eBook - ePub

From Trauma to Healing

A Social Worker's Guide to Working with Survivors

Ann Goelitz

This is a test

- 284 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

From Trauma to Healing

A Social Worker's Guide to Working with Survivors

Ann Goelitz

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

From Trauma to Healing: A Social Worker's Guide for Working With Survivors is the next significant publication on trauma in the field of social work. Since September 11 and Hurricane Katrina, social workers have come together increasingly to consider how traumatic events impact practice. From Trauma to Healing is designed to provide direction in this process, supporting both the field's movement towards evidence-based practice and social workers' growing need to be equipped to work with trauma. It does so in the practical-guide format already proven to be compelling to social work students, educators, and practitioners, providing case examples, and addressing social workers' unique ecological approach.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es From Trauma to Healing un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a From Trauma to Healing de Ann Goelitz en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Médecine y Psychiatrie et santé mentale. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part I

First Things First

Safety After Trauma

Chapter 1

The Importance of Safety

Social workers need to understand the safety issues that trauma survivors confront. Trauma overrides survivors’ inherent adaptive functions, leaving them helpless and terrified in a world that feels out of control and unsafe. Trauma experiences so sharply affect their physiological arousal, emotions, and memory that at times they have no memory of the traumatic event, but experience intense emotion; or have clear recall with no emotion. Because the emotions generated by the ordeal fall so far out of the scope of human understanding and coping, survivors tend to avoid them, thus cutting themselves off from current experiences as they build a protective shell. This dissociation can be both conscious, as individuals avoid memories of the incident; and unconscious, as they shy away from any emotional experience that triggers unwanted memories.

Trauma recovery requires integration of distressing events and reconnection with daily life. In order to heal, survivors must also learn how to manage symptoms and tolerate feelings associated with trauma (Herman, 1992). Although many integrate their experiences and recover on their own with no intervention necessary, the intense emotions endured as a result of trauma can make integration difficult. Often survivors fluctuate between re-experiencing the trauma via flashbacks and feeling numb as they deny and repress their emotions.

Definitions

- Coping—Process of dealing with difficulties, problem solving, and adapting to the environment in order to manage stress and conflict effectively.

- Dissociation—Disconnection from thoughts, memories, or emotions that provides internal distance from reminders of traumatic events, but also prevents integration of trauma material and disrupts normal psychological functioning.

Instinctual reactions related to the fight or flight response can also become habitual and maladaptive after distressing events if survivors do not restore their sense of safety. This habitual response causes stress, impeding recovery and contributing to trauma’s erosion of survivors’ sense of safety. Healing requires creating a new safety (Rothschild, 2000). The healing process includes attaining physical, emotional, and financial stability.

Definitions

- Flashback—Intrusive and involuntary re-experiencing of traumatic events through images, emotions, or physical sensations.

- Fight or flight response—Physical reaction to perceived threat or danger that leads to discharge of hormones such as adrenalin and cortisol, increased heart rate, shallow breathing, and slowdown of non-essential activities such as digestion so that the body can mobilize to protect itself.

Tune in to Safety

When reading about survivors and hearing their stories in person, some of us may not connect with their loss of safety because we unconsciously distance ourselves from their suffering. Although this is not a healthy approach, it is natural to try to protect ourselves in this way. We need to create a safe space when we work with trauma survivors and it is difficult to do so without first opening ourselves to their emotional experience (Bromberg, 2006). A safe workspace requires witnessing how unsafe they feel, but doing so while grounded in our own safe place. This protects us from secondary trauma and allows us to connect with survivors as we help them.

Definitions

- Safety—State essential to trauma recovery and unique to each individual, in which: 1) risky behaviors, unhealthy relationships, and negative emotions are reduced; and 2) a sense of well-being, trust, calm, and positive coping are increased.

