![]() PART I

PART I![]()

Chapter 1

The Art of Noises

Let’s walk together through a great modern capital, with the ear more attentive than the eye, and we will vary the pleasures of our sensibilities by distinguishing among the gurglings of water, air and gas inside metallic pipes, the rumblings and rattlings of engines breathing with obvious animal spirits, the rising and falling of pistons, the stridency of mechanical saws, the loud jumping of trolleys on their rails, the snapping of whips, the whipping of flags. We will have fun imagining our orchestration of department stores’ sliding doors, the hubbub of the crowds, the different roars of railroad stations, iron foundries, textile mills, printing houses, power plants and subways.1

Luigi Russolo

Machine Aesthetics and Enharmonic Intervals

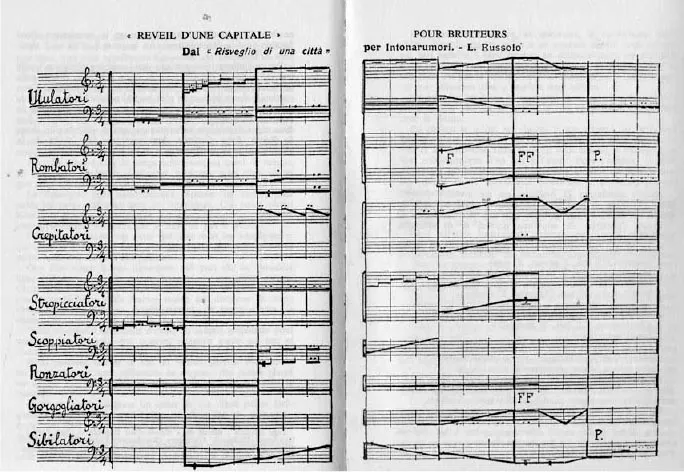

Having been published by Lacerba, a renown Florentine futurist journal, we know seven bars of Awakening of a Capital, composed in 1913 by Luigi Russolo.2 The score features 12 pentagrams for curious instruments named noise intoners, representing pitch, duration and the loudness of the sounds to play.

There are two staves for each group of howling, roaring, crackling and screeching instruments, and one staff for each group of rumbling, rustling, gurgling and hissing instruments. Listening to this passage we recognize typically urban noises, mostly engines and gears belonging to the cars and trams that were beginning to appear in towns at the beginning of the century. It is, to all effects, a symphonic poem that describes the metropolis, a favourite subject for futurists.

The avant-garde futurist movement aimed to create a new genre of musical expression by exploiting new tonalities, new harmonies, new melodies and new instruments. Following the ideals manifested in the corresponding literary and visual arts movements, the aspiration of futurist musicians is to represent the dynamics of modernity, glorifying scientific and technical innovation and promoting the aesthetics of the machine. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s statement, declared in the first futurist manifesto, published on February 20, 1909, by Le Figaro, is well-known:

Figure 1.1 Luigi Russolo, Awakening of a Capital

Source: Luigi Russolo 1975, pp. 90–91. Used by permission of Editions l’Age d’Homme..

We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath—a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.3

The first manifesto of futurist musicians, by Francesco Balilla Pratella, is dated October 11, 1910.4 This manifesto refers to Marinetti’s intents, to his strong, fearless and audacious approach, and to the opinion that museums, libraries and academies were cemeteries and that admiring and emulating the past was useless. It is presented as a call to arms for young people against the Italian musical world of the time. Opera is considered vulgar and critics mediocre. With the intent of freeing musical sensibilities from the imitation of the past, Pratella looks for inspiration in natural phenomena.

The need for a new musical language finds an ideal solution in evading even temperament.5 With the aim of enriching the palette of musical sounds, their timbres and their nuances, the semitone’s status as the indivisible, fundamental unit of the tonal system is contested. Since nature has created an infinite gradation of sounds, it should be possible to make music using the entire acoustic spectrum, including enharmonic intervals.6

On March 11, 1911, Pratella published the technical manifesto of futurist music,7 insisting on the necessity of moving on beyond predetermined tonal and modal scales, through enharmonic intervals.

A few years before, Ferruccio Busoni had already written about enharmonic intervals and the necessary evolution of the Western Musical system. In the Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music (1906),8 Busoni wrote about experiments concerning third-tones and divided the octave into 36 intervals, with two series of third-tones placed at a distance of a semi-tone,9 in the hope of going beyond the restrictions imposed by traditional musical instruments. The modern composer must be able to make music with an unlimited gradation of sounds.

In his essay about a new aesthetic of music, Busoni expressed interest in an instrument invented by Thaddeus Cahill to transform electric current into vibrations, so as to produce sounds by regulating the number of oscillations, allowing him total control over the pitch of sounds.10

Introducing micro-intervals into Western Music meant an enrichment of compositional means and a broadening of the aural sphere. Noises started to become elements of interest for composers.

Families of Noises

If Busoni, precursor and predictor, had commenced a musical exploration beyond the canonic categories of musical notes, the Futurists, who were looking for novel acoustical sensations, found new sounds in industrial yards and means of transportation (trains, trams, airplanes, cars, etc.).

The protagonist of this upheaval was Luigi Russolo. A Futurist painter since 1910, he soon interrupted his painting activity and dedicated himself to musical experimentation. He was the first to theorize the use of noise-sound in music. In 1913, following the turbulent Futurist performances at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome on February 21 and March 9, Russolo wrote a letter-manifesto entitled The Art of Noises, addressed to Balilla Pratella.

