Chapter 1

Antoni Gaudí and his time

The historical context

The period in history between the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Spain and, specifically, in Catalonia, was one of significant change and upheaval. The country was transformed by the industrial revolution and growing migration from rural zones to the cities. As a consequence, an entrepreneurial urban bourgeoisie began to emerge alongside an uneasy working class subject to the economic conditions of the day. Barcelona became a major urban centre for both production and politics. When its population surpassed 200,000 the historic city walls had to be breached, giving rise in 1859 to creation of the Eixample district as part of the plan devised by the civil engineer Ildefons Cerdà which would enable the orderly, uniform expansion of the metropolis. However, the event that would breathe new life into Catalonia would be the 1888 Barcelona World’s Fair which, over and above the tremendous advances it introduced in the technological and business fields, also brought electrification of the country, originating an era of prosperity which led to Catalonia being known as the factory of Spain. However, this industrialisation process also entailed significant changes in social structure, which led to either confrontation or agreement between workers and factory owners, in other words, between proletariat and bourgeoisie, which opted increasingly for political Catalanism. This movement would be the driving force behind numerous important cultural projects, benefitting from the repatriation of capital from Cuba and the Philippines due, in particular, to the loss of overseas colonies in 1898.

In short, by the early 20th century the social situation had become extremely strained and in the midst of a huge crisis in production and trade in 1902 which resulted in the closure of numerous factories, a general strike was called. The situation remained tense and some years later, in July 1909, a protest against the embarkation of troops bound for Morocco derived into one of the most serious social uprisings ever experienced in the city: the Setmana Tràgica (Tragic Week).

The CNT trade union was constituted in Barcelona in 1911, soon becoming the most active revolutionary anarchist organisation of its kind; that same year the bourgeoisie, especially the textile industry, rallied around their guilds, creating a robust economic and social structure. It was the prosperity of these years that facilitated major acts of philanthropy which would be materialised especially through architecture, be it civil, industrial or religious and which, in turn, fostered the arts and trades. Spanish neutrality in the First World War favoured manufacturing in general, and the cotton industry in particular, thanks to which Catalonia experienced several years of fervent economic activity. This would end with the armistice, throwing the country into a new period of instability and confrontation between the working class and the bourgeoisie. A situation that would be abruptly resolved in 1923 by the coup d’état led by General Primo de Rivera who, with the consent of King Alfonso XIII, proceeded to establish a dictatorship.

Thus, these were dynamic, conflictive times, charged with enthusiasm and tensions between past and future; times of tension between progressive ideas and conservative currents, of change in social models and of the birth of great institutions and organisations that would shape Catalonia over the following decades. These included the Associació Protectora de l’Ensenyança Catalana, the Lliga Espiritual de la Mare de Déu de Montserrat, the Orfeó Català, Fútbol Club Barcelona, the Escola Moderna de Ferrer i Guàrdia, the Ateneu Enciclopèdic Popular and the Estudis Universitaris Catalans, as well as a series of newspapers and magazines whose pages would define 20th century Catalanism, a current which began with the Renaixença of the 19th century and which found its culmination in Modernisme and Noucentisme. This set of circumstances marked Gaudí’s career and his major projects, because though he was determined to continue building he suffered bouts of extreme euphoria, alternating with others of deep depression, which obliged him to take sporadic periods of convalescence.

A biographical glimpse

Gaudí was born on 25 June 1852. For some, this occurred in Reus, home town of his mother, Antònia Cornet i Bertrán, and for others it took place in Riudoms, the birthplace of his father, Francesc Gaudí i Serra. There has been a good deal of discussion on this point and new official documents have recently appeared that certify the physical birth of Gaudí in Reus, though there are also documents claiming that hours later he was baptised in the priory church of Sant Pere in Reus, having been brought there from Riudoms. Whatever the case may be, the four kilometres that separate the two towns should be no cause for dispute, because where Gaudí’s worldview left its mark was not on a particular town or city, but rather on this area of Catalonia as a whole. Another factor that influenced the way Gaudí’s mind worked lies in the fact that his father and both his grandfathers, Francesc Gaudí and Antoni Cornet, and even one of his great-grandfathers, were boilermakers, a trade into which Gaudí entered as a young man and which exercised decisive influence on him, because it helped him develop manual skills and gain a thorough knowledge of materials. It also stimulated his capacity to understand space and all things related to volumes, concaves and convexes, which in turn enabled him to switch with remarkable ease from two to three dimensions. Gaudí himself once said: “I have this ability to see space because I am the son, grandson and great-grandson of boilermakers. My father was a boilermaker; my grandfather too; my great-grandfather too; at my mother’s house they were also boilermakers; her grandfather was a coppersmith (which is the same as a boilermaker); a maternal grandfather was a sailor, who are also people of space and situation. All these generations of people so aware of space provide preparation. The boilermaker, who has to make a volume from a flat sheet. He has to have visualised the space before he starts. […] Boilermakers embrace the three [dimensions] and this creates, subconsciously, a command of space that not everyone possesses”. It is interesting to note that Gaudí did not feel he was a member of a privileged class; rather his mentality, like his origins, was clearly linked to the world of artisans, and thus his ethics, self-discipline, strength and conception of work were those associated with this social group.

