![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Occupy Movement

Civil disobedience has become an endangered concept. Or at least that was the case until a wave of mass non-violent dissent hit North Africa, parts of South-West Asia, Western Europe and North America during 2011, raising all sorts of issues about how to understand contemporary political unrest as well as bringing the legitimacy of economic and political institutions into question. Even at the time, an obvious case could be made for regarding a large number of the protests as civil disobedience, but some commentators were cautious about doing so. They raised concerns about the relevance of the very idea of “civil disobedience” to something so new and so radical. In the course of this book I will attempt to allay these fears and to show that claims of civil disobedience have a vital, forward-looking role to play. Moreover, they can defensibly be made about a wide range of actions including many of those carried out by participants in the Occupy Movement in America and Western Europe. This opening chapter will be given over to a narrative account of the latter. My undisguised determination to vindicate the relevance of civil disobedience may, however, raise some concerns about the narrative, about the possibility that it could be skewed to support my overall conclusion. Like all such narratives of dissent, it may be challenged in point of detail and interpretation. There is, after all, a gap that invariably opens up between protest on the ground and subsequent reportage. Nonetheless, what follows is an outline of events that should be recognizable to participants and recognizable also to the vastly larger number of sympathetic onlookers whose connection to events was primarily through the popular media. In places, it may also capture a sense of the excitement of the moment.

Zuccotti Park

Between May and December 2011 public squares in Europe, parks in the US and even the precincts of St Paul’s Cathedral in London were occupied. Demonstrations in some of the world’s major cities took place on a scale that had been unknown for decades. At its height, the international focal point for this movement was the Occupy Wall Street camp in Zuccotti Park, a 33,000 feet-square area of ground in Lower Manhattan that was once, appropriately, called Liberty Plaza. Located only a block away from the site of the former World Trade Center, Zuccotti is a highly symbolic space. Its occupation in September 2011, only a week after the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, might have struck a more cautious or leadership-dominated movement as an unnecessary and provocative risk.

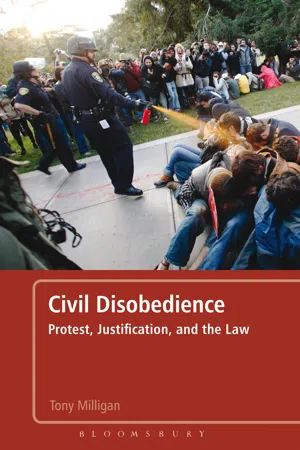

Zuccotti became the focal point by accident rather than design. The occupiers had considered elsewhere. There was talk about a small group trying to occupy the J. P. Morgan building, One Chase Manhattan Plaza, but the Park was more accessible, more public. At first the numbers were small; a couple of hundred protestors camped out by night and slightly larger numbers blocked traffic by day in an attempt to publicize their cause. The police responded with familiar tactics for urban control. Protestors were subjected to “kettling,” the forcible division of crowds into easily controllable groups followed by the immobilizing confinement of each group, often behind a wall of police officers wielding riot shields. Pepper spray, derived in part from capsicum chillies, was used to facilitate the process. Its use in civil disturbances is not unlike the herding of cattle as they are prodded to go first one way and then another. The impact of the spray can be both physical and moral. It disables individuals and can convince others that they face an overwhelming obstacle. Its use against the protestors in New York had the former impact but not always the latter.

Regularly used in the US since the early 1990s, the spray was first introduced as a way of applying non-lethal force in situations where immediate self-defense or the defense of others might be required. In practice, it has become a favored device of control, a ready multi-tasking solution in a can. It has been used with some regularity to force eco-protestors to unlock themselves from secured positions and, more controversially still, in combination with hoods and control chairs, against problem prisoners in correctional and custodial facilities.1 As a chemical agent, its use in warfare is illegal under international law. Within the US, state legislatures have differed about how it may reasonably be used. Protestors and legal counsel complain about the spray and some legislators accept that they have a point. If its use would be illegal on a battlefield, there is a question about why it should be considered legal on the streets.

