![]()

PART ONE

An overview of the circular economy

![]()

01

The circular economy

What is it?

Every few hundred years in Western history there occurs a sharp transformation. Within a few short decades, society – its world view, its basic values, its social and political structure, its arts, its key institutions – rearranges itself. Fifty years later there is a new world.1 peter f drucker

The feted business consultant Peter Drucker, writing in 1992, went on to say: ‘And the people born then cannot even imagine the world in which their grandparents lived and into which their own parents were born.’

In recent decades, we can see many transformational changes in the way we live, work and communicate. The linear economy that emerged from the early industrial revolutions, based on take, make and waste, is being replaced by the circular economy. Companies will rethink how they design laptops, furniture, sneakers, cars, mobile phones, cleaning products and even jeans. Instead of selling and forgetting products, companies will use products as opportunities for continuous value creation and profitable, long-term customer relationships.

Stahel and others describe different business models in the circular economy.2 I do not own a mobile phone, instead I lease it from a company that has designed it to be upgradeable, customizable and easy to repair or remanufacture. I no longer buy electric lights, I buy LED lighting as a service, and the company selling that lighting service ensures those LED lamps work reliably for a very long time.

Businesses large and small, around the world – established global corporates, and disruptive start-ups – are innovating business models and product design, aiming to capitalize on the fantastic opportunities to trade with the rapidly growing ‘consumer classes’, secure access to future resources, and ‘future-proof’ their businesses.

We review the issues arising from our traditional ‘linear’ economy in Part 2, but first we explore the circular economy in more depth, looking at:

- the background to the circular economy;

- evolution of the concept: main schools of thought, their principles and how these compare;

- a brief look at some supporting approaches;

- scaling it up: a selection of business groups and companies investing in it;

- a generic framework, which we explore in more detail in Chapters 2 to 4.

Background

From the 1970s onwards there has been increasing realization that many of the resources we rely on for our survival are either finite or are constrained by the speed of renewal, or availability of land. In our urban environments it is easy to forget that the earth and its living systems provide everything we use or consume – our food, air, water, housing, clothes, transport – everything.

Rachel Carson, in her book Silent Spring (1962), raised public awareness of the environment and destruction of wildlife through widespread use of pesticides.3 The press condemned her, and the chemical industry even tried to ban the book. Since the 1950s, agricultural practices have changed in many developed nations, using synthetic fertilizers and irrigation to achieve massive increases in crop yields. Alongside this, human population continued its exponential growth path, with increasing numbers of people and levels of consumption. In the 20th century, whilst population quadrupled, gross domestic product (GDP) and consumption increased by a factor of 20. Many other indicators of consumption and development show the same exponential upward trend from the 1950s, with Figure 1.1 showing some examples of the ‘Great Acceleration’. As the effects of the ‘Great Acceleration’ began to emerge, scientists and institutions began to question our ‘traditional’ ways of selling and consuming products. You can see more on the World Economic Forum website.4

Economist and systems theorist Kenneth Boulding described the issues of open and closed systems in relation to economics and resources.5 He speculates whether the first factor to limit growth would be running out of places to store our waste and pollution, before we ran out of raw materials to use. ‘Los Angeles has run out of air, Lake Erie has become a cesspool, the oceans are getting full of lead and DDT, and the atmosphere may become man’s major problem in another generation, at the rate at which we are filling it up with gunk.’ He advocated focusing on maintaining our resource stocks and encouraging technological change to reduce production and consumption.

Figure 1.1 The Great Acceleration

SOURCE: Stockholm Resilience Centre [Online] http://stockholmresilience.org/21/research/research-news/1-15-2015-new-planetary-dashboard-shows-increasing-human-impact.html/

As we improved techniques for mining, extraction and manufacturing, resource costs declined steadily, despite some short-term increases resulting from wars and geopolitical factors. Over the 20th century, prices halved. As we moved into the 21st century, a tipping point occurred, and the declining trend became a steep upward trajectory that consultants McKinsey described as a ‘century of price declines, reversed in a decade’.6 We have found, and used, all the ‘easy to get at’ stuff. Worse still, prices are at their most volatile since the ‘oil shock’ of the 1970s, and frequently a shock in one resource flows through to others.

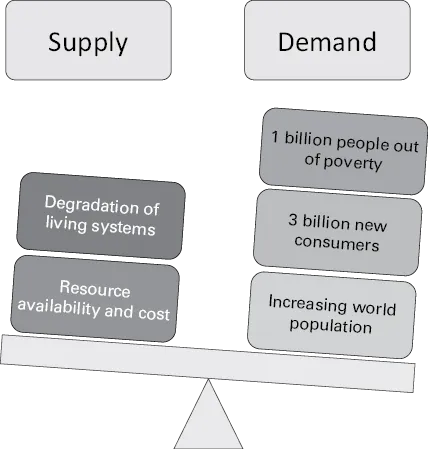

Predictions show a step-change in global demand between 2010 and 2030, as 3 billion new consumers join the ‘middle classes’, earning enough income to purchase a mobile phone, more processed food and meat, better housing and maybe even to take holidays abroad.

This rapid growth in demand, plus the difficulties of finding cost-effective sources of materials and meeting environmental challenges, puts a further squeeze on the cost of supply. We still have a major challenge with inequality and poverty too, with over 1 billion people lacking secure access to food, water and energy. Figure 1.2 highlights the tipping point we have reached. The increasing pressures of demand, coupled with challenges for supply of resources, and the health of the living systems we depend on for clean air, safe water, food, timber, pollination and medicine, mean we need to rethink our systems. We explore this further in Part 2.

Reports in recent years from the United Nations, the European Commission, the OECD, the World Economic Forum and global management consultancies have echoed the strong warnings published in the Club of Rome’s report Limits to Growth in 1972.7 They share concerns about the combination of overexploitation of important ecosystems and natural resources, an increasingly unstable climate, and pollution of air, water, soil and the atmosphere.

The way we make things is contributing to the problem. Most manufacturing methods are ‘linear’ – the company takes some materials, makes a product and sells it to the consumer, wh...