eBook - ePub

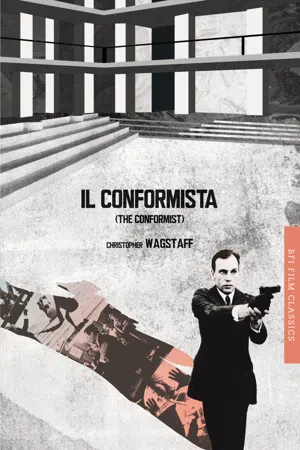

Il conformista (The Conformist)

Chris Wagstaff

This is a test

- 96 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Il conformista (The Conformist)

Chris Wagstaff

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Il Conformist has mesmerised audiences by Bertulocci's mastery of the telling, the beauty of the images, the camera work, its soundtrack, and the intensity with which the characters convey powerful psychic energies. This unique European film classic deserves no less the unique perspective brought to it here by Christopher Wagstaff's expert eye.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Il conformista (The Conformist) un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Il conformista (The Conformist) de Chris Wagstaff en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Media & Performing Arts y Film & Video. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

‘Il conformista’

Background

In 1925, the young Alberto Moravia was convalescing from tuberculosis in a sanatorium in the Dolomites when his cousin, Carlo Rosselli, drove up from Rome to visit him. Both were anti-fascists, but Carlo’s anti-fascism took the form of a liberal idealism (we would call him a social democrat, and he was very close to the British Labour Party at the time), in which an enlightened pursuit of individual self-interest was seen as gradually leading to a more rational and equal society. From this perspective, fascism was an aberration, a failure to understand how real historical progress actually took place, and a deviant digression in the march of history. Carlo and his brother Nello founded a Paris-based anti-fascist movement called Giustizia e Libertà (Freedom and Justice), many of whose members fled from fascist repression into exile in France. Meanwhile, however, Alberto’s anti-fascist political ideas were much closer to those of the Italian Communist Party, according to which fascism was nothing other than the true face of bourgeois capitalism. Faced with opposition from the working classes, the ruling classes abandoned the pretence of democratic social consensus and took up the weapon of violent, repressive domination. Basically, if workers tried to go on strike, fascist thugs would be hired to beat them up. For someone like Alberto, fascism was not a historical aberration, but was the true, clearly visible reality of liberal capitalist society, undisguised by cultural and ideological smokescreens. The opponents of fascism were, therefore, not bourgeois intellectuals, who were in no way threatened economically by the way the fascists were ruling, but the working classes, whose pay and working conditions were kept down in order that the bourgeoisie could extract more profit from them. The way to fight fascism was by direct struggle, in the factories and in political organisations. Seen from this Marxist perspective, while the intellectuals of the Giustizia e Libertà movement might well criticise the philosophy of fascism, their anti-Marxism meant that their objections to fascism were more a matter of aesthetics and philosophy than of material repression: their own freedoms were curtailed more by censorship and vulgarity than by economic deprivation.

I am exaggerating and compressing here. What we know of Alberto Moravia’s political position comes from things that he said much later in life; and I am aiming above all to clarify the politics of the film that Bertolucci would later make of Alberto’s novel about the death of his cousin.1 Because, on 9 June 1937, the fascist secret service, fed up with the anti-fascist propaganda activities of the Rosselli brothers emanating from Paris, arranged for local thugs in the Cagoule to murder them in the French countryside, which they did by blocking their car from in front and behind, in a way similar to the assassination of Professor Quadri in Il conformista. In 1949, Moravia wrote a novel around the murder of his cousin, with the aim of writing about fascism from the inside, from the perspective of a fascist, rather than from the external perspective of an anti-fascist critic of the regime. He called the novel Il conformista (The Conformist), and it was published in 1951. It gives a linear, chronological account of how the child, Marcello Clerici, becomes aware of an aggressive impulse inside him, acting like an inexorable Fate, which is destined to make him graduate from destroying plants, to killing animals, and eventually to becoming a murderer. He is won over by the offer of a pistol from a homosexual chauffeur and, confused by the man’s advances, shoots him. Checking the newspapers confirms his belief that he has killed him. To cover up his abnormality as a murderer and his doubts about his sexuality, he marries the most conventional middle-class girl he can find, and embraces orthodox fascism to the extent of enrolling in the political police, with the plan of spying on his former philosophy professor, who is directing anti-fascist activities from exile in Paris. On his honeymoon, he leads his secret service colleague to the professor, and returns to Rome, where he later hears how the murder of the professor and his wife took place. The story jumps to July 1943 and the fall of Mussolini, when in a park in Rome he encounters in living flesh and blood the very chauffeur he thought he had killed. Evacuating the city, his car is strafed by a fighter aircraft, acting like a deus ex machina, and he and his wife and daughter are killed.

