![]()

Paradigm shifts

The word paradigm was originally defined by Kuhn (1962) as the views shared by a scientific community but Capra (1996) describes how it is now widely used to describe the concepts, values, perceptions and practices shared by any group of people. Thus a paradigm is learnt from experience of living and working in a community. A paradigm shapes the decisions we make and the actions we take. It determines how we see the world, other people and their behaviour.

Once people have learnt one paradigm they are reluctant to change it. They make such fundamental changes only under the pressure of major events. Thus a paradigm shift is a revolutionary break with an established way of viewing the world. Many parts of the construction industry face just this kind of pressure as rapidly changing technology leads to new demands from customers.

Information technology is changing the nature of most human activities. This means that the construction of different buildings and other facilities to accommodate the new kinds of behaviour is needed. The concept of an ‘intelligent building’ is already changing the way buildings are used; internal comfort conditions can be matched to the changing needs of users throughout the day. Similarly there is serious research into the feasibility of continuously monitoring urban environments to help traffic flows, policing and the emergency services, and care in the community.

The construction industry has to respond to these demands for new and more sophisticated products. However, more fundamentally, new technologies are consistent with different ways of manufacturing that rely on cooperative, long-term relationships. The new methods deliver significantly better value, faster and more reliably than traditional methods. This potential was first exploited in Japan because the new technologies fit their cooperative, group culture. The advantages first became evident internationally in the car industry where Japanese products justifiably gained a reputation for providing better quality and value. In response Western car firms adopted the Japanese methods which are now commonplace in all main manufacturing industries. They already influence the leading edge of construction practice.

The main reason for this change is that most of the construction industry’s major customers face pressures in their own businesses caused by these global changes. Customers have been forced to change the way they think about their businesses and the way they work. It is therefore not surprising that many of them expect the construction firms they employ to adopt similar new and more efficient methods. Recent research into leading practice makes it apparent that adopting such methods requires the construction industry to think differently about its work; that is, to make a paradigm shift.

Collapse of the management paradigm

It is significant that changes similar to those becoming evident in parts of the construction industry are already sweeping through many other industries in the West. This has happened because the assumptions on which Western managers have traditionally based their working methods produce inefficiencies wherever they are applied. The results have become increasingly unacceptable to customers. Slow deliveries, poor quality, high prices and broken promises are no longer tolerated. As a consequence, managers in every industry have been forced to make fundamental changes in the way they work. To do this they had to think about their work in a different way. In other words they made a paradigm shift.

The nature of the widespread change in management practice is described in a great mass of new books. For example, Locke (1996) describes the collapse of the American management mystique. He argues that the strengths of American-style management are no longer relevant. Its key features, analysing problems, giving instructions to subordinates and dealing with conflicts, provide an inadequate basis for dealing with today’s world. Locke argues that hierarchical, top-down approaches need to be replaced by more inclusive, cooperative approaches of which Japanese-style management is the most widely quoted example.

Essentially the same case is argued by Lazonick (1991) who traces the development of management from its origins in the market-based, proprietary capitalism that emerged from the British industrial revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its fundamental idea is encapsulated in Adam Smith’s invisible hand. This is the belief that if everyone pursues their own interests, the market will ensure the best outcomes. The naivete of this view became obvious as markets grew larger and technology became capital-intensive.

Market-based, proprietary capitalism gave way to managerial capitalism in a paradigm shift that occurred in the early years of the twentieth century. America invented management as a distinct responsibility and used its strengths to set up large hierarchical structures to plan and coordinate vertically integrated and mechanized production processes. Chandler (1977) chronicles this second industrial revolution which led to mass production guided by what he accurately calls the visible hand of managerial decision making. This has provided unprecedented riches for those lucky enough to live in developed countries. However, work designed and controlled by managers has become increasingly unattractive to affluent and well educated workers. It is also slow to respond to today’s rapidly changing technologies and markets. The inevitable tensions limit what managerial capitalism can deliver and so the way was prepared for another revolution in production methods.

The new approach emerged first in Japan and, since the early 1980s, Japan has outperformed America in the production of consumer durables. This has been most noticeable in the production of motor cars, the twentieth century’s most important industry, and electronic equipment, which is already of major significance in every aspect of our lives and is likely to be the crucial industry of the twenty-first century.

Japan’s success is based on what Lazonick (1991) called ‘collective capitalism’. This relies on cooperation between tightly knit groups of firms. Decisions are made by consensus in networks that spread throughout multi-firm organizations and which include customers and suppliers. Government, too, is often deeply involved in the decision making of these cooperative networks.