Gaudí’s early schooling took place in Reus. First at an elementary school headed by master Francesc Berenguer, and from 1863 to 1868 at the Piarists’ school, where he studied baccalaureate and received traditional humanistic and religious education which would stay with him throughout his life. He excelled at the subjects of geometry and arithmetic, collaborated on the hand-written school magazine El arlequín, in which his first drawings –engravings in boxwood– appeared, and created the sets for a stage play, all of which highlighted his early aptitudes in the plastic arts. He moved to Barcelona in 1869 to initiate the preparatory cycle of architecture at the Instituto de Enseñanza Media high school that would enable him to enter the University of Barcelona Faculty of Sciences, where he completed the basic courses necessary to enrol in the newly founded Provincial School of Architecture of Barcelona. The school was pedagogically inspired in the French, École Polytechnique model, which paid special attention to sciences applied to construction, technologies and the historical and aesthetic knowledge of architectural languages.

| LA VANGUARDIA ARCHIVES (ALVG) / MARCEL·LA AGUILÓ • Mas de la Calderera in Riudoms, the family house where Gaudí spent long periods of his childhood |

Gaudí had many teachers at university, but for the influence they would have on his career we should highlight Elies Rogent i Amat, a historicist architect and the school’s director; Francisco de Paula del Villar, professor of composition and theory of art, with whom he would subsequently collaborate; Joan Torras, an expert in the application of metals in architecture; August Font, an eclectic traditionalist; Antoni Rovira i Rabassa, who introduced him to descriptive geometry and stereotomy, which the architect would develop widely throughout his career; and an extremely prominent figure in the history of Catalan architecture, Lluís Domènech i Montaner, who kept him abreast of the main centralEuropean architectural trends.

Gaudí’s academic record, which is conserved in the School of Architecture, shows that he was an irregular pupil obliged to repeat numerous subjects, but one who excelled with brilliant grades in those related to drawing, mathematics and handicrafts. Fortunately, sketches he made for ideas developed during his time as a student are conserved in the archives of the School of Architecture, including those corresponding to a jetty (1876), a fountain for Plaça Catalunya (1877), and his final-year project consisting in an assembly hall for the central university of Barcelona, which gained him the minimum qualification of “approved by majority”. Despite his erratic academic curriculum, Gaudí’s teachers succeeded in bringing out his talent and special vocation for architecture. During his studies they placed him as a draughtsman or assistant in various offices, such as that of the prestigious master builder Josep Fontserè, whom he helped on the project of the monumental waterfall in Barcelona’s Ciutadella Park, as well as on the park’s railings, the water deposit, the Museum of Natural Science and the Born Market. He also assisted the architects Leandre Serrallach and Francisco de Paula del Villar Lozano on the niche room of the Basilica of Montserrat, in addition to working with Joan Martorell i Montells.

These collaborations, together with the designs he made of an altar for Masnou church, the display cases for the Vilardell pharmacy, some items of furniture and the various projects he carried out for the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense meant that even before being awarded the official formal qualification of architect on 15 March 1878, everyone already recognised him as such. However, only from this moment would he have business cards printed to his own design with the address of his studio in Carrer del Call, in the very heart of historic Barcelona. Thus, it was in this office that the career began of a man who no-one would hesitate to qualify today as a vocational architect –he devoted himself wholly to his profession without interruptions for 48 years, from graduation until three days prior to his death in a traffic accident in 1926, at the age of 74. There can also be no question that Gaudí was an architect in the broader sense of the term: the creator of original spaces and extraordinary volumes, designer of furniture, urban planner and inventor of shapes that broke with the dictates of traditional architecture to open up new horizons in the field of art and construction.

