1

On Time Preference, Government, and the Process of Decivilization

TIME PREFERENCE

In acting, an actor invariably aims to substitute a more satisfactory for a less satisfactory state of affairs and thus demonstrates a preference for more rather than fewer goods. Moreover, he invariably considers when in the future his goals will be reached, i.e., the time necessary to accomplish them, as well as a good’s duration of serviceability. Thus, he also demonstrates a universal preference for earlier over later goods, and for more over less durable ones. This is the phenomenon of time preference.1

Every actor requires some amount of time to attain his goal, and since man must always consume something and cannot entirely stop consuming while he is alive, time is always scarce. Thus, ceteris paribus, present or earlier goods are, and must invariably be, valued more highly than future or later ones. In fact, if man were not constrained by time preference and if the only constraint operating on him were that of preferring more over less, he would invariably choose those production processes which yielded the largest output per input, regardless of the length of time needed for these methods to bear fruit. He would always save and never consume. For instance, instead of making a fishing net first, Crusoe would have begun constructing a fishing trawler—as it is the economically most efficient method of catching fish. That no one, including Crusoe, can act in this way makes it evident that man cannot but “value fractions of time of the same length in a different way according as they are nearer or remoter from the instant of the actor’s decision.” “What restricts the amount of saving and investment is time preference.”2

Constrained by time preference, man will only exchange a present good for a future one if he anticipates thereby increasing his amount of future goods. The rate of time preference, which is (and can be) different from person to person and from one point in time to the next, but which can never be anything but positive for everyone, simultaneously determines the height of the premium which present goods command over future ones as well as the amount of savings and investment. The market rate of interest is the aggregate sum of all individual time-preference rates reflecting the social rate of time preference and equilibrating social savings (i.e., the supply of present goods offered for exchange against future goods) and social investment (i.e., the demand for present goods thought capable of yielding future returns).

No supply of loanable funds can exist without previous savings, i.e., without abstaining from a possible consumption of present goods (an excess of current production over current consumption). And no demand for loanable funds would exist if no one perceived an opportunity to employ present goods productively, i.e., to invest them so as to produce a future output that would exceed current input. Indeed, if all present goods were consumed and none invested in time-consuming production methods, the interest rate would be infinitely high, which, anywhere outside of the Garden of Eden, would be tantamount to leading a mere animal existence, i.e., eking out a primitive subsistence living by encountering reality with nothing but one’s bare hands and a desire for instant gratification.

A supply of and a demand for loanable funds only arise—and this is the human condition—if it is recognized first that indirect (more roundabout, lengthier) production processes yield a larger or better output per input than direct and short ones.3 Second, it must be possible, by means of savings, to accumulate the amount of present (consumption) goods needed to provide for all those wants whose satisfaction during the prolonged waiting time is deemed more urgent than the increment in future well-being expected from the adoption of a more time-consuming production process.

So long as these conditions are fulfilled, capital formation and accumulation will set in and continue. Land and labor (the originary factors of production), instead of being supported by and engaged in instantaneously gratifying production processes, are supported by an excess of production over consumption and employed in the production of capital goods. Capital goods have no value except as intermediate products in the process of turning out final (consumer) goods later, and insofar as the production of final products is more productive with than without them, or, what amounts to the same thing, insofar as he who possesses and can produce with the aid of capital goods is nearer in time to the completion of his ultimate goal than he who must do without them. The excess in value (price) of a capital good over the sum expended on the complementary originary factors required for its production is due to this time difference and the universal fact of time preference. It is the price paid for buying time, for moving closer to the completion of one’s ultimate goal rather than having to start at the very beginning. For the same reason, the value of the final output must exceed the sum spent on its factors of production (the price paid for the capital good and all complementary labor services).

The lower the time-preference rate, the earlier the onset of the process of capital formation, and the faster the roundabout structure of production will be lengthened. Any increase in the accumulation of capital goods and the roundaboutness of the production structure in turn raises the marginal productivity of labor. This leads to either increased employment or wage rates, or even if the labor supply curve should become backward sloping with increased wage rates, to a higher wage total. Supplied with an increased amount of capital goods, a better paid population of wage earners will produce an overall increased—future—social product, thus also raising the real incomes of the owners of capital and land.

FACTORS INFLUENCING TIME PREFERENCE AND THE PROCESS OF CIVILIZATION

Among the factors influencing time preference one can distinguish between external, biological, personal, and social or institutional ones.

External factors are events in an actor’s physical environment whose outcome he can neither directly nor indirectly control. Such events affect time preference only if and insofar as they are expected. They can be of two kinds. If a positive event such as manna falling from heaven is expected to happen at some future date, the marginal utility of future goods will fall relative to that of present ones. The time-preference rate will rise and consumption will be stimulated. Once the expected event has occurred and the larger supply of future goods has become a larger supply of present goods, the reverse will happen. The time-preference rate will fall, and savings will increase.

On the other hand, if a negative event such as a flood is expected, the marginal utility of future goods rises. The time-preference rate will fall and savings will increase. After the event, with a reduced supply of present goods, the time-preference rate will rise.4

Biological processes are technically within an actor’s reach, but for all practical purposes and in the foreseeable future they too must be regarded as a given by an actor, similar to external events.

It is a given that man is born as a child, that he grows up to be an adult, that he is capable of procreation during part of his life, and that he ages and dies. These biological facts have a direct bearing on time preference. Because of biological constraints on their cognitive development, children have an extremely high time-preference rate. They do not possess a clear concept of a personal life expectancy extending over a lengthy period of time, and they lack full comprehension of production as a mode of indirect consumption. Accordingly, present goods and immediate gratification are highly preferred to future goods and delayed gratification. Savings–investment activities are rare, and the periods of production and provision seldom extend beyond the most immediate future. Children live from day to day and from one immediate gratification to the next.5

In the course of becoming an adult, an actor’s initially extremely high time-preference rate tends to fall. With the recognition of one’s life expectancy and the potentialities of production as a means of indirect consumption, the marginal utility of future goods rises. Saving and investment are stimulated, and the periods of production and provision are lengthened.

