eBook - ePub

The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement

Britannica Educational Publishing, William Hosch

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement

Britannica Educational Publishing, William Hosch

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Communication and, indeed, our comprehension of the world in general are largely ordered by the number and measurement systems that have arisen over time. This book delves into the history of mathematical reasoning and the progression of numerical thought around the world. With detailed biographies of seminal thinkers and theorists, readers develop a sophisticated understanding of some of the most fundamental arithmetical concepts as well as the individuals who established them.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement de Britannica Educational Publishing, William Hosch en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Matematica y Teoria dei numeri. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

MatematicaCategoría

Teoria dei numeriCHAPTER 1

NUMBERS

The notions of numbers and measurement appeared thousands of years ago. Early herders needed to know how many goats they had in their flocks. Early farmers needed to understand how much grain they had stored for the winter. When bartering, people needed to keep track of how many items or how much of a substance was traded. This volume presents the history and principles of these subjects.

Just as the first attempts at writing came long after the development of speech, so the first efforts at the graphical representation of numbers came long after people had learned how to count. Probably the earliest way of keeping record of a count was by some tally system involving physical objects such as pebbles or sticks. Judging by the habits of indigenous peoples today as well as by the oldest remaining traces of written or sculptured records, the earliest numerals were simple notches in a stick, scratches on a stone, marks on a piece of pottery, and the like. Having no fixed units of measure, no coins, no commerce beyond the rudest barter, no system of taxation, and no needs beyond those to sustain life, people had no necessity for written numerals until the beginning of what are called historical times. Vocal sounds were probably used to designate the number of objects in a small group long before there were separate symbols for the small numbers, and it seems likely that the sounds differed according to the kind of object being counted. The abstract notion of two, signified orally by a sound independent of any particular objects, probably appeared very late.

NUMERALS AND NUMERAL SYSTEMS

NUMBER BASES

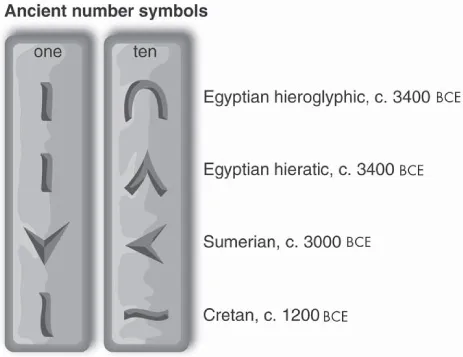

When it became necessary to count frequently to numbers larger than 10 or so, the numeration had to be systematized and simplified; this was commonly done through use of a group unit or base, just as might be done today counting 43 eggs as three dozen and seven. In fact, the earliest numerals of which there is a definite record were simple straight marks for the small numbers with some special form for 10. These symbols appeared in Egypt as early as 3400 BCE and in Mesopotamia as early as 3000 BCE, long preceding the first known inscriptions containing numerals in China (c. 1600 BCE), Crete (c. 1200 BCE), and India (c. 300 BCE). Some ancient symbols for 1 and 10 are given in the figure.

Some ancient symbols for 1 and 10. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The special position occupied by 10 stems from the number of human fingers, of course, and it is still evident in modern usage not only in the logical structure of the decimal number system but in the English names for the numbers. Thus, eleven comes from Old English endleofan, literally meaning “[ten and] one left [over],” and twelve from twelf, meaning “two left;” the endings -teen and -ty both refer to ten, and hundred comes originally from a pre-Greek term meaning “ten times [ten].”

It should not be inferred, however, that 10 is either the only possible base or the only one actually used. The pair system, in which the counting goes “one, two, two and one, two twos, two and two and one,” and so on, is found among the ethnologically oldest tribes of Australia, in many Papuan languages of the Torres Strait and the adjacent coast of New Guinea, among some African Pygmies, and in various South American tribes. The indigenous peoples of Tierra del Fuego and the South American continent use number systems with bases three and four. The quinary scale, or number system with base five, is very old, but in pure form it seems to be used at present only by speakers of Saraveca, a South American Arawakan language; elsewhere it is combined with the decimal or the vigesimal system, where the base is 20. Similarly, the pure base six scale seems to occur only sparsely in northwest Africa and is otherwise combined with the duodecimal, or base 12, system.

