eBook - ePub

Geopolitics (Routledge Library Editions: Political Geography)

Pat O'Sullivan

This is a test

- 150 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Geopolitics (Routledge Library Editions: Political Geography)

Pat O'Sullivan

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This book, originally published in 1986, shows the importance of geography in international power politics and shows how geopolitical thought influences policy-making and action. It considers the various elements within international power politics such as ideologies, territorial competition and spheres of influences, and shows how geographical considerations are crucial to each element. It considers the effects of distance on global power politics and explores how the geography of international communication and contact and the geography of economic and social patterns change over time and affect international power balances.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Geopolitics (Routledge Library Editions: Political Geography) un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Geopolitics (Routledge Library Editions: Political Geography) de Pat O'Sullivan en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Sciences physiques y Géographie. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1 CONFLICT, TERRITORY AND DISTANCE

Geography and Politics

The premiss of this book is that geography matters in the relations between states, be they friendly or hostile. The strength of sympathetic and influential ties between the governments of nations is as much a matter of geographic distance as of political and cultural distance. Certainly in tracing both the causes and courses of wars, distance and space count for a lot at the grand strategic level. More locally in time and space, the details of geography provide the immediate setting for deadly conflict and strongly affect the outcome of war.

Whether we like it or not, the crux of international politics is war. We punctuate history with the violent contests of powers. The immediate circumstance of these outbreaks of killing and destruction is most usually contested turf. Political authority is conceived of as extending over some portion of the earth’s surface and the competition of those with power is over whose writ runs where. The domains of significance obviously extend beyond the limits of the nation state and the most serious conflicts today, from the viewpoint of man’s survival, arise in the ill-defined setting of the spheres of influence of the superpowers.

Even if we account importance in the more mundane terms of the use of our resources, we spend a lot of time, effort and material in fighting each other or getting ready to do so. The number of people whose lives are dedicated to war, to making weapons and the exertions and ingenuity put to these ends, uses up a large share of the world’s wealth. In our political dealings with each other we frequently suspend the moral rules-we ordinarily live by and are willing to kill and maim other people and destroy their property, or to threaten these things, in order to enable our leaders to get their way. Violence has been a ready resort and the preparation for war is a major feature of most civilised societies. Old men prepare and induce young men to kill the enemy. In the past the enemy was usually other young men but now it includes women, children, the old and the earth itself. The main reason for going to war has been to command more territory, and this remains the chief source of conflict. The greatest danger to our lives and well-being does not arise from the abstract clash of ideologies, but from the collision of the forces of the great powers or their clients over some piece of land. Whether the self-justifying rhetoric which accompanies such clashes is ‘revolutionary’ or ‘democratic’, the occasion of conflict is the control of territory. The fundamental dimension of conflict between nations is geographical. Geopolitics is the study of the geography of relations between wielders of power, be they rulers of nations or of transnational bodies. The limiting state of these relations is war and, no matter how we may abhor its wastefulness, this has been the main means of resolving the competitive process. War provides the negative image of affairs between peoples, and thus delineates the extent of peaceful co-operation or competition in the world.

There are now over 4 million people from 45 of the world’s 164 nations involved in combat, with up to 5 million people killed in fighting over the last three years. There is a concentration of turmoil at the pivot of the continents where Africa and Eurasia meet and a wider scatter beyond in Africa, South Asia and Latin America. The mainsprings of these outbursts of bloodletting and fire are mostly local. They are sparked by the frictions of social, economic and political change and personal ambition and are not in essence elements in any worldwide plan for conquest and domination. At times these local conflicts have been exploited by the government of one powerful state to embarrass that of another power. Or politicians and officials have sought to cover up their own lack of foresight, their ineptitude or inability to control affairs in their client states, by claiming that the troubles were mischievously generated by their protagonists as part of their campaign of conquest. Spokesmen for the USSR have claimed that the American government is behind the Afghan mujahedin, while Jeane Kirkpatrick put the El Salvador guerrilla war in somewhat confused global context when she announced that ‘an eastern offensive on our southern borders’ was not tolerable to ‘the west’. Some holders of power and office may actually believe in the simple theories of global politics in which they couch their foreign policy pronouncements. Whether these anathemas hurled at the opposition arise from a heartfelt belief or are merely a face-saving device, they contort the big powers’ attitudes to others’ conflicts. These are treated not on the basis of judgement of local rights and wrongs, but as an outlet for ambition and competitive strutting.

