eBook - ePub

Middle East

Geography and Geopolitics

Ewan Anderson

This is a test

- 360 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Middle East

Geography and Geopolitics

Ewan Anderson

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Middle East is a lively and much-needed update of a well-respected work. Based on W. B. Fisher's book of the same name published in 1978, Anderson provides a comprehensive account of the physical geography which has been so instrumental to the make-up of the geopolitics of the region. The book also covers the sociology, religion, society and economy of the region.

With comprehensive illustrations and maps, it provides an excellent synopsis and critique of the complexities which have made this an intriguing and important regional geographical study.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Middle East un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Middle East de Ewan Anderson en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Sciences physiques y Géographie. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1 Introduction

Since the Second World War, the Middle East more than any other global region has been the focus of international attention. This high profile has been evident for a number of reasons. The Middle East has a central location in the World Island at the meeting place of the three Old World continents. Situated at the major crossroads of global cultures, it is hardly surprising that the Middle East has been the scene of conflict throughout time.

During the modern period, two key factors have become superimposed upon this long-established pattern to ensure that the Middle East remains the world’s premier geopolitical flashpoint. The first factor was the establishment of the state of Israel centrally in the Arab core of a region which is overwhelmingly Islamic. The second factor was the realization that between them certain Middle Eastern states possessed the world’s major reserves of petroleum. Since petroleum is generally considered to be the most strategic commodity and the one upon which the only truly global industry has developed, the unique geopolitical significance of the Middle East is clear. Over the medium term at least, there is likely to be an increasing dependence for oil upon a region which is seen as among the most volatile. However, suffice it to say that there are probably as many misperceptions as there are accurate perceptions about the Middle East.

Misperceptions arise because of the innate mystique of a region apparently dominated by two things foreign to the Eurocentric viewpoint: an extreme climate characterized by aridity and Islam. Furthermore, until recently, for a variety of reasons, very few from the Western world had travelled at all extensively throughout the Middle East. Even today, only Turkey, Egypt, Israel and to a far lesser extent Jordan among the countries of the region have developed tourism on any scale. Even in those four states, most visits are limited to a relatively small number of globally acclaimed sites. Thus, very few people in the West are familiar with the Middle East and able to make rational judgements from experience. To the many, the region remains a problem, possibly the problem, in international relations.

Given the reality of the diversity within the Middle East, a more fundamental issue is the fact that, even among experts, the exact definition of the region remains unclear. From the Great Age of Discovery in the fifteenth century, it had increasingly become customary to distinguish between the Near East and the Far East. The Near East comprised essentially the eastern Mediterranean and adjacent lands while the Far East was everything east of India. The Indian subcontinent was in terms of trade and military strategic thought the centre of the British Empire and was, other than its most northerly and westerly approaches, accepted as a separate entity located in the East but not the Near East or Far East. Thus, the area in the middle, the Middle East, was almost by default that lying between the Indian subcontinent and the Near East or Levant. Geographically, therefore, there is some logic in the designation of what is now considered the Mashreq as the Middle East. However, this area accounts for only part of the modern region, the basis for which was geopolitical rather than geographical.

Although the term Middle East probably had currency in the British India Office during the 1850s (Beaumont et al. 1988), for its introduction into accepted terminology credit is normally given to Alfred Mahan, the American geopolitical historian. The focus of the Middle East as he envisaged it was the Persian-Arabian Gulf. It has been variously interpreted that Mahan saw this area as ‘middle’ in an east–west sense but also possibly in a north-south sense, essentially between the Russians to the north and the British to the south.

It was, however, with the dawn of the age of global warfare that the Middle East was distinguished as crucial in grand strategy. In the First World War, the operational area of the Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force was considered the Middle East while that of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force was characterized as the Near East. Until the end of the First World War therefore, geographical and geopolitical definitions tended to coincide.

Between the wars, the Middle Eastern Command and the Near Eastern Command of the Royal Air Force were amalgamated under the title of the former. This precedent was followed by the Army which, at the beginning of the Second World War in defence of the Suez Canal in particular, established its GHQ Middle East in Cairo. Effectively, a military province stretching from Iran to Tripolotania was created and named Middle East. The importance of the region, and in particular its political and economic life resulted in the appointment of a Minister of State and the development of an economic organization, entitled the Middle East Supply Centre. The Centre was originally British but later Anglo-American and thereby the term Middle East became generally recognized not only in the Eurocentred world but also in the home of its originator.

After the Second World War, the territorial designation adopted by the military authorities continued and Middle East became the standard term of reference, exclusively used in numerous government publications summarizing political events, territorial surveys and schemes of economic development. An additional possible explanation for its incorporation into official terminology has been advanced in The Middle East (1978) by Fisher who suggests that France had strong military claims in an official Near East theatre of war, but fewer in a Middle East, which was therefore much employed as a term and extended as a geographical concept when the situation of France vis-à-vis Britain became equivocal in 1940–41. This idea may or may not be valid but it is clear that over the post-war years, the term Near East, so redolent of Balkan Europe in the nineteenth century, has faded from common usage. Its connotation in geographical terms was always vague if rather more exact than that of Middle East.

