Skin Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

Mohammad Albanna,James H Holmes IV

- 466 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

Skin Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

Mohammad Albanna,James H Holmes IV

Información del libro

The skin is the largest human organ system. Loss of skin integrity due to injury or illness results in a substantial physiologic imbalance and ultimately in severe disability or death. From burn victims to surgical scars and plastic surgery, the therapies resulting from skin tissue engineering and regenerative medicine are important to a broad spectrum of patients.

Skin Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine provides a translational link for biomedical researchers across fields to understand the inter-disciplinary approaches which expanded available therapies for patients and additional research collaboration. This work expands on the primary literature on the state of the art of cell therapies and biomaterials to review the most widely used surgical therapies for the specific clinical scenarios.

- Explores cellular and molecular processes of wound healing, scar formation, and dermal repair

- Includes examples of animal models for wound healing and translation to the clinical world

- Presents the current state of, and clinical opportunities for, extracellular matrices, natural biomaterials, synthetic biomaterials, biologic skin substitutes, and adult and fetal stem and skin cells for skin regenerative therapies and wound management

- Discusses new innovative approaches for wound healing including skin bioprinting and directed cellular therapies

Preguntas frecuentes

Información

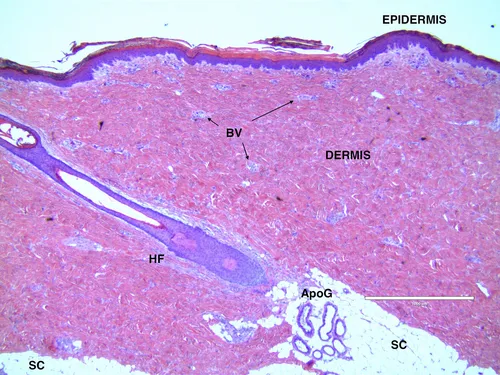

Anatomy, Physiology, Histology, and Immunohistochemistry of Human Skin

Abstract

Keywords

Basement membrane; Dermis; Epidermis; Hypodermis; Keratinocyte; Melanocyte; Vasculature; Wound healingIntroduction

Skin Anatomy, Histology, and Physiology

Epidermis

Índice

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Chapter 1. Anatomy, Physiology, Histology, and Immunohistochemistry of Human Skin

- Chapter 2. Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Healing and Skin Regeneration

- Chapter 3. Tissue Processing and Staining for Histological Analyses

- Chapter 4. Clinical Management of Wound Healing and Hypertrophic Scarring

- Chapter 5. Process Development and Manufacturing of Human and Animal Acellular Dermal Matrices

- Chapter 6. Clinical Applications of Acellular Dermal Matrices in Reconstructive Surgery

- Chapter 7. Advances in Acellular Extracellular Matrices (ECM) for Wound Healing

- Chapter 8. Natural Biomaterials for Skin Tissue Engineering

- Chapter 9. Synthetic Biomaterials for Skin Tissue Engineering

- Chapter 10. Hybrid Biomaterials for Skin Tissue Engineering

- Chapter 11. Biologic Skin Substitutes

- Chapter 12. Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Wound Assessment and Treatment Approach

- Chapter 13. Current Innovations for the Treatment of Chronic Wounds

- Chapter 14. The Surgical Management of Burn Wounds

- Chapter 15. Advances in Isolation and Expansion of Human Cells for Clinical Applications

- Chapter 16. Cutaneous Applications of Stem Cells for Skin Tissue Engineering

- Chapter 17. Advances in Biopharmaceutical Agents and Growth Factors for Wound Healing and Scarring

- Chapter 18. Skin Models for Drug Development and Biopharmaceutical Industry

- Chapter 19. Animal Models for Wound Healing

- Chapter 20. Human Skin Bioprinting: Trajectory and Advances

- Chapter 21. Translational Research of Skin Substitutes and Wound Healing Products

- Index