Mental Maps

In reacting to tension and strife around the world, the foreign policy establishments of the great powers do seem to have generalised images of political geography in their minds. These images are occasionally articulated as powerful, allegorical maps. The lines of their divisions of the globe clearly transcend the frontiers of nation states. Maps of political geography delineating the world’s 164 countries are obviously missing something. For the politicians and functionaries of the great powers there are, at least, mental maps of ‘our’ and ‘their’ territory which supersede national boundaries, with an anyman’s land lying between them. It is evident that the lines of demarcation on these mental maps do not coincide as between the two main camps, and the overlap of claims brings the dangerous might of the continent-spanning powers too close to each other for everyone’s comfort.

The Economist 26 December, 1981 offered an analysis of ‘the East–West struggle’ illustrated by maps depicting two levels of either pro-Soviet or pro-American leaning and a fifth state of non-alignment or contested affinity. This article was a contribution to the debate about the proper preparations for war against the USSR by the USA and some Western European nations. In this debate the respective government objectives of East and West and their expectations about their rival’s global ambitions are voiced in a vague fashion.

More militant Western leaders of opinion condemn the Soviets for expansive, territorial aggression while crediting the US government with a defensive, altruistic attitude. The defence of ‘freedom’ and a foggy, enveloping notion of US ‘national interest’ are sufficient, however, to warrant intrusion, direct or indirect, into the provinces of the opposition or the undecided lands between. The image of spheres of influence around the rival poles of the USSR and USA continues to frame the rhetoric of this competition. Since 1950 economic and political reality has departed further and further from the picture of bipolar contention, even though nuclear confrontation has remained essentially duopolistic.

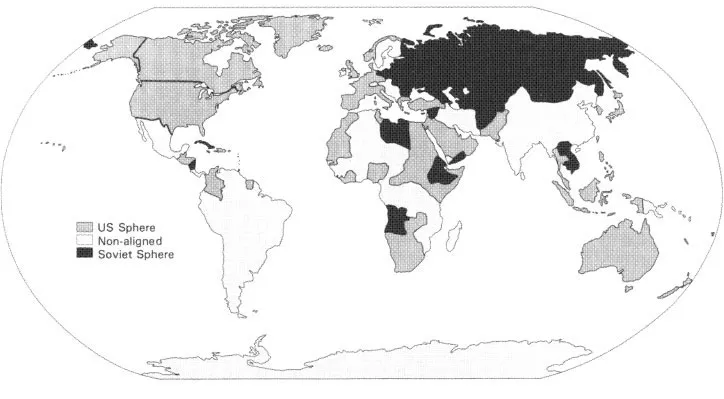

It is, of course, feasible to draw a map, such as Figure 1.1, of the domains over which the USA and USSR could be said to exert political leadership right now, reflecting the current of informed opinion and news, putting nations into one camp or the other, or leaving them unaligned. Such a bald statement of the two hegemonies would invite objection, exceptions and denials. Whether North Korea is inclined to Russia or China right now; whether Qadaffi is a creature of or embarrassment to the USSR; whether France’s premier is feeling Atlantic or European today; whether Soviet service will pay off in Iran or whether President Machel’s submission to South Africa signals a switch of camps for Mozambique — all are considerations open to dispute and will change the colours of the map from day to day. Such a map is a snapshot of Figure 1.1: Spheres of Influence an oscillating, evolutionary process subject occasionally to catastrophic change. Thus, it would have no lasting relevance. Yet it does seem from the words of statesmen and the imagery of their language that some mental construction of similar content and intent provides an ordering of their world and a matrix for the most important decisions made on the fate of mankind. Lines are drawn, spheres defined and encroachments contained on a projection of the globe, expressing politicians’ fears and designs. The scoreboard for the contest of their ambitions is a map.