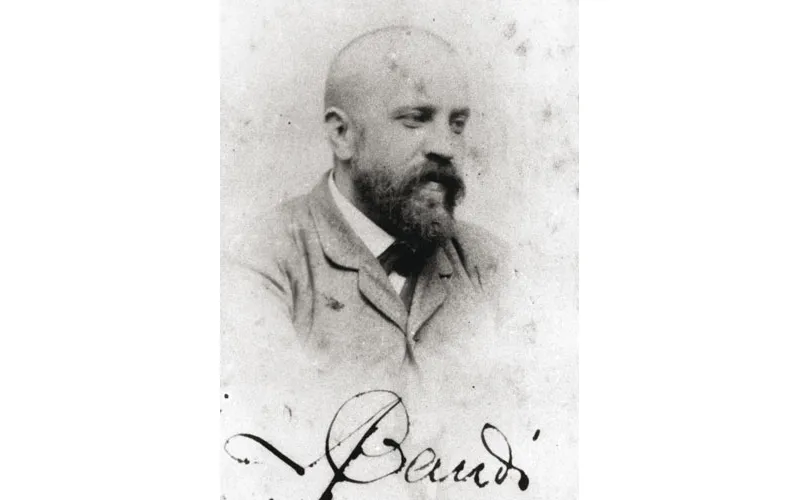

| ALVG • Gaudí at the age of 36, in an image from his admission card to the Barcelona World’s Fair of 1888 |

But many years would have to pass before reaching this point. First, and with his architect’s degree safely in his pocket, Gaudí set about broadening his knowledge, particularly of arts and crafts. He attached great importance to decorative elements and knew how to achieve authentic ornamental wonders using wood, iron, ceramics, glass and plaster applications that he incorporated so skilfully into his architecture they became one with it. His now proven ability and understanding of manual processes led him to collaborate with two artisans whom he met while working with Fontserè on the decorative aspects of the Ciutadella Park: the sculptor and modeller Llorenç Matamala, and Eudald Puntí, one of the foremost specialists in what was known as arts and artistic industries, which included work in iron, wood and glass. It was precisely in his workshop where the original wooden work table and metal applications designed for Gaudí’s office were produced, and where it seems he may have met the man who would become his greatest patron, Eusebi Güell. Previously, on a visit to the Spanish Pavilion at the 1878 Universal Exposition in Paris, Güell had discovered the glass display case that Gaudí had designed for the glove manufacturer Comella and which had also been built in Puntí’s workshop.

Also in 1878, Barcelona City Council asked Gaudí to design two models of lamp-posts to illuminate the city. Two examples of the model comprising six branches were erected in Plaça Reial and the three-branched version was situated in Pla de Palau, where they remain to this day. As from this moment, Gaudí’s name gained recognition and he received two significant commissions: a kiosk intended for the sale of flowers and including public urinals, which he designed in iron, marble and glass but which was finally never built, and design of the furniture for the pantheon-chapel that Antonio López López, the first Marquis of Comillas, had ordered to be built in Sobrellano (Santander). These projects would be followed by others of somewhat more importance, such as decoration of the Farmàcia Gibert on the corner of Plaça Catalunya and Carrer Fontanella. Gaudí designed the shop sign, display cases, marquetry counter and a wooden bench; works which were completed in 1879 but which, regrettably, disappeared when the pharmacy was demolished.

As a consequence of his relationship with the ecclesiastical world, which was prospering, he was also entrusted with the decoration of churches, such as that of Jesús-Maria in the town of Sant Andreu del Palomar –which now forms part of Barcelona– where in 1879 he executed an interesting Roman mosaic similar to that which he would later apply in the crypt of the church of Sagrada Família. He was also commissioned to draw up plans for the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament for the parish church of Alella, a project which was never completed, though Gaudí’s original drawing has survived.

It was in 1883, however, when he received the first commission to design an architectural project in the city of Barcelona: Casa Vicens. This would be followed by a series of important buildings, such as the pavilions at Finca Güell, the lavish Palau Güell, the Teresian School, Casa Calvet, Güell Park, Torre Bellesguard, Casa Batlló and La Pedrera, all in Barcelona. In addition to his most experimental work, the church at Colònia Güell in Santa Coloma de Cervelló, he also undertook the bleaching room at the Cooperativa Obrera Mataronense, El Capricho in Comillas (Santander), the Episcopal Palace in Astorga (León), the Casa de los Botines in León and the Güell wine cellar in El Garraf, until in ...