Moravia’s novel was nourished in rich soil. In 1940, Jean-Paul Sartre had been awarded the Prix du roman populiste for his 1939 collection of five short stories entitled Le Mur, the most substantial of which was a novella, L’Enfance d’un chef (The Childhood of a Leader), telling the story of Lucien, the son of a factory owner, who grows up insecure about his identity, but would like to be a leader like his father.2 He reads Freud, and has an unsatisfactory homosexual experience with an older man, which leads him to compensate by taking up rather half-heartedly with a woman. He also falls in with right-wing anti-Semitic students and participates in violent attacks on Jews, escalating to murder. He sees his future as a leader of France.

Moravia himself writes in 1941 a short novel, Agostino, published in 1944, on a clearly oedipal theme about a youth who is also disturbed by a homosexual encounter. Moreover, it is almost inconceivable that Moravia’s interest in Freudian psychoanalysis didn’t bring him into contact with Freud’s most famous case history, that of ‘The Wolf Man’, revolving around oedipal conflicts, repressed childhood seduction and insecure sexual orientation. A highly regarded fellow collaborator on literary journals, Carlo Emilio Gadda, had written an essay-novel in 1945, Eros e Priapo, in which he carried out what one can only call a hugely strenuous and vituperative psychoanalysis of the phallocentrism and cult of virility of Mussolini and the Fascist Party. Some parts of it were published in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s literary journal Officina in 1955, but the novel as a whole was not finally published until 1967, creating a furore in 1968, shortly before Bertolucci was to embark upon making Il conformista.

In 1969, Bernardo Bertolucci was making a film to be shown on television, loosely based on a Borges short story, called Strategia del ragno (The Spider’s Stratagem), in which a young man returns to his home town to investigate the murder of his anti-fascist father, a middle-class intellectual. He learns that his father and a group of conspirators had planned to shoot Mussolini at the climax of a performance of Verdi’s Rigoletto in the town’s opera house. Instead, according to all accounts, his father had been shot in his box at the opera by a fascist, and was celebrated in the town as an anti-fascist martyr. The son discovers that in actual fact the father had chickened out of the planned direct action against fascism (the shooting of Mussolini), and had told the police about the plot, whereupon Mussolini’s visit to the town had been cancelled. He had confessed his betrayal to his fellow conspirators, and had made them the following proposal: that they should shoot him in the opera house, just as they had intended to shoot Mussolini, but they should put the blame on fascists, and therefore create a martyr who would dominate the history and culture of the town for decades into the future. I shall add here a little interpretation, because the film is never explicit about why the father betrays the plot to kill Mussolini. And the suggested interpretation relates to what I have just said about Il conformista above. The father is a middle-class intellectual anti-fascist who is threatened by fascism not materially and economically but above all aesthetically – it is vulgar. Bourgeois intellectuals do not go around shooting people to achieve their goals, because it is much more effective to create a story, a narrative, a ‘history’ which will determine future generations’ view of how the world is. So the father arranges a performance whose message persists into posterity. Bertolucci ends his film by having the son find it impossible to reveal the truth that he has uncovered. The historical account of a martyr to anti-fascism is allowed to persist unchallenged. And this is Bertolucci’s way of expressing his rebellion against the experience of a young Marxist intellectual trapped in a mythical or legendary version of Italy’s political history in 1969, according to which the previous generation had been characterised by its ‘resistance’ to fascism.

While he was getting ready to shoot Strategia (it was shot in the summer of 1969), his girlfriend, Mapi (Maria Paola) Maino (an expert in design between the wars), was reading Moravia’s novel Il conformista, and recounted to him in detail the story of the book. Bertolucci was so taken by the story that, before even reading the novel himself, he took the proposal for a film to Paramount’s Italian production affiliate, Mars Film. Paramount approved the idea in September 1969, and arranged for the film to be financed to the tune of just under $1 million by a newly formed joint venture between Paramount and Universal for the distribution of their films outside the United States called CIC (Cinema International Corporation). To benefit from the support that European countries gave to their own national cinema industries, the funds were funnelled through an Italian production company, Mars Film, and a French company, Marianne Productions, in an Italo-French co-production arrangement, with the co-participation of the German company Maran Film. Shutting himself away for a month with a typewriter and a copy of the novel, Bertolucci produced a script, and that autumn work on the film began (completed in January 1970), with Bernardo’s cousin, Giovanni Bertolucci, in charge of production. Bernardo’s transposition of the novel into film was in some respects quite a free one, but it was enthusiastically greeted by Moravia himself, who was a close friend of the 28-year-old film-maker.

