eBook - ePub

The Semantic Turn

A New Foundation for Design

Klaus Krippendorff

This is a test

- 368 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Semantic Turn

A New Foundation for Design

Klaus Krippendorff

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Responding to cultural demands for meaning, user-friendliness, and fun as well as the opportunities of the emerging information society, The Semantic Turn boldly outlines a new science for design that gives designers previously unavailable grounds on which to state their claims and validate their designs. It sets the stage by reviewing the h

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Semantic Turn un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Semantic Turn de Klaus Krippendorff en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medicine y Psychiatry & Mental Health. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

chapter one

History and aim

To provide a suitable context for this book, I start with a brief account of how the idea of product semantics developed, then review how design problems and the environments in which designers work have changed, and finally, I focus on what needs to be done.

1.1 Brief history of product semantics

Product semantics was a collaboration of several thoughtful designers and the starting point for the proposal to redesign design. The term first appeared in the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA)’s journal Innovation (Krippendorff and Butter, 1984). Reinhart Butter and I defined “product semantics” as both an inquiry into the symbolic qualities of things and as a design tool to improve these cultural qualities. Because this dual purpose conflicted with the epistemology of semiotics, we went back to the Greek word for the study of meanings, or semantics, and added product as our initial concern. This special issue on product semantics brought together the works of several designers and design researchers. They discussed industrial products, not as photogenic objects of exemplary aesthetic qualities, but regarding what they could say to their users, as communications, as having meanings. The contributors to this special issue sensed a new beginning for design, one that recognized a basic concern if not the basic concern of designers.

For me, however, the idea of a semantics for design goes back even further than this publishing collaboration, to two papers (Krippendorff, 1961a, b) written concurrently with my graduate thesis at the Ulm School of Design* (Krippendorff, 1961c). The idea of this thesis hibernated until the early 1980s when Reinhart Butter, with whom I had remained in contact regarding these ideas, thought it timely to join efforts and edit this special Innovation issue.

Immediately following the 1984 publication of Innovation, IDSA invited interested industrial designers to a summer workshop at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, conducted by Reinhart Butter, Uri Friedländer, Michael McCoy, John Rheinfrank, and myself. This workshop proved not only successful, but it attracted the attention of Robert Blaich, then Director of Corporate Design at Philips Corporation in Eindhoven, The Netherlands, where it was repeated, with only a minor change in participants. Philips’ designers from all over the world attended. This repeat performance gave Philips Corporate Design not only several product ideas (one would become the by-now famous roller radio), but, more importantly, this engagement created a new momentum, a new conceptual orientation, a new methodological basis, and a new organizational identity.*

By 1987, these ideas found worldwide resonance. The Industrial Design Centre at the Indian Institute for Technology (IIT) in Bombay invited design practitioners and scholars to a major conference on product semantics called “Arthaya,” an ancient Hindi word for meaning. Designers in multilanguage and multicultural India, with its visually rich mythologies, embraced the semantic turn with open arms for it promised to provide concepts, methods, and criteria that would not only serve industry’s interests but moreover would respect diverse sociocultural traditions and support indigenous forms of development. The universalism prevailing in the industrialized West traditionally had denigrated cultural diversity as a sign of underdevelopment and deficient rationality. The new acceptance of diverse cultural meanings of industrial artifacts moved design into the center of cultural development projects.

In 1989, Reinhart Butter and I edited a double issue of Design Issues (Krippendorff and Butter, 1989), which has since become a standard reference in the product semantics literature.** Here, we agreed to define product semantics as both:

- A systematic inquiry into how people attribute meanings to artifacts and interact with them accordingly

and

- A vocabulary and methodology for designing artifacts in view of the meanings they could acquire for their users and the communities of their stakeholders.

Definitions focus attention on what matters. We wanted to avoid mentalistic conceptions of meanings and sought instead to embed meanings in how artifacts are actually used, in a meaning-action circularity. We soon realized that our concept of meaning could not be limited to what users do with artifacts but must also apply to what designers do with them, although designers have their own meaning-action circularities. Finally, we wanted product semantics to be not a mere scientific descriptive effort but one that provided designers with conceptual tools, a vocabulary for constructively intervening in processes of meaning making. The publication coincidentally arrived just in time for the first European workshop on product semantics, organized by Helsinki’s University of Art and Design, at that time called the University of Industrial Arts. Here, Hans-Jürgen Lannoch and Robert Blaich joined the original group. The reception of these ideas (Väkevä, 1990; Vihma 1990a, b) spawned further Helsinki workshops, conferences with an increasing number of international participants, and publications (Vihma, 1992; Tahkokallio and Vihma, 1995). This university has remained a leading player in these developments ever since.

In addition, workshops have been held in Colombia, Germany, Switzerland, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and the United States. Semantics has found its way into the curricula of several design departments, notably at the Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Cranbrook, Michigan, and at the University of the Arts workbook (Krippendorff, 1993b) that has been reproduced and is currently being used in several other educational settings.