Throughout the vicissitudes of the Cold War, the Middle East remained central in the concerns of East and West. Both the USA and the Soviet Union developed close relationships within the region while some states, such as Egypt, changed sides. As a result, the term Middle East has become sanctioned by use world-wide, including within the region itself. Nonetheless, while the geopolitical concept of the Middle East has become relatively clear-cut, the geographical boundaries do not enjoy universal recognition. In the USA, the State Department has compromised by using the term Near and Middle East. In the US military, the region is divided between three Commands, the European, the Middle Eastern and the African. However, it is reasonable to conclude that the major problem of delimitation concerns the states of North Africa. As a result, in many volumes the term ‘Middle East and North Africa’ is used as a unit.

As with regional geography in general, there is little difficulty in defining the core, it is the boundaries which cause problems. The Mashreq is tightly integrated into the core but the Maghreb stretches westwards as far as Mauritania. Neither geographically nor geopolitically could Mauritania be considered Middle Eastern. Therefore, an appropriate division would seem to be between the states predominantly of the desert and those of the Atlas Mountains and beyond. Libya is accepted as a state of the Maghreb but it would appear to have more in common with Egypt including shared aquifers. Other issues of definition concern Sudan, the southern part of which is clearly more closely associated with Central Africa than the Middle East. Nonetheless, Sudan is a Nile Valley state and there is historical and geographical integration with Egypt. A small but highly significant area of Turkey is technically within Europe but few would doubt that the culture of the state places it firmly within the Middle Eastern setting. The other contentious issue concerns Cyprus because of its dominant Greek connection. However, the island is located geographically within the Middle East and, since partition, its links with Turkey have been strengthened.

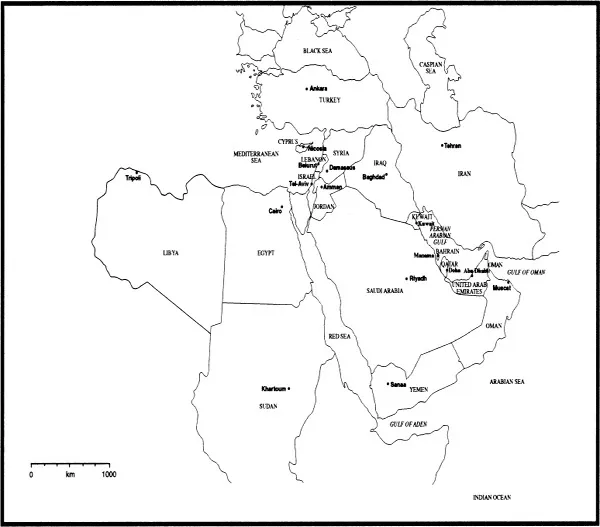

Therefore, in this volume, following the pattern established in The Middle East (Fisher 1978), the Middle East is taken to include all the generally accepted states together with Libya, Sudan and Cyprus (Figure 1.1). However, it should be noted that in discussing physical landscapes and in particular historical developments, there are several useful terms which predate the modern mosaic of states and, where appropriate, these have been retained. They include Levant, Mesopotamia and Asia Minor.

Figure 1.1 Middle East states and capitals.

These terms, current in earlier periods, provide a reminder of the early importance of the Middle East in which the Egyptian, Sumerian, Babylonian and Assyrian civilizations flourished. Within the region also arose three great monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. A fourth even older, Zoroastianism, arose nearby and spread into the region. The fusion of cultures and civilizations within the Middle East results from the fact that the region was successively part of the Persian, Greek, Roman, Arab, Mongol, Tartar and Turkish Empires (Peretz 1978). As might be expected from its location, the Middle East has been central in human affairs.

By delimiting the region as extending from Libya to Iran and Turkey to Sudan it is possible to postulate the existence of a natural region designated the Middle East on geographical grounds. The region has an unusual characteristic climatic regime which has induced highly distinctive human responses and activities. According to Fisher (1978) in The Middle East, the common elements of natural environment and social organization are sufficiently recognizable and strong to justify treatment of the Middle East as one single unit. However, despite the overall unity of climate and culture, the Middle East, when examined in detail on a smaller scale, reveals enormous diversity. There is frequently a juxtaposition of harsh desert environment and intensively cultivated rich agricultural land or extreme modernity and ancient tradition or extraordinary wealth and grinding poverty.

The modern Middle East is central between Europe, Asia and Africa but it can now be seen as intermediate between the developing and the developed world. The Middle East is on the North-South boundary. Through Islam with its 1.2 billion adherents, it has links to most countries in the world while geographically it abuts on to more different cultures than any other. As a result of oil, it is closely aligned with the three great economic regions: the USA, the European Union (EU) and Asia Pacific. Whether viewed geographically or geopolitically, the Middle East is central and exercises a global influence.

