Wealth of Nations, the Western world began to flourish as never before. The spinning jenny, power looms, and the steam engine were the first of many inventions that saved time and money for enterprising businessmen and the average citizen. The industrial revolution was beginning to unfold, real wages started climbing, and everyone’s standard of living, rich and poor, began rising to unforeseen heights. It was indeed the Enlightenment, the dawning of modern times, and people of all walks of life took notice.

ADVOCATE FOR THE COMMON MAN

As George Washington was the father of a new nation, so Adam Smith was the father of a new science, the science of wealth.

The great British economist Alfred Marshall called economics the study of “the ordinary business of life.” Appropriately, Adam Smith would have an ordinary name. He was named after the first man in the Bible, Adam, which means “out of many,” and his last name, Smith, signifies “one who works.” Smith is the most common surname in Great Britain. In fact, Adam Smith’s father was also named Adam Smith, as were his guardian and his cousin.

The man with the pedestrian name wrote a book for the welfare of the average working man. In his magnum opus, he assured the reader that his model for economic success would result in “universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people” (1965 [1776]: 11).1

It was not a book for aristocrats and kings. In fact, Adam Smith had little regard for the men of vested interests and commercial power. His sympathies lay with the average citizens who had been abused and taken advantage of over the centuries. Now they would be liberated from sixteen-hour-a-day jobs, subsistence wages, and a forty-year life span.

ADAM SMITH FACES A MAJOR OBSTACLE

After taking twelve long years to write his big book, Smith was convinced he had discovered the right kind of economics to create “universal opulence.” He called his model the “system of natural liberty.” Today economists call it the “classical model.” Smith’s model was inspired by Sir Isaac Newton, whose model of natural science Smith greatly admired as universal and harmonious.

His biggest hurdle would be convincing others of his system, especially legislators. His purpose in writing The Wealth of Nations was not simply to educate, but to persuade. Very little progress had been achieved over the centuries in England and Europe because of the entrenched system known as mercantilism. One of Adam Smith’s main objectives in writing The Wealth of Nations was to smash the conventional view held by the mercantilists, who controlled the commercial interests and political powers of the day, and to replace it with the real source of wealth and economic growth, thus leading England and the rest of the world toward the “greatest improvement” of the common man’s lot.

THE APPEAL OF MERCANTILISM

The mercantilists believed that the world’s economy was stagnant and its wealth fixed, so that one nation grew only at the expense of another. The economies of all ancient and Middle Age civilizations were based either on slavery or different forms of serfdom. Under either system, wealth was acquired largely at the expense of others or through the exploitation of man by man. As Bertrand de Jouvenel observes, “Wealth was therefore based on seizure and exploitation” (1999: 100). Consequently, they established government-authorized monopolies at home and supported colonialism abroad, sending agents and troops into poorer countries to seize gold and other precious commodities.

According to the established mercantilist system, wealth consisted entirely of money per se, which at the time meant gold and silver. The primary goal of every nation was always to aggressively accumulate gold and silver, and to use whatever means necessary to do so. “The great affair, we always find, is to get money,” Smith declared in The Wealth of Nations (1965: 398).

How to get more money? First, nations such as Spain and Portugal sent their emissaries to faraway lands to discover gold mines, and to pile up as much as of the precious metal as they could. No expedition or foreign war was too expensive when it c...