In 1996, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) sponsored a major conference to see how designers could contribute to making information technologies more widely available. NSF was looking for consensus on a national agenda or at least policy recommendations for a national role for Design in the Age of Information. The report, by that name, (Krippendorff, 1997) outlined rising technological opportunities, new design principles, and educational challenges; it recommended several major research undertakings. The design principles for the new information technologies turned almost exclusively around issues of semantics: understanding, meaning, and interfaces that enable cooperation, honor diversity, even support creative conflicts. The educational recommendations focused on the demands of human-centered design curricula, and the research agenda identified significant knowledge gaps that research dollars might bridge. Semantics was recognized as a key to making the benefits of the ongoing information revolution more widely accessible.

In the summer of the same year, 1996, the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York invited a small group of design historians, psychologists, communication scholars, architects, art editors, and museum curators to an interdisciplinary conference and workshop on “The Meaning of Things.” This leading U.S. design museum realized meaning as a new unifying concept in design. Participants searched for common threads through such cultural artifacts as public spaces, industrial products, museums exhibitions, Holocaust memorials, computer interfaces, and folklore.

In the fall of 1998, Siemens AG and BMW sponsored a special symposium in München, Germany, entitled “Semantics in Design.” It brought together 12 designers and experts from such fields as communication, consumer research, innovation research, and new media technologies to talk about their approaches to how artifacts acquire meaning. This workshop realized meaning as a central concern for design while acknowledging several vocabularies, which I elaborate on later, to deal with its conceptual challenges.

Emotions have since become increasingly important aspects of semantics. The 1994 conference in Helsinki, already mentioned, addressed this idea in a workshop themed “Pleasure or Responsibility.” Then in 2001, an International Conference on Affective Human Factors Design (Helander et al., 2001) brought human factors researchers together in Singapore. I delivered a keynote address on “Intrinsic Motivation and Human-Centered Design” (Krippendorff, 2004b). The question of how and which emotions are invoked while using artifacts naturally follows the question of what artifacts could mean. Many papers, therefore, explored issues of semantics, including a Japanese approach to it, called kensai engineering. The conference was repeated in 2003. Meanwhile, Donald Norman (2004) wrote a popular book entitled Emotional Design.

In addition to the works just described, there were parallel developments. One is an attempt within the Hochschule für Gestaltung Offenbach to develop what is called a Theory of Product Language. It has resulted in several unfortunately inaccessible monographs, among them one by Richard Fischer (1984) on “Sign-Functions” and one by Jochen Gros (1987) on “Symbol-Functions.” Dagmar Steffen (2000) edited a comprehensive account of this theory. In Section 8.7, I comment on this approach. There also exists a proprietary in-house guide by Siemens (München, Germany) based on the metaphorical distinction between the form and the content of products (Käo and Lengert, 1984).

Semantics is attracting the attention of marketing too, pursuing the idea that meanings could “add value” to industrial products (Karmasin, 1993, 1994). There are at least six dissertations written on the subject.* Two other—until recently, unknown,—precursors of the semantic turn could be seen in works by Ellinger (1966), who developed the barely recognized idea that products have to convey the information needed to find their way to consumers, and by Abend (1973), who proposed to measure various product appearances. Perhaps also worth referring to was an effort in the 1960s, particularly in Italy, to address issues of meaning in architecture (Bunt and Jencks, 1980). Martin Krampen’s (1979) work on meanings in the urban environment must be mentioned in this connection as well. Norman (1988, 1998), while framing the issues in psychological terms, had similar aims. A recent book on the economic perspective on design (Gerdum, 1999) moved meaning and product semantics into the center of explanations of a cultural dynamics of artifacts. Obviously, the semantic turn has many sprouts and is rooted in fertile ground.

Some of these developments may be traced to seeds planted in the 1960s at the Ulm School of Design about which I say more in Chapter 9. It surely is no accident that Butter, Fischer, Lannoch, Krampen, and I started our

1.2 Trajectory of artificiality

As suggested in the foreword and overview, the industrial revolution managed to define design in relation to the mass production of material or, in the case of graphics, informative artifacts. In the belief that technological development would improve the quality of life for everyone, and committed to contribute aesthetically to material culture, designers worked without reflecting on their role in the larger context of expanding Western industrial ideals and replacing different cultural traditions elsewhere. There almost always was a schism between what designers believed they did and what they did in fact. The Bauhaus, for example, assertedly aiming at humanizing mass culture, managed to convert only very few of its designs into mass products. Instead, fueled by a fascination with geometrical forms and nonrepresentational (abstract and experimental) art objects, it provided museums with its unique designs. The Ulm school, the Bauhaus successor, fully embraced mass production, even in its architecture department, and was successful in shaping post-World War II industrial culture. However, it did not realize that it thrived on an emerging postwar cultural elites’ need to distinguish itself from the war generation with the help of new kinds of consumer products. When their demands In anthropology and design by Diaz-Kommonen (2002).came to be fulfilled, support for the school vanished and it closed. (This is not to suggest that this was the only reason for its demise, however.) Despite these vastly different efforts to situate design, virtually all of them subscribed to a functionalism, encapsulated in Louis Sullivan’s (1896) dictum:

Form Follows Function

This dictum, elevated to a design principle, entails the belief that the form of tangible products would emerge naturally from a clear understanding of the function they are to serve. It does not question what they are to serve, where functions come from, and the legitimacy of those who define them for designers to start with. It signals designers’ blind acceptance of the role they are assigned by society and by their industrial employers in particular. This dictum also reflects a hierarchical society in which specifications are written on the top and handed down or taken for granted, as if coming from an invisible authority. In a scathing critique, Jan Michl (1995) characterizes the notion of a function as a carte blanche, a metaphysical concept, that architects and designers could use freely to justify almost anything, their designs as well as objects of nature (Krippendorff and Butter, 1993)—provided it stayed within well-established conceptual structures. The dictum is still widely believed and frequently recited. As of May 13, 2005, a Google search of “form follows function” yielded 122,000 hits. The semantic turn challenges designers’ blind submission to a stable functionalist social order, which is anachronistic to the kind of society experienced today.

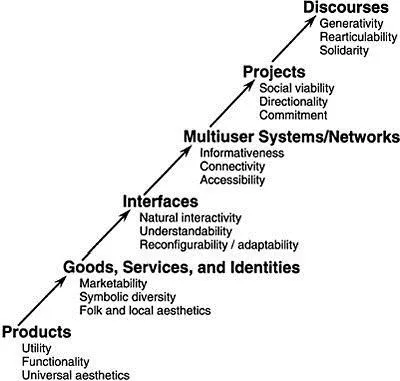

It is fair to say that the today’s world is more complex, more immaterial, and more public than the world out of which this dictum grew. Design evolved beyond what the dictum could handle and designers are facing unprecedented challenges. Figure 1.1 shows a trajectory of such design problems. It starts with the design of material products and continues a progression of five major kinds of artifacts, each adding to what designers can do. This trajectory is not intended to describe irreversible steps but phases of extending design considerations to essentially new kinds of artifacts, each building upon and rearticulating the preceding kinds and adding new design criteria, thus generating a history in progress:

Figure 1.1 Trajectory of artificiality.

1.2.1 Products

Products, by dictionary definition, are what producers produce. The word refers to the end results of a manufacturing process. Designing products means surrendering to manufacturers’ criteria; for example, that they are producible at a price below what they can fetch on the market, and by the rational extension of this profit motive, that they have utility to their users as well. This producer-product-profit logic dominated decision-making during the industrial era (Simon, 1969/2001:25–49), an era of scarce material resources and hierarchical social structures, coupled with an unwavering belief in technological progress, not to mention frequent wars and increasing poverty for large sections of the population.

Designers could, of course, and good ones often did not stop at aesthetic considerations and improved on producers’ product specifications, but because it was the producers who assumed the financial risk of failures, it ultimately was the producers’ intentions that mattered. Misuses and misapplications were discouraged, which left producers blameless when people got in trouble because they used their products in unintended ways. To prevent unintended and incompetent uses, people could take courses, especially in the use of artifacts considered complex at that time, like typewriting or using washing machines, and it was not unusual for manufacturers to train and certify experts in what they manufactured. All of these measures demonstrate that producers were in charge of “correct” usage, and when designers talked about functional products, they had adopted producers’ intentions as their design criteria.

With their affinity to art, product designers assumed responsibility largely for covering ugly engineered mechanisms with pleasing forms. “Form givers” is the literal translation of the German “Formgeber,” used at least until the 1970s for the English “designer.” Much of design discourse concerned forms—good forms, pleasing forms—governed by an ever-shifting aesthetics. It is precisely because designers had to justify the aesthetics of mass-produced products, products that would ideally be of use to everyone, not individual works of art, that the aesthetics of industrial products had to be a universalist aesthetics, one that was believed to be culture free and valid for everyone. The emergence of a universalist aesthetics led the industrialized West not only to deny its own cultural past, but also to render other, espec...

Índice

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction and Overview

- Chapter 1 History and aim

- Chapter 2 Basic concepts of human-centered design

- Chapter 3 Meaning of artifacts in use

- Chapter 4 Meaning of artifacts in language

- Chapter 5 Meaning in the lives of artifacts

- Chapter 6 Meaning in an ecology of artifacts

- Chapter 7 Design methods, research, and a science for design

- Chapter 8 Distantiations

- Chapter 9 Roots in the Ulm School of Design?

- References

- Credits

- About the Author

Estilos de citas para The Semantic Turn

APA 6 Citation

Krippendorff, K. (2005). The Semantic Turn (1st ed.). CRC Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1710959/the-semantic-turn-a-new-foundation-for-design-pdf (Original work published 2005)

Chicago Citation

Krippendorff, Klaus. (2005) 2005. The Semantic Turn. 1st ed. CRC Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/1710959/the-semantic-turn-a-new-foundation-for-design-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Krippendorff, K. (2005) The Semantic Turn. 1st edn. CRC Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1710959/the-semantic-turn-a-new-foundation-for-design-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Krippendorff, Klaus. The Semantic Turn. 1st ed. CRC Press, 2005. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.