![]()

1

Voice and Involvement at Work

Introduction

Paul J. Gollan, Bruce E. Kaufman, Daphne Taras, and Adrian Wilkinson

Competitive pressure on companies to boost productivity and performance has intensified in the last two or three decades due to a confluence of events, such as global integration of markets, a more finance-driven business environment, and industry deregulation and privatization. The ripple effects spread across all functional areas of business, affect all stakeholders, and can have positive or negative social consequences. Certainly employees and the human resource function are a case in point. Companies may react to greater competitive pressure by taking the low road through labour commodification, cost cutting, and worker disempowerment or the high road through investment in human capital, high-involvement work practices, and mutual-gain compensation.

This volume focuses on one particular component of human resource management and industrial relations practices—voice and involvement forums, committees and councils that represent employees in joint dealings with management outside of a union context. As a shorthand, we refer to these groups as non-union employee representation (NER). NER is a vivid case study of the two alternative paths companies can take in reaction to greater market competition. Proponents of NER, for example, advocate it as an important component of the high-road approach that builds more profitable organizations on employee empowerment and mutual gain. Critics, on the other hand, maintain that NER at best is ineffective in raising organizational performance and at worst is a component of the low-road approach, which increases profit by extending management control over labour and ridding the workplace of unions.

The idea and practice of giving employees opportunity for voice and involvement at the workplace has a long history, as does debate over its most appropriate form. Traditionally, the major institution for employee voice and involvement has been the independent labour union, often promoted as a way to achieve industrial democracy (Webb and Webb 1897) and constitutional government in industry (Commons 1905). However, the proportion of the workforce covered by unions has greatly diminished in most countries over the last three decades, opening or worsening what Freeman and Rogers (1999) call an employee participation–representation gap. For this reason, and also from concern about boosting workplace productivity and national economic performance, interest in business, academic, and policy-making circles in non-union voice options has expanded greatly over the last two decades.

Government labour departments have for many years measured union coverage, and the data provide a reasonably reliable picture of the extent of decline in union density and its variation across firms and industries. No similar data exist on NER density, however, so our knowledge of the extent of non-union voice options—including not only indirect forms of representational voice but also direct face-to-face types of voice—and their variation among firms and industries is much less certain (for suggestive evidence, see Lipset and Meltz 2000; Freeman, Boxall, and Haynes 2007; Willman, Gomez, and Bryson 2009; Godard and Frege 2013; and Dobbins and Dundon 2014). We do know, however, that relative to independent unions, NER gives considerably more emphasis to a collaborative and integrative “grow the pie” philosophy and set of Human Resources Management (HRM) practices rather than an adversarial and distributive “split the pie” approach (Kaufman and Taras 2000; Gollan 2007; Wilkinson, Donaghey, Dundon, and Freeman 2014). Hence, key terms used in the context of NER are not bargaining, contracts, shop stewards, and strikes but, instead, involvement, voice, participation, communication, team members, and mutual gain. Whether these terms describe a functioning reality or a rhetorical facade remains a much-contested issue, as does the issue of whether the union-avoidance term should also be included in this list.

The available evidence from various countries (reviewed in what follows) does suggest that NER has expanded, albeit unevenly due to differences in national legal regimes, business practices, and cultural attitudes. Also, survey evidence and case studies indicate that NER comes in a wide diversity of forms with different agendas, functions, and influence resources (Dundon and Gollan 2007; Taras and Kaufman 2006; Kaufman and Taras 2010). Academic research finds that NER does have two faces, one positive and one potentially negative. In some companies, with the right kind of NER and in favourable business circumstances, it has a positive effect on both organizational performance and employee welfare; other studies, however, find that NER is largely a marginal and mostly ineffective practice and, sometimes, is employed mainly to keep workers from organizing independent unions (Dobbins and Dundon 2014; Pyman 2014).

This volume sheds additional light on these matters through in-depth case studies of non-union representation councils and committees in twelve organizations across four countries. Statistical studies using national survey data are very useful for identifying general NER patterns and effects (e.g., Bryson, Charlwood, and Forth 2006). They are, however, relatively blunt instruments for investigating the process of NER, the strategies and motives of the parties, organizational factors that lead to NER success or failure, qualitative and subjective considerations and outcomes, and actionable implications for business and government decision makers. Believing these considerations are under-explored and also crucial to informed evaluation and successful practice of NER, we have opted for the case-study method. Of course, these case studies also reflect many features and influences to some degree unique to each organization, so generalizations have to be duly tempered.