Figure 1.1: Spheres of Influence

The three-toned simplicity of a map of the hegemonies is of little value other than to feed paranoia with a crude image of the political instant. To express the nuances and ambiguities of relations among nations with accuracy it would take many more than even the five shades of The Economist’s maps. The military dominance of the USA and USSR is beyond dispute, but the strength of their influence has been pushed and pulled back and forth in China, Southeast Asia and Latin America since 1950, while in the Middle East and Africa the two superpowers have probed and intertwined in tentative compensation for the European stand-off.

Geopolitics

What any mapping of the realms of power does suggest, however, is that the force of international influence does still reflect the tyranny of distance, despite the protestations of Wohlstetter and Bunge. The more removed a nation from either great power, the better the prospects of remaining neutral. A variety of theories can be invoked to explain why the magnitude of projected power should diminish with distance. The main purpose of this book is to explore this attenuation theoretically and empirically and its implications for international affairs. To signal this concern with matters of distance and place, I have used the title Geopolitics. This implies the use of geographical good sense in understanding or governing the relations between groups of people. If politics is the art of government, then the ‘geo’ prefix implies the application of geographical knowledge to this end. The term is usually applied to foreign policy, but clearly some domestic matters could benefit from the exercise of geographical nous.

The main service a geographer can provide in foreign affairs is to emphasise the defence which geography offers against the ambitions of rivals and to instil as much objective, geographical reality into the dealings between nations as possible. Distance, difficult terrain and the sea still provide obstinate barriers to fighting men and their machines. The space and surfaces between the urban cores and resource bases of the USA, USSR, Western Europe and China are big and awkward enough to afford them confidence that one will not attack the other directly with a view to conquest. The main dangers to peace, however, are seen to lie in the vulnerability of their clients and neighbours to indirect disruption. In dealing with these contingencies the strategies, ploys, doctrines and myths of rulers, functionaries and popular expressions of opinion frequently display departures between geographical reality and the mind maps which chart power and danger in foreign affairs. Fear and hate are fed by misperceptions and misapprehensions of geography.

The two main themes of this book, then, are the gaps between geographical myth and reality, and the persistent potency of distance in checking vaulting ambition.

Motives

To deal with these matters adequately we must first consider the motives of those who decide on and operate the relations between nations and their views of the world. This is the subject of Chapter 2. It has proved impossible to codify the motives of makers of foreign policy satisfactorily in order to produce a theory which will stand the usual tests of validity. Time after time events deny the assumption of simple utilitarian or altruistic objectives or, indeed, any singular rationale. There does, however, seem to be a persistent lust in some people to control the lives of others. Beneath the veneer of ethical and ideological rhetoric which has been used to justify actions, history records the results of individuals and groups giving rein to what appears to be an innate and widespread domineering impulse. Luther called this the animus dominandi, the lordly spirit. If it is not curbed by humility and self-discipline or checked by others, it can result in dominions that encompass great tracts of the earth. To generalise on the geographical arrangements of political life, it seems we must accept this aggressive spirit, which is widely accepted by the players in the international game themselves, as the fundamental driving force. From this viewpoint any failure to exploit a competitive advantage or another’s territorial withdrawal is interpreted as a ploy to regroup strength for future expansion or as a sign of weakness.

Perceptions

History also suggests that our rulers are as prone as the rest of us to misconstrue the nature of the world and the intentions of others. Many trains of events can only be traced to blundering stupidity and ignorance. The uncertainty which has plagued the dealings between the USA and USSR since the 1940s has arisen not only from the lack of correspondence between the official pronouncements and action of both sides, but also from the departures between the underlying objectives and actions — not only from duplicity, but also from errors of perception. Chapter 3 explores the variety of perceptions of this world.

To explore the perceptions which guide policy we begin with the variety of traditional and classical views of the world and the deep persistence of a sense of territoriality. The feeling of nationhood contrasts with a sense of belonging to broader groups such as Christendom or Islam. The visions and problems of imperialism and global hegemonies lead us into the geopolitics of Mahan, Mackinder and Haushofer.