The stories of survivors may seem foreign to social workers who have not experienced trauma. If so, think of your own losses and hardships and the associated feelings. Often we find it easier to relate to the emotions than to the actual events a survivor has endured. For me, September 11 is such a touchstone. I (Ann Goelitz) worked at a hospital not far from the disaster and met with the survivors who came in. I also talked with many more family members in search of their loved ones and with hospital staff and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) workers who helped survivors and family members. I lived in Manhattan, so I experienced the trauma too and had feelings of fright and vulnerability. I dealt with the traumas of the survivors, the families, and the practitioners along with my own personal trauma. I remember going home after long days at work with tears in my eyes. I had difficulty taking good care of myself and wanted to watch the replays on television instead.

The pain of this experience and my own loss of safety help connect me with survivors and their horrific stories. The coping I managed to do to take care of myself at the time and my constant awareness of the need for self-care keep me grounded as I work with survivors. To tune in, connecting with any kind of loss will work. The loss of a loved one, being diagnosed with a serious illness, or witnessing an accident can bring up feelings similar to those of survivors. Try to imagine any time you felt vulnerable and then join it with a familiar feeling of comfort. Together, these emotions allow us to be close to survivors, understanding how unstable they feel, without losing ourselves in the process. This chapter discusses how survivors lose their sense of safety when trauma occurs and explores the need to recreate it in order for survivors to cope with the stress generated by traumatic events. For more information on coping and self-care, see Chapter 7.

Tips

- Tune in to personal loss or trauma—Remember a trauma or loss you experienced or witnessed. Do not pick a raw or unprocessed incident. As you think of it, become aware of your physical, emotional, and cognitive sensations, telling yourself that these are the kinds of feelings survivors encounter. Then think of something safe to balance the loss. Breathe into the safe feeling or use other means to relax and nurture yourself.

The Stress of Trauma

Intense trauma emotions can cause physiological stress. Research has found that emotions affect the body. If repressed during upsetting times, they can become physically trapped, causing individuals to lose contact with both the painful feelings and the body parts holding them. The intestines, for instance, contain an abundance of emotion-regulating neuropeptides and receptors (Pert, 1999). This may explain experiences such as butterflies in the stomach and emotional difficulties that lead to indigestion and ulcers.

Similarly, the immune system operates more efficiently when individuals express, rather than repress, their feelings. Studies have noted better recovery rates in cancer for those who expressed anger. Tumors were also found to grow more quickly when transplanted into rats that were under stress (Pert, 1999). Not only does repressing emotions create stress, but life without access to safe feelings can also relegate trauma survivors to a life of disconnection and isolation. Recovery will not occur until survivors resolve trauma emotions, and integration of emotions must take place in order to heal wounds caused by horrific experiences.

Emotions can be either biologically adaptive instinctual reactions, such as warnings of danger, or learned reactions that are not necessarily adaptive. Reactions to shocking occurrences are maladaptive when they warn of danger that no longer exists or lead to numbing of feelings that are painful to bear. Maladaptive responses include:

- avoidance where survivors stay away from people, places, or activities with no danger because they are reminders of their ordeal; and

- hyperarousal or arousal of the autonomic nervous system, causing tension, an exaggerated startle response, insomnia, and fatigue.

These two features of survivors’ responses to trauma particularly influence their abilities to experience and express emotion (Litz, Orsillo, Kaloupek, & Weathers, 2000). Usually difficult to unlearn even with professional help and medication, these reactions make regulation of affect a feat for survivors (Greenberg & Paivio, 1998).

Definitions

- Avoidance—Individuals staying away from people, places, or activities even when these are not dangerous because they are reminders of trauma.

- Hyperarousal—Heightened emotionality that can lead to agitation, anger, difficulty sleeping, and/or hypervigilance.

- Hypervigilance—State of increased attention to the environment, in order to detect threat and prevent harm, that can increase anxiety, prevent sleep, and cause fatigue.