We have selected case studies and authors with several innovative criteria in mind. First, we have sought to introduce a comparative cross-national element by selecting examples of NER from four Anglo-American countries. The countries are Australia, Canada, Great Britain, and the United States. These countries exhibit interesting variations in legal regimes, union density, collective bargaining arrangements, company HRM practices, and individualist/neoliberal versus collectivist/social democratic cultural-political orientations—all of which may have discernible effects on the form, function, and success of NER. However, we have restricted our set of countries to English heritage nations in order to maintain similarity in basic framework characteristics related to business, political, and social-cultural institutions and practices. One consequence is that we do not include European-style works councils in our ambit (see Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman 2010; Nieuhauser 2014).

A second innovative feature of the case studies is that they provide a longitudinal analysis of NER, sometimes extending over several decades. A criticism of NER is that the programs can have a short half-life, sometimes taking off with much management push and enthusiasm but then, after a few years, fading as the crisis goes away or a new management team takes over. Other NER plans, however, have lived and prospered for several decades and even nearly a century. So our chapter authors, as much as possible, go beyond the point-in-time snapshot in order to discover more about the life-cycle pattern of NER and the factors that lead to longevity versus fade-out.

A third feature of the case studies is that they span both for-profit and not-for-profit organizations. Nine of the case studies are private-sector companies, varying in size from a few hundred employees to more than 70,000 and across a range of industries and lines of business (e.g., banking, low-tech and hi-tech manufacturing, airline and rail transportation, and oil production and refining). Three of the case studies are public-sector organizations, including a national police force, a university, and a federal government.

Finally, we have chosen our authors to bring a mix of human resource management (HRM) and industrial relations (IR) perspectives to the case-study analyses. This combination gives adequate representation to the diverse purposes and perspectives surrounding NER, including organizations’ interests in higher productivity and profit and workers’ interests in improved terms and conditions of employment and a meaningful say at work. We also bring together HRM and IR in this volume in order to promote more cross-field collaboration and melding of viewpoints among our research colleagues. IR researchers have taken the lead in researching NER but do so more from a perspective of workforce governance and interest representation for workers (Ackers 2010). Many HRM researchers instead look at employee voice structures as a management communication-involvement tool evaluated primarily by their effect on organizational performance (Klaas, Olson-Buchanan, and Ward 2012). They also often gloss over the substantive difference between direct and indirect forms of participation, including the sometimes complicated legal status of NER (Morrison 2011). We seek to achieve a better melding of these diverse perspectives.

NER: An Overview of Forms and Functions

NER is an umbrella term for an unusually diverse set of forms and practices. Further, the nomenclature varies from country to country. In Canada, for example, a large-scale NER group may be called a Joint Industrial Council (JIC) or Employee-Management Advisory Committee (EMAC), while in the UK and Australia a popular term is Joint Consultative Committee (JCC). In the United States, labour law heavily restricts enterprise-level NER forms (discussed in what follows), and so it typically appears in small-scale form, such as an employee-involvement group, joint safety committee, or gain-sharing committee.

NER is one form of providing voice to employees, but there are also many others. Voice is defined in different ways in the academic literature. Wilkinson, Dundon, Marchington, and Ackers (2004) conclude from field interviews that managers associate workplace voice with “consultation,” “communication,” and “say.” They also find that managers tend to define workplace voice along two dimensions. The first is voice form (direct vs. indirect) and the second is voice agenda (shared vs. contested). In a follow-up article (Dundon, Wilkinson, Marchington, and Ackers 2004), they suggest these two dimensions need to be rounded out with a third. This dimension is voice influence and its close synonym, power.

Accordingly, the three principal dimensions of workplace voice can be specified as form, agenda, and influence. Each, in turn, varies along a continuum with endpoints defined by polarities. For example, the three voice dimensions may be represented as (with correlates):

- Direct versus indirect (individual, face-to-face vs. collective, representative)

- Shared versus contested (integrative, win-win vs. distributive, win-lose)

- Communication versus influence (suggestion, complaint vs. cost or benefit action)

These dimensions of voice yield a 2 × 2 × 2 matrix and eight permutations, which may be ordered from low to high in terms of organizational impact and employee influence. This idea is given parallel representation in a chapter by Wilkinson, Gollan, Marchington, and Lewin (2010) on conceptualizing employee participation. They show in diagrammatic form an “Escalator of Participation” (p. 11). It is a forward-sloped line with five steps going from low to high participation, based on degree, form, level, and range of subject matter.

