![]()

Chapter 1

Provincial Cosmopolitanism: An Introduction

Göran Rydén

A Cosmopolitan Library – A Point of Departure

In 1739, Charles De Geer arrived at Leufsta bruk, Sweden’s largest ironworks, some 100 kilometres north of Stockholm, as its new owner. Iron making in Sweden was organised in bruks, which were a kind of combination of an industrial community where the iron production took place in furnaces and forges, and a large landed estate, supplying charcoal and other resources from the land. Access to mines was sometimes included. Charles De Geer had inherited Leufsta bruk nine years earlier from an uncle bearing the same name, but at that time the new heir still lived with his parents on an estate outside Utrecht in the Netherlands; Charles was just 10 years old when he came into possession of Leufsta, and he remained in Holland until his father’s death in 1738. Although Charles De Geer was brought up in Holland he had been born in Sweden, and though he bore a Dutch name his family had been present in Sweden for about a century. His great grandfather was Louis De Geer, who had arrived in Sweden as a wealthy merchant from Amsterdam, although initially from Wallonia, and came to have a large impact on Swedish economic performance in general, but more specifically on its iron industry. Louis De Geer soon came into the possession of Leufsta bruk, as well as other large iron-making estates in the county of Uppland, and it remained in the family’s hands until very recently. Owning Leufsta also meant control of the Dannemora mine, one of the richest deposits of iron ore in Europe.1

It was thus a cosmopolitan young man who arrived at Leufsta in 1739; he belonged to a dynasty of merchants who recognised no borders and he had already, by 19 years of age, crossed many boundaries, linguistic and others. He made notes in his personal account book in Dutch, but soon began to write letters in Swedish, and was to compose scientific books about insects in French. Charles De Geer brought this cosmopolitanism with him to Leufsta, which developed during his long reign into a kind of ‘micro’ cosmopolitan society. A century before, Louis De Geer had brought skilled workers from his native Wallonia with him, as well as both Dutch capital and new technologies for both furnaces and forges. The younger De Geer built on that foundation, establishing the iron from Leufsta as a top brand on the European iron market, but he also added a European cultural touch to his community. Charles De Geer was quick to introduce novelties from Europe, and in the late 1750s he approached the young architect Jean Eric Rehn, who was to have a leading role in introducing rococo to Sweden, when he returned from a long journey in Italy and France. He was to refurbish the grand manor house and other buildings at Leufsta. However, culture was more than architecture to the new heir at Leufsta.

When Charles De Geer returned to the country of his birth, the bruk was run by his older brother as guardian, and a Directeur at the site. The latter, Eric Touscher, had prepared for the arrival of his new superior by penning a very ambitious guide for a future ironmaster, En liten handbok angående Leufsta Bruk &c. Wälborne Herren Herr Carl de Geer, wid ankomsten i Orten af En Des Tienare, öfwerlemnat 1739, bound into a small leather-covered book. In this ‘small handbook’, Touscher touched upon most aspects of being the manager of a large industrial enterprise operating in a global market; he began by dealing with the personnel, moving to matters of transport, technology and workshops before treating the more business-related matters. Touscher ended his manuscript with a small chapter called ‘Some necessary and well-meant reminders’. Whether De Geer heeded Touscher’s advice is not clear, but he turned out to be a very successful ironmaster, and died as a very rich man in 1778.2