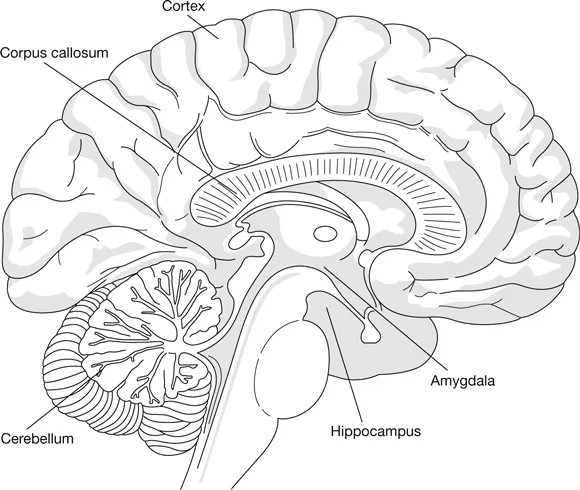

Signs of stress and stress adaptation also present physiologically in survivors’ brains. These include heightened amygdala activity, causing a fear response, and neurochemical, neuropeptide, and hormonal changes, induced by stress and prevented by adaptation (Charney, 2004; Vermetten & Bremner, 2002). The inability to heal, integrate trauma material, and regulate trauma emotions have been linked to continuation of trauma symptoms. This may be related to the cortical processes in the brain. These cortical processes normally store memories in permanent memory as narrative. When the cortical processes break down during distressing events, the brain stores memories as sensory fragments, causing nightmares and flashbacks to persist (Siegel, 2001). The resulting stress erodes trauma survivors’ basic sense of well-being.

The Fight or Flight Response

The fight or flight response triggered by traumatic events can also contribute to survivors not feeling safe. Emotions generated by trauma often deter the recovery process, but can be protective as the trauma occurs, activating the fight or flight response and causing survivors to act quickly to protect themselves and others (Goleman, 1995). Goleman explains these functions of emotions from the viewpoint of the brain. The amygdala monitors affect and connects it to emotional memories. It also controls the fight or flight response, taking over during danger and using feelings such as fear to encourage quick reactions to threats.

This process differs from that of the neocortex, another part of the brain that works actively with emotions. Its response is slower and more methodical. The neocortex essentially “thinks” about how to respond, utilizing cognitive functions such as comparison, analysis, and contemplation, whereas the amygdala acts quickly, without thinking. Both functions are important when processing affect.

Figure 1.1 Parts of the Brain Impacted by Trauma

‘Alcohol and the adolescent brain: Human studies’ by S. F. Tapert, L. Caldwell, and C. Burke, 2004/2005, Alcohol Research & Health, 28(4), p. 207. Copyright S. F. Tapert. Reprinted with permission.

Without the amygdala, no memories would be associated with feelings. Response to danger would also happen slowly. On the other hand, without the neocortex, all responses would be impulsive and lack cognitive control. We could not make decisions without the neocortex’s ability to problem solve and reason. The amygdala’s ability to safeguard us by sensing danger and prompting protective action also plays a role in decision making, contributing to making choices that increase safety during crises. The amygdala uses fear to rush us out of the path of an oncoming vehicle. If we waited for the neocortex’s slower cognitive process, we could get hurt (Goleman, 1995; Greenberg & Bolger, 2001).

With trauma, the fight or flight response dominates while the “thi...

Índice

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: First Things First: Safety after Trauma

- Part II: Important Considerations

- Part III: Tools for Surviving Trauma

- Part IV: The Survivor’s Experience

- Part V: Potentially Traumatic Events

- Part VI: Direct Interventions for Social Workers

- Part VII: Working in the Community

- References

- Index

Estilos de citas para From Trauma to Healing

APA 6 Citation

Goelitz, A. (2013). From Trauma to Healing (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1608669/from-trauma-to-healing-a-social-workers-guide-to-working-with-survivors-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Goelitz, Ann. (2013) 2013. From Trauma to Healing. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1608669/from-trauma-to-healing-a-social-workers-guide-to-working-with-survivors-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Goelitz, A. (2013) From Trauma to Healing. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1608669/from-trauma-to-healing-a-social-workers-guide-to-working-with-survivors-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Goelitz, Ann. From Trauma to Healing. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.