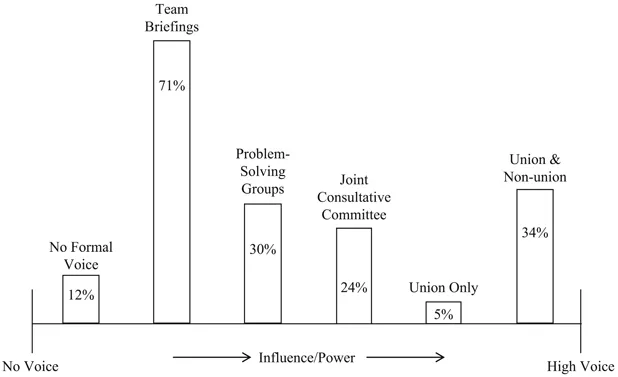

Figure 1.1 repackages their diagram into an “Escalator of Voice” or, alternatively, “Menu of Voice Options.” The figure shows that voice options in an organization vary along a continuum from low to high, as measured by an index of the three voice dimensions identified (form, agenda, and influence). For simplicity, the continuum of voice forms is presented along a straight line rather than an ascending eight-step function. At the low end are voice options where all three dimensions take a low value in terms of organizational impact. An example is the triplet Direct, Shared, and Communication, such as when an individual employee engages in cooperative discussion with a direct supervisor about a suggestion to improve customer service. At the high end are voice forms where the three dimensions collectively create the largest organizational impact. An example is Indirect, Contested, and Influence, such as a strong trade union that uses collective bargaining and strikes to gain higher wages for workers. Thus, at the left-hand side of the continuum are individual, informal, and communication types of voice, while moving rightward on the continuum leads to voice forms with increasingly collective, formal, and power attributes.

Figure 1.1 Voice Frequency Distribution, United Kingdom

Also shown in the diagram is a voice frequency distribution displayed above the continuum. It is a plot of data showing the percentage of British workplaces (twenty-five or more people) in 2004 with various voice forms. British data are used because they come from a nationally representative source (the 2004 Workplace Employment Relations Survey [WERS]), and the country’s legal system is one of the least restrictive regarding employer– employee choice among voice options (Freeman, Boxall, and Haynes 2007; Willman, Gomez, and Bryson 2009).

In this survey, only a small minority (12 percent) of workplaces are reported as No Voice—meaning absence of at least one formal voice mechanism (informal voice may well still be present). Of the 88 percent that have a voice mechanism, they sort into three broad categories—with a fourth small residual category, “Nature not reported” (2 percent): Nonunion Only (48 percent), Union and Nonunion (34 percent, or dual channel), and Union Only (4 percent). In Figure 1.1, the No Voice option is placed at the left-hand endpoint (least influence), the combined Union/Nonunion Voice option is placed at the right-hand endpoint (having the most forms of voice and thus presumptively most influence), and Nonunion Only and Union Only occupy positions to the left and right of the middle. Rather than show just the Nonunion Only category, it is modestly disaggregated to show three particular types of voice arrangements. They are Team Briefings (71 percent), Problem-Solving Groups (30 percent), and Joint Consultative Committees (24 percent). These three voice forms are selected from a longer list provided by WERS for the Nonunion Only category because they help draw out the visual/descriptive notion of a voice frequency distribution and also illustrate the voice escalator idea in terms of ascending from direct and mostly communication forms to indirect and greater influence forms. Note that the bars in the figure do not sum to 100 percent because the percentages for these three items are non-commensurate (within frequency for Nonunion Only).

The key point to grasp from Figure 1.1 is that the central domain of NER is in the relative middle of the overall voice continuum. NER is by definition an indirect form of voice and, thus, typically involves groups of employees organized to represent others. This places NER to the right of the low end of the continuum occupied by organizations having only a direct form of voice. Examples are voice provided solely on an individual face-to-face basis, such the traditional “open door” policy (subsumed in the No Voice category in Figure 1.1). Going one step up the escalator, another form of direct voice is a morning meeting between team members and their supervisor (Team Briefings in the diagram). On the other hand, NER does not extend all the way to the high end of the voice continuum because it ranks lower than trade unions and other forms of independent representation (e.g., professional associations) on the dimension of influence/power. A NER form, for example, is the JCC in Figure 1.1 which is an indirect form of voice—like a trade union—but which does not use formal bargaining or strikes to gain more from the employer. As indicated earlier, sometimes organizations have both union and non-union voice forms (e.g., collective bargaining over wages and hours, joint employee–management consultation over process improvement), and this combination we treat as “most voice” and locate it at the high end of the continuum.

The fact that NER is in the relative middle of the voice continuum provides insight on why it is controversial and relatively fragile. As viewed by employers, NER is a significant delegation of authority, control, and influence to employees, and many shy away from it for this reason. Employees, on the other hand, often see NER as givi...