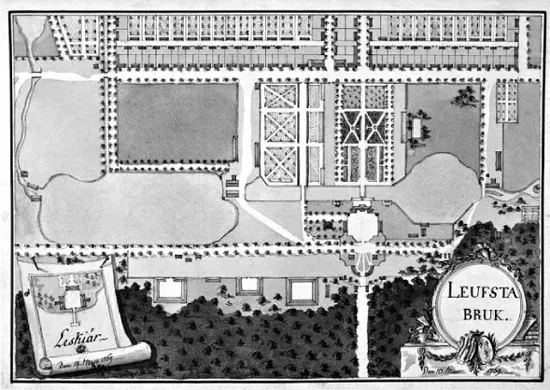

However, Touscher’s ‘well-meant reminders’ did not stop with matters related to being an ironmaster. He had also prepared a second handwritten leather-covered volume for his master, related to cultural aspects of being a gentleman of the time: ‘Catalogue over Charles De Geer’s collections at Leufsta’.3 Touscher had, at his own expense, collected coins and medals for his master; he had also bought books, as well as scientific instruments, guns and machines. All these items were catalogued, and they were stored in cupboards, drawers and rooms. The idea behind all this was to prepare De Geer for a social life as an owner of a large and well-reputed Swedish bruk; being a collector was an important part of that. If Touscher wanted to implant the art of collecting in the mind of his new young master he definitely succeeded, and Charles De Geer can in many ways be seen as a personification of eighteenth-century collecting. The armoury, the library and the cupboards that Touscher presented along with his little book really expanded with the new owner, becoming redecorated wings of his manor house, and in the hands of Jean Eric Rehn De Geer got a fashionable and purpose-built natural history cabinet (a room for displaying a collection) as well as a library.

That the natural history cabinet came to include a large collection of minerals is hardly strange, bearing in mind that De Geer generated his wealth from the mineral kingdom, and that a knowledge of different kinds of ore ought to have been within the bounds of his ‘useful knowledge’. However, the new master of Leufsta bruk has been more remembered by posterity for the other collection in the same cabinet: the assembly of insects in boxes ordered, more or less, according to the ‘systema naturae’ established by his fellow countryman, Linnaeus. De Geer became a naturalist of almost the same prominence as the great professor from Uppsala, but his Memoires pour server a L’Histoire des Insectes, published in seven volumes from 1752 to 1778, actually bears the same title as a work by another famous naturalist, the French René Antoine de Réamur.4

The southern wing of the house, situated alongside the lower works pond, was mirrored on the northern side of the house with an equally well-designed building, but this did not include any natural specimens, being filled instead with printed materials; this was Charles De Geer’s treasured library. On its purpose-built shelves he stored music sheets purchased from Amsterdam and the most recent engravings from Paris. De Geer was an accomplished harpsichordist and, with manuscripts sent to him, he could, together with family and friends, perform the music in vogue in Europe at the time; his collection included music by Händel and Vivaldi, but also by less well-known masters such as Schaffrath, Pepusch and Tartini.5 The master of Leufsta could with equal ease keep abreast of what was going on in the art scene of the French capital, with engravings sent to him – his collection included works by masters such as Watteau and Boucher.6 The collection of books, however, dwarfed the assembled music sheets and engravings, and was at least as cosmopolitan! There were books in Swedish, especially related to the iron industry, but De Geer had almost a full collection of works from the French Enlightenment, with authors like Voltaire, Montesquieu and Rousseau to the fore, and the shelves were equally filled with books by naturalists such as Réamur and Buffon. Last but not least, the Leufsta master possessed the most important work of them all, the Encyclopédie, published under the editorship of d’Alembert and Diderot.7

Leufsta was Sweden’s largest and most prominent bruk, but it was a community challenging what could be said to be Swedish. For a start, it was a community largely inhabited by descendants of skilled workers who had migrated from the Netherlands in the seventeenth century, still working the iron in furnaces and forges according to technology brought from their native Wallonia. It was also a community that, from an architectural perspective, bore a significant resemblance to developments in the rest of Europe, but foremost it was a community totally in the hands of the De Geer family. The new owner, Charles De Geer, invigorated the ties to the Dutch economy, as well as establishing iron from Leufsta in the top tier of the European iron market. The profits from dealings in this market enabled De Geer to live his cosmopolitan life in his redecorated manor house, with his natural history cabinet and his library. In a symbolic way, we can imagine the Leufsta master entering his library and taking a volume of the Encyclopédie from his shelves. If he had chosen the fourth volume, with plates, from 1765, he could have viewed the plan and drawings of a French forge which was adopted for the Walloon method.8 Had he raised his head from the book and looked out of the window, he could have seen one of his own forges using the same technology. Leufsta was an iron-making bruk in Sweden, but it was also an unmistakably cosmopolitan place, crossing all kinds of boundaries. As a bruk, Leufsta was a ‘material’ space, sending out bar iron all over Europe, but it was also a ‘mental’ space, where Charles De Geer in his library could sit and imagine many different places scattered around the globe. As such it was a truly cosmopolitan place, situating Sweden within the material world as well as the mental world!