Just as Moravia’s novel did not blossom in a vacuum, neither did Bertolucci’s film. For a number of years after World War II, Italians had been reluctant to examine the past, and in particular the two decades of fascism, and an orthodoxy reigned in Italy, according to which the fall of fascism, the Allied liberation and above all the Resistance movement constituted a historical watershed, dividing authoritarian, totalitarian fascist Italy from the post-war democratic Republic. Italians had rejected fascism in what amounted to a civil war, and the wounds should be quietly left to heal. In the 1960s, writers, historians and political scientists began seriously challenging this vision, investigating whether it really was plausible to assert a break between fascism and post-war Italy. Rather than treating fascism as some unknown, untouchable horror to be hidden away, they asserted the need for study and research, investigation and discussion. In the second half of the 1960s, a younger generation challenged the myth of the Resistance as legitimising the authority of their parents’ generation. All began acknowledging a greater degree of continuity between fascism and bourgeois free-market capitalism, and started seriously questioning whether Italian society really had risen up against fascism and founded a true democracy on the basis of that resistance. Bertolucci’s two films of 1970, Strategia del ragno and Il conformista, are key cultural manifestations of this intellectual climate.

It would, moreover, be difficult to exaggerate how closely knit the Italian cultural and artistic world was in the 1960s. The young Bertolucci was part of Moravia’s circle, which included Pier Paolo Pasolini, the homosexual poet, writer, scriptwriter and film-maker, with whom Bertolucci worked closely. Mauro Bolognini filmed Moravia’s Agostino in 1962, highlighting its homoerotic content. The Ferrarese writer Giorgio Bassani, working for the same literary reviews as Moravia, published in 1956 a volume of five short stories, one of which Pasolini helped adapt for Florestano Vancini’s 1960 film, La lunga notte del ’43 (It Happened in ’43), where fascist betrayal is linked to sexual inadequacy, and where the protagonist witnesses fascist murders and does nothing. Bassani’s 1962 novel, Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini (The Garden of the Finzi-Continis), about fascist persecution of the Jews in Ferrara went through a number of attempted adaptations, until in 1968 it was entrusted to the veteran neorealist director Vittorio De Sica, whose film of the novel was released in 1970, starring the same Dominique Sanda whom Bertolucci would choose for his film, alongside Helmut Berger, Visconti’s companion, in the role of a repressed homosexual. As mentioned earlier, the publication in 1967 of Gadda’s sexual psychoanalysis of fascism in Eros e Priapo, which had first appeared in Pasolini’s literary review, caused a sensation. Everybody was reading Freud. In 1969, Bernardo embarked on a long course of psychoanalysis, to which he partly attributes the explosion of creativity which led to his subsequent films.

Collaborators

In his previous films, Bertolucci had used Roberto Perpignani as his editor, but Giovanni Bertolucci, the executive producer of Il conformista, insisted that this time Bernardo should accept as editor Franco (Kim) Arcalli, who had worked as scriptwriter with Tinto Brass and as an innovative editor on the films of Giulio Questi. Bertolucci himself is the first to admit the enormous influence Kim had on Il conformista, as will become amply evident when we begin to examine the film. Arcalli’s pupil, Gabriella Cristiani (who went on to edit Bertolucci’s films after Arcalli’s death), goes to the heart of his method:

Kim didn’t assault so much the filmed material itself as the structure. He intervened strongly on the structure. Normally editors do it after the first rough cut. Instead Kim, being also a scriptwriter, did it straightaway. … His slogan was ‘Let’s turn everything upside down!’ … He didn’t just limit himself to trimming and linking together the shots; he bothered about the structure and the narrative of the film.3

The cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro, was something of an enfant prodige in his profession, rapidly rising from student at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, to a...

Índice

- Title Page

- Contents

- Preface

- ‘Il conformista’

- Notes

- Credits

- Select Bibliography

- eCopyright

Estilos de citas para Il conformista (The Conformist)

APA 6 Citation

Wagstaff, C. (2019). Il conformista (The Conformist) (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1978468/il-conformista-the-conformist-pdf (Original work published 2019)

Chicago Citation

Wagstaff, Chris. (2019) 2019. Il Conformista (The Conformist). 1st ed. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://www.perlego.com/book/1978468/il-conformista-the-conformist-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Wagstaff, C. (2019) Il conformista (The Conformist). 1st edn. Bloomsbury Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1978468/il-conformista-the-conformist-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Wagstaff, Chris. Il Conformista (The Conformist). 1st ed. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.