Even more recently, the leading edge of international trade has become dominated by computer-based service industries centred on the USA which, as a result, has enjoyed a remarkable period of economic growth in the second half of the 1990s. Software and its many applications has become more significant in creating new businesses than has manufacturing. Construction, although it needs to add sophisticated services to its products, remains primarily a manufacturing industry. Hence the important lessons for the UK construction industry come more from Japan’s strengths in manufacturing than the USA’s strengths in software and service industries. Amongst the major developments in manufacturing, the identification of lean production is particularly important in understanding what needs to happen in the construction industry.

Lean production

Womack et al. (1990) describe in fine detail the move from traditional American management to Japanese cooperation at the leading edge of the motor car industry. They call the new approach ‘lean production’ because of the central importance placed on identifying and eliminating waste. They define waste as processes that add no value for customers. Japanese firms use lean production in their highly efficient production of motor cars that customers find increasingly attractive. Womack et al. explain how first Toyota, and then the other major Japanese car producers, brought their workforce and then their customers and suppliers into their decision making processes. In so doing so they abandoned the American model of hierarchical management in favour of an entirely new approach that relies on building cooperative long-term relationships. The resulting lean production now dominates car production throughout the world.

Fundamental changes of this magnitude take place when conditions are right for the new approach. Given the right conditions, the change is self-reinforcing as the new approach sustains the factors that allowed it to emerge in the first place. This is now evident as the emergence of global markets and rapid developments in technology, especially information technology, are first causing and then reinforcing fundamental changes in management practice. The developments allow major firms to search for the lowest-cost reliable suppliers, wherever they happen to be based, so that much basic work has been moved offshore away from developed countries. In these same firms, layers of middle managers formerly employed in routine information processing have been made redundant by information technology. So those that remain are engaged in far more communication, most of which takes place through the Internet, mobile phones, faxes, video conferences and other devices handling digital data. Head offices are much smaller and many firms own little except information and networks of contacts.

These ways of working miss the unspoken but important messages that come from body language and other aspects of old fashioned face-to-face communication. So managers need new skills in building more secure relationships that can function at a distance. Therefore, ideas about cooperation and trust have become widely discussed. Managers have to recognize when work needs face-to-face relationships; hence the wide use of workshops, project offices and other arrangements that bring teams together to tackle specific, difficult problems.

This coincidence of multi-faceted, self-reinforcing changes which affect many aspects of a community and its work is evidence of what is properly called a paradigm shift. The specific change described in this book is reinforced by fundamental changes in the way science views the world. This scientific revolution has emerged over the past century but its key ideas have broken through into popular literature only very recently. These scientific ideas call into question many of the assumptions that underpin the management paradigm. Also the ideas suggest new patterns of working that are more in tune with human nature and the world we inhabit than any traditional management-based approaches.

A new view of the world

Over recent decades science has built a picture of the world and our relationships with it which is very different from that which provides the intellectual basis for the methods and institutions used by managers in Western, market economies. As these new ideas are understood and discussed outside of the scientific communities, they are giving rise to new theories about management. Some of the theories anticipate and reinforce changes already taking place in practice.

The key ideas of the new view are that our world consists of richly interconnected networks in which ideas of hierarchy are human projections not justified by the structures and processes found in nature. Competition is not the main driving force of change and evolution; it is the exception and generally provides an unsustainable basis for any species. Cooperation is much more widespread and important in explaining the evolution of life on Earth. As Dawkins (1986) puts it, life depends not on the survival of the fittest but of the ‘fittingest’, by which he means that the species that have survived are the ones able to cooperate best with their environments. Capra (1996) uses this new view of the world in explaining how cooperation and symbiosis have been central to the evolution of life on Earth.

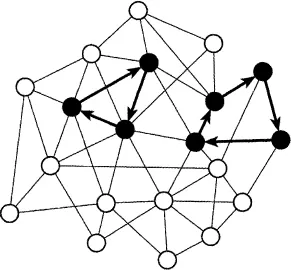

Science now sees the world, including all living creatures, as one incredibly complex system of networks in which feedback loops give the whole and individual parts the power of self-organization. The properties of every part of this vast web are determined by other parts with which they interact. Figure 1.1 illustrates in a greatly simplified form the general nature of this view of the world.

Figure 1.1: Network with feedback loops

Interdependence influences all the interactions between humans and the environments in which they live which, of course, includes other human beings. What this means is that the world we experience is determined by what we choose to regard as distinct things or events and our perceptions of them. We experience not nature, but nature as defined by our method of perception. Other species experience a different world because their perceptions are different. They literally see things we cannot see, hear things we cannot hear, smell things we do not know exist, and so on. Equally we see, hear, touch, smell and taste things that other species are unaware of.

In a similar way other human cultures experience a different world from ours. These differences are reflected most completely in the languages used to communicate. This is true for cultures based on r...