2 Land structure and form

The landscape comprises an underlying structure and a surface form. In the Middle East, large areas of which are totally unencumbered by human artifacts or even vegetation cover, the relationship between structure and form is more apparent than in probably any other major region of the world. The principal fault patterns can be clearly seen, the geological characteristics are relatively obvious and the effects of the major geomorphological processes are clear-cut. However, underlying this clarity is complexity. The foundations have been laid by the tectonic history, the main events of which are on a macro-scale. Given the vast extent of the timescale involved and the global nature of the movements, the finer detail of this must remain to an extent conjectural. On the mosaic of land masses resulting from tectonic activity, the geological sequence has been laid. Through emergence and submergence, drier periods and wetter periods, the stratigraphy varies in time and location throughout the Middle East. In the context of tectonics, these would be considered meso-scale differences. The emergent land mass has then been moulded by geomorphological processes to produce the present landscape. Many of these processes operate on what is, comparatively, a micro-scale. Thus there are broad differences in scale between the events which have occurred in tectonics, geology and geomorphology.

There are also differences in the current state of knowledge about these subjects. Interest in the economic aspects of geology has tended to relegate the more theoretical questions of origins to a secondary role. This situation, however, has improved in recent years particularly following the elaboration of the theory of tectonics, which has special applicability to the Middle East. An improved appreciation of the locations of major faults, earthquakes and volcanic activity has allowed the edges of the plates to be more accurately identified. With regard to the geology, the depth of knowledge across the region varies considerably. In areas with a potential for hydrocarbons, drilling has been relatively intense and there is as a result abundant information about the underlying stratigraphy. This has been supplemented by the growing and pressing requirement for geological data concerned with aquifers. In areas where these interests do not obtain, knowledge is more sparse. However, the situation is being rectified as a result of enhanced survey procedures using, for example, satellite imagery. Furthermore, fundamental research has focused on certain key areas in the Middle East such as the Red Sea Basin and its extension northwards through the Jordan Valley.

Geomorphological research presents rather different problems. To understand the operation of processes in the development of landforms, it is normally necessary to establish monitoring programmes. Much of the Middle East, particularly the hyper-arid areas, is inhospitable for sustained research. Again, improved approaches to surveying have enhanced the situation but many key geomorphological events occur on a small scale and there is no real substitute for fieldwork. For example, while broad patterns of erosional change can be established from aerial photographs or satellite images, the measurements of rates of erosion and the relationship between these and the processes involved can only be established by meticulous field procedures. It remains true that there are less textbooks on arid zone geomorphology than there are journals on glaciology published annually. Essentially, tectonics, geology and geomorphology are intimately related. For instance, tectonic movements can, through emergence and submergence, control the geological succession and through lateral movements induce folding. The thrusting up of fold mountains and the development of faults affects the shape of the landscape and geomorphological processes. Geology, as a result of the permeability, structures and resistance to erosion of rocks, influences the development of landforms.

Tectonics

The basis for the fundamental movements which result in major global features, particularly the distribution of land and sea, is plate tectonics. The surface of the Earth comprises a series of plates, some very large and some relatively small. The movement of these plates results in events at their edges which produce change sufficiently discernible for the broad location of those edges to be identified. The movements take place in the crustal layer and are generated by convection currents produced as a result of differential heating within the mantle.

There are three categories of plate edge effects. Plates may be forced apart by upwelling from the mantle and this movement is termed ‘spreading’. Alternatively, plates may move together, the result being that one plate is compressed against another. One plate is forced below the other and its lower advancing edge is then consumed in what is termed a ‘subduction zone’. Third, two plates may move laterally with respect to each other producing transform faults. Clear-cut examples occur of all three in the Middle East. The central trough of the Red Sea is a zone of spreading while to the north-east, at the other end of the same plate, the Taurus and Zagros mountains indicate a subduction zone. The Jordan Valley represents a transform fault. While there is some variation in interpretation, the conventional large-scale model suggests that for much of its evolution Arabia was part of the African continental plate, the regions of what are now the Taurus and Zagros mountains representing the more active leading edges of that plate (Figure 2.1). The African and Arabian plate drifted northwards to collide with the Eurasian plate, crushing as it did so the sediments laid between the two plates in the Tethys Sea, a geosyncline formed during Triassic-Jurassic times. The Tethys Sea was a vast geosyncline or downfold in which great thicknesses of sedimentary deposits had been formed as a result of erosion of the land plates to the north and south. As these sediments accumulated, they trapped the organic matter which eventually gave rise to the occurrence of hydrocarbons. At the time of the collision, the northern part of Iran lay at the southern edge of the Eurasion plate and the Zagros belt represents the main area originally occupied by the Tethys Sea. Following this a...

Índice

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- Abbreviations and acronyms

- Prologue

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Land structure and form

- 3 Climate

- 4 Soils and vegetation

- 5 Two key resources

- 6 Historical geography

- 7 People and population

- 8 Society

- 9 Economy

- 10 The states of the Middle East

- 11 Geopolitics

- Epilogue

- References

- Index

Estilos de citas para Middle East

APA 6 Citation

Anderson, E. (2013). Middle East (8th ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1596364/middle-east-geography-and-geopolitics-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Anderson, Ewan. (2013) 2013. Middle East. 8th ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1596364/middle-east-geography-and-geopolitics-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Anderson, E. (2013) Middle East. 8th edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1596364/middle-east-geography-and-geopolitics-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Anderson, Ewan. Middle East. 8th ed. Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.