To trace the origins of the views of the world which underlie today’s marking-out of spheres of influence, it is necessary to delve into the geopolitical context of Marxism; Lenin’s changing geographic perceptions; the synthesis of traditional Russian and ideological attitudes; Maoist rhetoric and age-honoured Chinese cosmology. As opposed to these visions, the overt imperialism of Britain and the Pax Britannica provided both a model and a target for the confusion of motives involved in the US rise to hegemony. The Monroe Doctrine, ‘democratic’ ideology and economic imperialism are some of the threads in an evolving pattern of American thought, speech and behaviour in foreign affairs. The ‘spheres’, ‘dominoes’, ‘arcs’ and ‘chains’ which crop up as images of political geography and the conflict with communism for influence over the world, have to be understood against this background. The ambivalence of the makers of policy over the Pax Americana and imperial responsibility is perhaps the most fascinating theme in international relations. While the USSR and China have reverted to traditional and comparatively static roles in recent years, there is a powerful body of opinion in the USA which advocates overturning the Russian polity. Foreign policy for these people is spoken of as a crusade to destroy communism and make the world safe for democracy. Containment, then, is a temporary expedient. In previous administrations the announced position was not so clearcut, teetering on the sharp edge formed by power and responsibility. This uncertainty as to the proper position to take has caused bewilderment and unease over the drawn-out and sometimes violent contest for de facto spheres of influence between the USA and USSR. Within the traditional alignments of US politics there is a fundamental division of geographical attention between the Pacific and Asia and the Atlantic and Europe. This dilemma reflects a tension between imperial and more co-operative tendencies. One mood of American politics was inclined to accelerate the retreat of European colonialism after 1945. Another humour tried to fill the political vacuum created by this withdrawal in an effort to contain communism. In the case of Indochina this culminated in a retreat of confused pain. Americans were shocked to discover a lack of correspondence between their perceptions of the state of the world and their role and the reality.

Theories

Chapter 4 looks at some theories of international competition and conflict. Making a theory involves describing phenomena and their interplay to understand how they behave, in the hope of predicting this behaviour. Thus, theory requires the representation of the things in question and the naming of the driving force which powers their movements. There are obviously different views on the motive force underlying global politics and a variety of ways of representing international relations with a view to explaining them. Of late there have been efforts to reconcile the classical realist view that the primary objective of foreign policy is security and power with the more recent welfare school of thought. The apparatus of economics has been adapted to international politics, defining the state as an organisation for the provision of protection and welfare in return for revenue. The people who constitute the state are seen as making corporate, hedonically rational decisions in their competition for resources and in their strategies. Such theorising could be made spatial by the introduction of distance and direction into its formulations. International politics could be viewed as an exercise in net benefit maximisation with determinable territorial equilibria, optimal scales of operation and desirable levels of commercial intercourse and military involvement. The dynamics of the international system could be treated as a matter of adjustments to technical change in communications, production and military capabilities. If location were incorporated as a variable in this framework, the theory could be rendered geographical by applying different costs of friction over land and sea, plain and mountain, grassland and forest. Terrain and channels of movement might be made explicit factors in the theory. But no matter how well and detailed the condition of the scenery could be laid out in theorising of this kind, its validity stands or falls on the grounds of the motives it ascribes to politicians. The evidence is that no generally acceptable conclusion is likely to be reached on this.

If we are willing to make a crassly simple assumption about the objectives of foreign policy, then it may be possible to produce a crude first approximation to geopolitical behaviour, in either deterministic or probabilistic fashion. The essence of the state is territoriality and the focus of international competition is control of territory. To simplify matters further to get a starting-point, geography can be reduced to a line. Competition for territory among a row of states along a line offers a first step. From this elementary beginning more elaborate representations might be built up.

In Chapter 4 we focus on two types of theory about t...

Índice

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- 1. Conflict, Territory and Distance

- 2. Motives and Decisions

- 3. Views of the World

- 4. Theories

- 5. Distance and Power

- 6. Measurement

- 7. Flows and Links

- 8. War and Peace

- Index

Estilos de citas para Geopolitics (Routledge Library Editions: Political Geography)

APA 6 Citation

O’Sullivan, P. (2014). Geopolitics (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1661955/geopolitics-pdf (Original work published 2014)

Chicago Citation

O’Sullivan, Pat. (2014) 2014. Geopolitics. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1661955/geopolitics-pdf.

Harvard Citation

O’Sullivan, P. (2014) Geopolitics. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1661955/geopolitics-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

O’Sullivan, Pat. Geopolitics. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2014. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.