Finally, becoming old and approaching the end of one’s life, one’s time-preference rate tends to rise. The marginal utility of future goods falls because there is less of a future left. Savings and investments will decrease, and consumption—including the nonreplacement of capital and durable consumer goods—will increase. This old-age effect may be counteracted and suspended, however. Owing to the biological fact of procreation, an actor may extend his period of provision beyond the duration of his own life. If and insofar as this is the case, his time-preference rate can remain at its adult-level until his death.

Within the constraints imposed by external and biological factors, an actor sets his time-preference rate in accordance with his subjective evaluations. How high or low this rate is and what changes it will undergo in the course of his lifetime depend on personal psychological factors. One man may not care about anything but the present and the most immediate future. Like a child, he may only be interested in instant or minimally delayed gratification. In accordance with his high time preference, he may want to be a vagabond, a drifter, a drunkard, a junkie, a daydreamer, or simply a happy-go-lucky kind of guy who likes to work as little as possible in order to enjoy each and every day to the fullest. Another man may worry about his and his offspring’s future constantly and, by means of savings, may want to build up a steadily growing stock of capital and durable consumer goods in order to provide for an increasingly larger supply of future goods and an ever longer period of provision. A third person may feel a degree of time preference somewhere in between these extremes, or he may feel different degrees at different times and therefore choose still another lifestyle-career.6

However, no matter what a person’s original time-preference rate or what the original distribution of such rates within a given population, once it is low enough to allow for any savings and capital or durable consumer-goods formation at all, a tendency toward a fall in the rate of time preference is set in motion, accompanied by a “process of civilization.”7

The saver exchanges present (consumer) goods for future (capital) goods with the expectation that these will help produce a larger supply of present goods in the future. If he expected otherwise he would not save. If these expectations prove correct, and if everything else remains the same, the marginal utility of present goods relative to that of future ones will fall. His time-preference rate will be lower. He will save and invest more than in the past, and his future income will be still higher, leading to yet another reduction in his time-preference rate. Step by step, the time-preference rate approaches zero—without ever reaching it. In a monetary economy, as a result of his surrender of present money, a saver expects to receive a higher real-money income later. With a higher income, the marginal utility of present money falls relative to future money, the savings proportion rises, and future monetary income will be even higher.

Moreover, in an exchange economy, the saver–investor also contributes to a lowering of the time-preference rate of nonsavers. With the accumulation of capital goods, the relative scarcity of labor services increases, and wage rates, ceteris paribus, will rise. Higher wage rates imply a rising supply of present goods for previous nonsavers. Thus, even those individuals who were previously nonsavers will see their personal time-preference rates fall.

In addition, as an indirect result of the increased real incomes brought about through savings, nutrition and health care improve, and life expectancy tends to rise. In a development similar to the transformation from childhood to adulthood, with a higher life expectancy more distant goals are added to an individual’s present value scale. The marginal utility of future goods relative to that of present ones increases, and the time-preference rate declines further.8

Simultaneously, the saver–investor initiates a “process of civilization.” In generating a tendency toward a fall in the rate of time preference, he—and everyone directly or indirectly connected to him through a network of exchanges—matures from childhood to adulthood and from barbarism to civilization.

In building up an expanding structure of capital and durable consumer goods, the saver–investor also steadily expands the range and horizon of his plans. The number of variables under his control and taken into account in his present actions increases. Accordingly, this increases the number and time horizons of his predictions concerning future events. Hence, the saver–investor is interested in acquiring and steadily improving upon his knowledge concerning an increasing number of variables and their interrelationships. Yet once he has acquired or improved his own knowledge and verbalized or displayed it in action, such knowledge becomes a “free good,” available for imitation and utilization by others for their own purposes. Thus, by virtue of the saver’s saving, even the most present-oriented person will be gradually transformed from a barbarian to a civilized man. His life ceases to be short, brutish, and nasty, and becomes longer, increasingly refined, and comfortable.

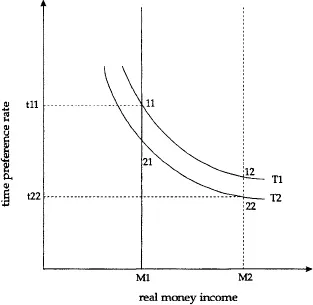

Figure 1 provides a graphic illustration of the phenomena of time preference and the process of civilization. It relates individual time-preference rates (the height of the premium of a specified present good over the same good at a specified later date which induces a given individual to engage in intertemporal exchange) on the vertical axis to the individual’s real money income (his supply of present money) on the horizontal. In accordance with the law of marginal utility, each individual time-preference curve, such as T1 or T2, slopes downward as the supply of present money increases. The process of civilization is depicted by a movement from point 11—with a time preference rate of til—to point 22—with a time preference rate of t22. This movement is the composite result of two interrelated changes. On the one hand, it involves a movement along T1 from point 11 to 12, representing the fall in the time-preference rate that results if an individual with a given personality possesses a larger supply of present goods. On the other hand, there is a movement from point 12 to 22. This change from a higher to a lower time-preference curve—with real income assumed to be given—represents the changes in personality as they occur during the transition from childhood to adulthood, in the course of rising life-expectancies, or as the result of an advancement of knowledge.

Figure 1

Time Preferences and the Process of Civilization

TIME PREFERENCE, PROPERTY, CRIME, AND GOVERNMENT

The actual amount o...