![]()

PART I:

CONFLICT AS A SOCIAL PROBLEM

![]()

A Systems Model for Solving Problems

INTRODUCTION

Social work has been described as a profession that engages in solving social problems and in resolving conflicts (Parsons 1988). We might do well to remember that problem solving and resolving conflicts can produce both positive and negative outcomes. Some social workers, like physicians, intervene in order to lessen inadequate (or “sick”) behaviors and to help the sufferers become cured of them. Other social workers see problems and conflicts as opportunities for growth, or as leverage for bringing about desirable change.

We will try to define both topics in this opening chapter. First, let us look at social problems and what is usually meant by the term ‘problem solving.’ We will do the same for “conflict’ later in this chapter.

LOOKING AT PROBLEMS

In order to bring the above two perspectives together, we might define problem solving as an activity in which a person or group:

- focuses on a human or social condition that is considered incomplete or normatively unacceptable;

- is dissatisfied with or disturbed by this incompleteness; and

- feels ready to make an extra effort in order to try to remedy the situation–that is, to bring or return it to a condition of completeness or acceptability.

For example, perfectly normal people who want to improve their chess-playing skills often sit at home and practice solving chess problems. Similarly, welfare ministry bureaucrats, dissatisfied that a large percentage of our population lives in poverty, have designed programs of neighborhood renewal. Those problematic situations that do get attention are seen as challenges rather than pathologies. They trigger emotional or value-laden responses that motivate us to do something about them, and we become willing to participate personally in solving a problem or resolving a conflict (Rosenheim 1976).

Problems may arise from at least two types of causes. The first type, like hunger or jealousy, is based on a lack of something essential (e.g., food or love). In social work, such problems are labeled “needs.” Solving such problems may seem relatively easy. They can often be eliminated by supplying what is missing. Just as adoption is a solution for orphaned children, income is the answer for unemployed breadwinners and schools are an antidote for illiteracy. In many Western countries during this century, social services were created to take care of unmet needs of citizens caught up in rapidly urbanizing and industrializing societies. Since social services try to supply what a person or system lacks, these personnel operate from a position of relative strength.

A very different type of problem is caused by the accumulation of unwanted surpluses. Thus, problems such as overweight, lung congestion, or violence are caused by eating too many sweets, breathing industrial wastes, or the proliferation of gang wars. Such problems are usually seen as negative –so much so that the causal factors must be stopped or modified if the problem is to be solved. This may require the problem solvers to fight against very powerful vested interests that profit from preserving the status quo. Here, the intervenor is likely to become engaged in confrontation.

Both problems arising from scarcity (e.g., lack of income and skills in impoverished neighborhoods) and those caused by unwanted surpluses (e.g., growing violence in an inner-city slum) can be seen as either pathologies to be treated or as challenges to be solved (and perhaps prevented). In either eventuality, solving social problems is very complicated (Rittel and Webber 1973). Problems are often hard to define, and their causality may be unclear (i.e., multiple). People stop working on problems when they run out of time or money, rather than because they have solved them.

The presenting problem may itself be the outcome of another unsolved problem. Often, discrepancies can be explained in a number of ways, and zero-sum solutions (where somebody wins at the expense of others) come back to haunt us. Solutions for social problems are seldom right or wrong, but rather are judged by how well they lessen suffering or satisfy needs under specific interactional or environmental conditions. Sometimes the adequacy of a solution is judged by how well it conforms to the goals or values of the ruling (local) political party.

A PROBLEM-SOLVING MODEL

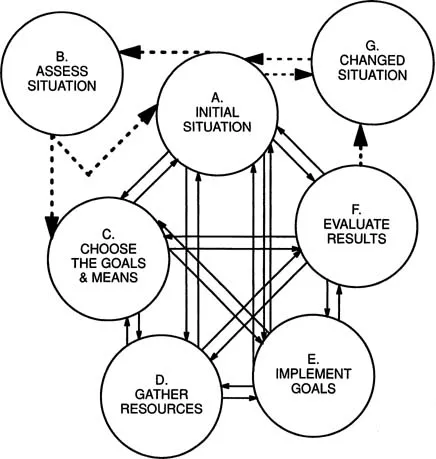

Figure 1.1 shows how problem solving in the helping professions can involve us in a seven-phase model.

A. Initial Problem Situation

At the start, the model articulates the nature of the initial problem situation (which may or may not include conflict). We could, for example, focus on a teenager who is already getting into trouble as a result of her growing addiction to drugs, or on a group of parents from a middle-class neighborhood who fear for their children's safety when the children cross a high-traffic road on their way to school. We usually supplement our initial understanding of the problem situation with a subprocess of objective information-gathering and direct observation.