In the course of history, the decimal system finally overshadowed all others. Nevertheless, there are still many vestiges of other systems, chiefly in commercial and domestic units, where change always meets the resistance of tradition. Thus, 12 occurs as the number of inches in a foot, months in a year, ounces in a pound (troy weight or apothecaries’ weight), and twice 12 hours in a day, and both the dozen and the gross measure by twelves. In English the base 20 occurs chiefly in the score (“Four score and seven years ago …”); in French it survives in the word quatrevingts (“four twenties”), for 80; other traces are found in ancient Celtic, Gaelic, Danish, and Welsh. The base 60 still occurs in measurement of time and angles.

NUMERAL SYSTEMS

It appears that the primitive numerals were |, ||, |||, and so on, as found in Egypt and the Grecian lands, or −, =, ≡, and so on, as found in early records in East Asia, each going as far as the simple needs of people required. As life became more complicated, the need for group numbers became apparent, and it was only a small step from the simple system with names only for one and ten to the further naming of other special numbers. Sometimes this happened in a very unsystematic fashion; for example, the Yukaghirs of Siberia counted, “one, two, three, three and one, five, two threes, two threes and one, two fours, ten with one missing, ten.” Usually, however, a more regular system resulted, and most of these systems can be classified, at least roughly, according to the logical principles underlying them.

SIMPLE GROUPING SYSTEMS

In its pure form a simple grouping system is an assignment of special names to the small numbers, the base b, and its powers b2, b3, and so on, up to a power bk large enough to represent all numbers actually required in use. The intermediate numbers are then formed by addition, each symbol being repeated the required number of times, just as 23 is written XXIII in Roman numerals.

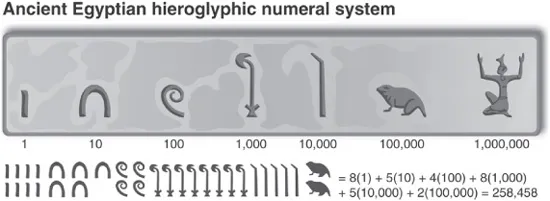

Ancient Egyptians customarily wrote from right to left. Because they did not have a positional system, they needed separate symbols for each power of 10. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The earliest example of this kind of system is the scheme encountered in hieroglyphs, which the Egyptians used for writing on stone. (Two later Egyptian systems, the hieratic and demotic, which were used for writing on clay or papyrus, will be considered below; they are not simple grouping systems.) The number 258,458 written in hieroglyphics appears in the figure.

Numbers of this size actually occur in extant records concerning royal estates and may have been commonplace in the logistics and engineering of the great pyramids.

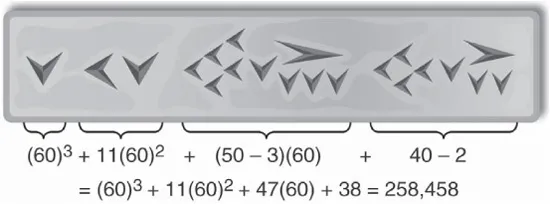

Cuneiform Numerals

Around Babylon, clay was abundant, and the people impressed their symbols in damp clay tablets before drying them in the sun or in a kiln, thus forming documents that were practically as permanent as stone. Because the pressure of the stylus gave a wedge-shaped symbol, the inscriptions are known as cuneiform, from the Latin cuneus (“wedge”) and forma (“shape”). The symbols could be made either with the pointed or the circular end (hence curvilinear writing) of the stylus, and for numbers up to 60 these symbols were used in the same way as the hieroglyphs, except that a subtractive symbol was also used. The figure shows the number 258,458 in cuneiform.

The number 258,458 expressed in the sexagesimal (base 60) system of the Babylonians and in cuneiform. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

The cuneiform and the curvilinear numerals occur together in some documents from about 3000 BCE. There seem to have been some conventions regarding their use: cuneiform was always used for the number of the year or the age of an animal, while wages already paid were written in curvilinear and wages due in cuneiform. For numbers larger than 60, the Babylonians used a mixed system, described below.