The eighteenth-century library at Leufsta bruk remains more or less intact. Its yellow plastered walls can still be seen in mirror image in the works pond, and its purpose-built shelves still contain the books Charles De Geer purchased from booksellers on the European continent. The building, the manor house, the natural history cabinet and some other houses are now owned by the Swedish state, while the books now belong to Uppsala University Library. It is open to the public, and shelf after shelf of Voltaire, Montesquieu, Buffon and Rousseau can still be viewed. We are not allowed to take the volumes from the shelves ourselves, but with help from guides or librarians we can view the drawings of a French forge in the Encyclopédie. Sadly, we cannot see the Leufsta forges any more, as they have been demolished, but Leufsta bruk is still one of the primary places to view the Swedish eighteenth century in all its cosmopolitan flair!

Figure 1.1 Leufsta bruk, 1769

Note: The Library is the small building to the right of the manor house, by the pond, and the natural history cabinet is the mirror image to the left.

Source: ‘Dagbok öfwer en resa igenom åtskillige av Rikets Landskaper …’ by Adolf Fredrik Barnekow and Emanuel De Geer. Courtesy of Uppsala University Library and Stora Wäsby gårdsarkiv.

The aim of this book is to view the Swedish eighteenth century from a cosmopolitan perspective, and there is hardly a better place to start such a venture than at Leufsta bruk, with its library. The place can be understood as one local community reaching out to a much wider global setting, with its bar iron being sold all around the Atlantic Ocean, as well as a place consuming commodities and culture from other (global) places, but its library can also be viewed as a kind of global microcosm; within its yellow plaster walls knowledge about the world was collected, and stored on shelves designed by Jean Eric Rehn. For eighteenth-century intellectuals, the Encyplopédie stood as a proxy for the ‘totality of knowledge’, and in order to fully understand the eighteenth century we must try to embrace such a way of thinking.9 Our (academic) world of today is far more divided and structured along different disciplinary, as well as political, boundaries. These have to be removed. This book began as a workshop held at the bruk, including a visit to the library, with Swedish eighteenth-century scholars from different disciplines; we came from history, economic history, the history of ideas, the history of religion, literature, musicology and art.

Our point of departure was to merge our different disciplinary backgrounds and in doing so create a more nuanced and elaborated picture of the Swedish cosmopolitan eighteenth century; the ambition was to strive for a picture more like the one imagined by the eighteenth-century intellectuals. The disciplinary differences were not, however, to be abandoned altogether, as each of us was asked to write a chapter based on prior themes and knowledge; we have remained attached to features close to our own disciplines. Instead, this more unified picture was to be found in the angles we adopted while writing our texts. We started from a spatial understanding of the Swedish eighteenth century, whereby Sweden is inserted in a wider global and cosmopolitan framework, and how such a setting might have influenced Sweden’s development. A second point of departure was found by swapping the spatial aspects for a more common beginning for historians, that of chronology; the eighteenth century has often been hailed as the beginning of our modern society, and such a standpoint is also common in Swedish historiography. Our approach has been to deal with the eighteenth century as a century of change and transition, but our analysis has also included a discussion of when this also became clear to people living in that century.

A last point in our common framework stems from our different disciplinary backgrounds. It is fair to say, picking two extremes, that economic history has a traditi...