B. Clarifying the Causes of the Problem

Before taking action, professional persons enrich their efforts with theory-derived knowledge or models of why people or groups behave as they do. With a daring guess (or hypothesis), we are now required to assess whether the drug addict is, for example, suffering from blocked opportunities or from neglectful parents. Similarly, we could verify that street crossing is dangerous for inexperienced

FIGURE 1.1. A Problem-Solving Model

nursery and first-grade children. With such a combination of facts and theory, we identify factors that cause the problem or make its solution urgent.*

C. Choosing Goals and Means

Once a hypothesis regarding causality is formulated, we must establish action goals. Although we want the goals to be logical outcomes of the problem to be solved, goal determination is often constrained by the expressed desires of those suffering from the problem, by our own professional values, by the resources available, and by our awareness of community or societal priorities. In every case, we expect goals and means to remain intertwined and compatible.

So, after as much preparation as possible, we must decide what we intend to do about the problem and what interventions are likely to bring about the desired change. We can decide:

- to do nothing;

- to try to rehabilitate the sufferers and/or their families-perhaps through casework counseling;

- to do crisis intervention by operating a telephone hot-line;

- to try to prevent specific problems from developing altogether (e.g., run an afterschool club program rather than have kids play on the streets, where they are all too often enticed into using drugs); or

- to strengthen healthy behavior of normal children (e.g., by sending them to summer camp).

We are likely to favor goals that can be implemented inexpensively and with minimal opposition.

Since goal setting includes recommending the most effective method we know for intervening, we might decide to help an addicted teenager receive rehabilitative treatment (correction personnel might also want her to be punished). For the parent group, we might include raising funds to make possible the implementation of a safety education program at the school and the installation of a traffic light (or a pedestrian overpass), so that the children can cross the road safely. If implementing these interventions do not pose special budgetary problems, they are likely to be approved (see phase “E”).

Goal and method determination, important as they are, are not enough. The process must include making the goals operational, so that project outcomes can be evaluated. Appropriate change-targets are to be specified, and criteria are determined for judging (in the future) whether the goals have or have not been attained. For example, we may decide that local delinquency is due to lack of supervised free-time settings for children of working parents. If, as the method of intervening, a local elementary school opens a youth club for its pupils during the after-school and early-evening hours, criteria of its success might include:

- Children from many classrooms and from the surrounding neighborhood become members, and renew their memberships after one year;

- The total number of members increases over a specific time period;

- The children find club activities attractive, show signs of having fun, and even suggest additional activities for their group;

- Statistics indicate a lessened incidence of delinquent behaviors (e.g., less noise, fights, property damage, drug use) in the neighborhood;

- The club proves so popular that, upon request, its doors are opened to population groups like retirees, during the morning hours when the children are in school;

- The club opens a well-attended junior-leaders training program, and its graduates start social clubs for younger children who would otherwise play on the streets (and most likely get into trouble); and

- Extension versions of the club program start up in apartmenthouse basements or unused public shelters, and visitors from other parts of the community duplicate the model in their school districts.

After a predetermined period of time, objective evaluators will be able to determine whether the above conditions were or were not brought into existence (see phase “F” in Figure 1.1).

D. Gathering and Preparing Resources

Once goals have been determined philosophically and operationally, phase “D” (see Figure 1.1) can begin. Both the client and action systems, being as creative and efficient as possible, gather together the resources necessary for implementing the strategies and technologies identified in phase “C.” They might apply for a grant from a charitable fund, ask for contingency funds from their municipality or a governmental ministry, or decide to pool resources with a number of social services. Since few projects depend on one set of resources alone, project staff may also be required to function as coordinators of the resource providers. The staff will also be responsible for reporting to the donors how each particular donation was to be used.

E. Taking Action to Implement the Plan

Once the resources have been located, the staff begin to act – hopefully in accordance with the systems' goals. Professional and administrative persons use resources to produce desired changes in themselves or in others within a relatively short period of time. During this implementation phase, records should be kept of all intervention efforts and outcomes, until (and even after) the change goals are reached. A formal monitoring (in writing, statistics, or videos) of decisions made and of actions undertaken is part of sound implementation.

F. Evaluating Results

After the intervention methods have been operational for a designated period of time, a process of outcome evaluation (phase “F”) should take place. Data about the current situation must be studied and compared to the goal statements made in phase “C.” If the young lady remains clean of drugs after completing her rehabilitation program, we might infer that her problem has been solved. If there is a significant drop in delinquency generally and in drug use specifically, our after-school program is worth continuing.

Similarly, if no children have been involved in car accidents on their way to and from school after a full year, it would seem that the problem has been solved. Evaluation might also reveal whether the children had learned about safety in a cognitive way, or whether they had internalized new skills that enable them to recognize and avoid traffic dangers.

Evaluation could focus both on whether a problem has been solved successfully and on whether the solution was efficient or expensive.

G....