Greek Numerals

The Greeks had two important systems of numerals, besides the primitive plan of repeating single strokes, as in ||| ||| for six, and one of these was again a simple grouping system. Their predecessors in culture—the Babylonians, Egyptians, and Phoenicians—had generally repeated the units up to 9, with a special symbol for 10, and so on. The early Greeks also repeated the units to 9 and probably had various symbols for 10. In Crete, where the early civilization was so much influenced by those of Phoenicia and Egypt, the symbol for 10 was −, a circle was used for 100, and a rhombus for 1,000. Cyprus also used the horizontal bar for 10, but the precise forms are of less importance than the fact that the grouping by tens, with special symbols for certain powers of 10, was characteristic of the early number systems of the Middle East.

The Greeks, who entered the field much later and were influenced in their alphabet by the Phoenicians, based their first elaborate system chiefly on the initial letters of the numeral names. This was a natural thing for all early civilizations, since the custom of writing out the names for large numbers was at first quite general, and the use of an initial by way of abbreviation of a word is universal. The Greek system of abbreviations, known today as Attic numerals, appears in the records of the 5th century BCE but was probably used much earlier.

Roman Numerals

The direct influence of Rome for such a long period, the superiority of its numeral system over any other simple one that had been known in Europe before about the 10th century, and the compelling force of tradition explain the strong position that the system maintained for nearly 2,000 years in commerce, in scientific and theological literature, and in belles lettres. It had the great advantage that, for the mass of users, memorizing the values of only four letters was necessary—V, X, L, and C. Moreover, it was easier to see three in III than in 3 and to see nine in VIIII than in 9, and it was correspondingly easier to add numbers—the most basic arithmetic operation.

As in all such matters, the origin of these numerals is obscure, although the changes in their forms since the 3rd century BCE are well known. The theory of German historian Theodor Mommsen (1850) has had wide acceptance. Momson argued that the use of V for five is due to the fact that it is a kind of hieroglyph representing the open hand with its five fingers. Two of these V symbols, one inverted on the top of the other, would form an X, which eventually became the symbol for 10. Three of the other symbols, he asserted, were modifications of Greek letters not needed in the Etruscan and early Latin alphabet. These were X (chi) for 50, which later became the L; θ (theta) for 100, which later changed to C under the influence of the Latin word centum (“hundred”); and Φ (phi) for 1,000, which finally took the forms I and M. The last of these, the symbol M, was most likely chosen because the word mille means “a thousand.”

The oldest noteworthy inscription containing numerals representing very large numbers is on the Columna Rostrata, a monument erected in the Roman Forum to commemorate a victory in 260 BCE over Carthage during the First Punic War. In this column a symbol for 100,000, which was an early form of (((I))), was repeated 23 times, making 2,300,000. This illustrates not only the early Roman use of repeated symbols but also a custom that extended to modern times—that of using (I) for 1,000, ((I)) for 10,000, and (((I))) for 100,000, and ((((I)))) for 1,000,000. The symbol (I) for 1,000 frequently appears in various other forms, including the cursive ∞. All these symbols persisted until long after printing became common. In the Middle Ages a bar (known...

Índice

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Numbers

- Chapter 2: Great Arithmeticians and Number Theorists

- Chapter 3: Numerical Terms and Concepts

- Chapter 4: Measurements

- Chapter 5: Measurement Pioneers

- Chapter 6: Measurement Terms and Concepts

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Estilos de citas para The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement

APA 6 Citation

Educational, B. (2010). The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement ([edition unavailable]). Britannica Educational Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1639225/the-britannica-guide-to-numbers-and-measurement-pdf (Original work published 2010)

Chicago Citation

Educational, Britannica. (2010) 2010. The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement. [Edition unavailable]. Britannica Educational Publishing. https://www.perlego.com/book/1639225/the-britannica-guide-to-numbers-and-measurement-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Educational, B. (2010) The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement. [edition unavailable]. Britannica Educational Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1639225/the-britannica-guide-to-numbers-and-measurement-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Educational, Britannica. The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement. [edition unavailable]. Britannica Educational Publishing, 2010. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.