He presented a brief history of Western Music, interpreting the use of noise as a logical consequence in composition that was coherent with the renewed sensibility of modernity. When life had been lived in silence, music had sought purity and gentleness. The advent of machines had now made it natural to look for dissonant and rough sound combinations, thus coming closer to noise-sound.

For years, Beethoven and Wagner have deliciously shaken our hearts. Now we are fed up with them. This is why we get infinitely more pleasure imagining combinations of the sounds of trolleys, autos and other vehicles, and loud crowds, than listening once more, for instance, to the heroic or pastoral symphonies. It is hardly possible to consider the enormous mobilization of energy that a modern orchestra represents without concluding that the acoustic results are pitiful. Is there anything more ridiculous in the world than 20 men slaving to increase the plaintive meowing of violins?11

The need to recognize the sonic qualities of noise was presented as the inevitable result of musical evolution. The introduction of noise into music was necessary because traditional theories were no longer sufficient to express modern sensibility. Russolo was referring to natural and artificial noises, such as thunders roaring, winds hissing, waterfalls pelting down, streams gurgling, leaves rustling and horses trotting, together with trams and cars, engines accelerating and iron rims running on the pavement.

For an in-depth analysis of noises, Russolo decided to classify them. He claimed that every noise had a predominant tone and rhythm, and, more or less present, secondary tones and rhythms. His classification presents six families of noise-sounds: 1) roars, thunderings, explosions, hissing roars, bangs, booms; 2) whistling, hissing, puffing; 3) whispers, murmurs, mumbling, muttering, gurgling; 4) screeching, creaking, rustling, humming, crackling, rubbing; 5) noises obtained by beating on metals, woods, skins, stones, pottery, etc.; 6) voices of animals and people, shouts, screams, shrieks, wails, hoots, howls, death rattles, sobs. The main noises of everyday life fell into one of these six categories, or could be identified using combinations of the primary noises.

The idea of identifying noises and classifying them into families introduced an interesting principle, which was to be developed by, among others, Pierre Schaeffer in his theorization of typological and morphological sound systems. This approach seems pertinent to present-day research in soundscapes and to policies regarding noise: rather than considering noises as indistinct entities, it is preferable to develop qualitative criteria proposing specific practices for each noise.

Noise Intoners

Analyzing noises, classifying them into categories and considering them as complex sounds (equivalent to the sum of pure sounds), are interesting procedures when trying to abstract the characters of sounds and reproduce them. Russolo was in search of the mechanical principles that generate noise. He wanted to assemble a futurist orchestra able to produce all possible timbres. His aim was to construct instruments able to voice the characters of each family of noises and modulate the secondary components of a specific noise, regulating tone and rhythm details with special devices.

After presenting the Manifesto, Russolo started the construction of noise-intoning instruments with the help of his brother Antonio and his friend Ugo Piatti, in their laboratory in via Stoppani, Milan. They built a series of large wooden colored boxes of various dimensions, played by means of handles, to be triggered by the musician’s right hand or by battery-switches, with an electric current of four or five volts. A lever with pointers, regulated by the left hand of the performer, showed the graduated scales of tones, semitones and fractions of tones that could be obtained, determining the pitch of the predominant tone. The more or less rapid movement of the handle controlled the volume of the sound. Variations in intensity could transform one noise into another one of the same family. Metal plates, gears and various objects were placed inside the noise intoners and vibrated when the instrument was played. Each noise intoner could be soprano, alto, tenor or bass.

The first noise intoner was presented in Modena on June 2, 1913, at Teatro Storchi. A demonstration performance with 15 instruments followed, on August 11, in Marinetti’s apartment in Milan, and then in London and in other European cities.

On April 21, 1914, Russolo conducted at the Teatro Dal Verme in Milan the Futurist Noise Intoners Grand Concert. The program presented three noise spirals: Awakening of Capital, Luncheon on the Kursaal Terrace and Meeting of Automobiles and Airplanes. The orchestra was composed of 18 noise intoners. The audience reacted violently, interpreting the concert as a provocation, and the authorities were forced to intervene.

On June 17, 20 and 24, 1921, Antonio Russolo conducted at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées in Paris three concerts for noise intoners and orchestra. The program presented four pieces by Antonio Russolo and two by Nuccio Fiorda. Twenty-seven noise intoners were used. The success of the first concert was restrained by the confusion created by André Breton and other Dadaists. Also Manuel de Falla, Maurice Ravel, Igor Stravinsky, Arthur Honegger, Alfredo Casella, Gustav Kahn and Paul Claudel attended the concert. The noise intoners were appreciated by the critics and by personalities such us Sergei Prokofiev, Sergei Diaghilev and Léonide Massine. In an article published by De Stijl, Piet Mondrian commented the concert, finding in noise intoners the first step towards an important reform of artistic means of expression.12

Although noise intoners were designed to reproduce urban noises, the compositional ideals of Futurist musicians were to avoid a simple imitation of everyday life. The aim was rather to stylize the sonic material, to liberate it from its original sense and sound source so as to obtain a new aural sphere. The art of noises was contrary to the reproduction of reality as had occurred in Late Romanticism. Noise-sound was used as a Duchamp ready-made: everyday noises were extrapolated from their original environment and considered as independent elements.

If in the beginning a descriptive intent was predominant, as in Awakening of a Capital, soon the intent was to mix the sound qualities of noises. The aim was to dominate noises, to organize them by removing their accidental character and abstracting them from the causes that produced them, controlling tone, rhythm, loudness and timbre as desired. Strictly musical principles were applied to noises. Urban noises entered concert halls.