Against the Occupy Wall Street protestors, video footage indicates that pepper spray was used in situations where there was clearly no threat, a dangerously provocative practice given that the spray has been continuously linked to deaths both in and out of custody.2 When used at close range against any of America’s 18.7 million asthma sufferers, hospitalization is a likely outcome.3 But good respiratory health offers little protection. One week into the occupation at Zuccotti, the web-based dissemination of a video showing police officers spraying a group of apparently helpless and penned-in female demonstrators resulted in a surge of popular support. By the following week, the NYPD was having to deal with thousands of protestors rather than hundreds. At one point a fleet of buses was brought in to ferry successive batches of arrested demonstrators off the Brooklyn Bridge.4

Buoyed by the combination of illegal protest and the largely peaceful occupation of public spaces, the movement spread nationally and internationally. By the end of October, a month after Occupy Wall Street protestors first moved into Zuccotti, there were an estimated 2,300 occupied zones in 2,000 cities worldwide.5 Protest camps of small, medium and large scale sprang up like mushrooms, varying in size from a handful of tents, hastily set up by eco-activists or anarchists, through to small tent-villages with performers and family groups. The larger camps resembled the outlying areas of a music festival and the atmosphere was, at times, similarly carnivalesque. With the crowds came the pickpockets and the petty criminals, then the sociologists and anthropologists keen to study the social composition and attitudes of the movement.6 In London, matters were on a smaller scale. The focal point was a tent village set up just below the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral in London. The protest camp was, nonetheless, given daily television coverage while church authorities argued over the respective merits of having the protestors removed by force or washing their hands and passing on the decision to Westminster City Council.

Then came the reaction. An international process of clearance began at the end of October with the forcible removal of the tents in Victoria Park, Ontario. A brief pause followed to avoid the potential flashpoint of Guy Fawkes night, then the curfews and forcible clearances resumed. Some of the camps were able to mount legal challenges, and some were too small to be dealt with in the first wave of removals. But key sites such as Zuccotti and Oakland were cleared, amid scuffles, arrests, attempted reoccupation and the ongoing use of pepper spray to control the predominantly non-violent but now clearly angry protestors. A striking feature of the movement, from the outset, was this ability to remain largely (but not exclusively) non-violent. Yet the participants in the Occupy Movement also exhibited a strong degree of ideological continuity with the anti-capitalist protesters who had forcibly taken over the streets of Seattle a decade earlier. Both established ground-level assemblies, institutions of direct democracy which were then contrasted with a hierarchical and compromised state-run democracy. Both involved an avoidance of formal leadership, a rejection of the idea that movements need charismatic figureheads who can enter into negotiations on their behalf.

The shifting balance of political forces

A variety of reasons may be offered to explain why the protests happened and why they took the form that they did in spite of the fact that many of those involved may not have been opposed to violence as a point of principle. One obvious influence that shaped the character of the Occupy Movement was the Arab Spring, the initially successful and similarly non-violent movement which had started in Tunisia in December 2010 with the self-immolation of a jobless student. Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after police tried to seize the vegetable cart that he was using to make a living. The sheer injustice of the act, and its surrounding circumstances, propelled him towards an act that carried echoes of more distant protests but which mirrored similar expressions of sheer despair in India and China over the preceding decade.7 The high point of the ensuing Arab protests came with the overthrow of dictatorships in Tunisia and Egypt by means of what looked like non-violent civil disobedience on a truly massive scale. What the Arab Spring seemed to show many commentators, against expectations to the contrary, was that protest without violence towards others could work in the face of apparently overwhelming and authoritarian state power. The point was made forcefully in the midst of these uprisings by the Burmese pro-democracy campaigner Aung San Suu Kyi when delivering her Reith Lectures for the BBC: “Gandhi’s teachings on non-violent civil resistance and the way in which he had put his theories into practice have become part of the working manual of those who would change authoritarian administrations through peaceful means. I was attracted to the way of non-violence, but not on moral grounds, as some believe. Only on practical political grounds.”8

A movement attracted to non-violence on such practical grounds could find room for admiration of Gandhi, Martin Luther King and, in England, Guy Fawkes. “V” masks became popular publicity symbols for the protests. Drawn from the film of the same name in which the anarchist anti-hero manages, with a little help from his friends, to blow up the Houses of Parliament, the masks featured regularly in the English newspapers. Ineffective at hiding identity, they helped to emphasize the anonymity and anti-authoritarianism of the many and the standing of the protests as carnivals of dissent. The wearing of a mask or the very act of sitting down and occupying space along with a body of others had become a radical act of defiance.

By the summer of 2011 the idea that mass non-violent protest could succeed where violence was likely to fail had become widespread. It matched well with the anti-violent ethos of at least some established radical political activists whose staple protests for almost a decade had involved opposition to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. While Aung San Suu Kyi’s lectures may not have been heard by anyone other than the usual listeners, she voiced a wider and growing belief that non-violent protest might not be a fundamental moral requirement, but that it could nonetheless deliver results as it had done in South Africa in the last days of apartheid. Perhaps it could not do so always or everywhere, but sometimes and especially at the present historical juncture. To an extent, the balance of political forces had swung protestors in favor of this idea. But, as with the Arab Spring, the immediate triggering factor which had led to the emergence of the Occupy Movement was economic. It took an international debt crisis and ensuing austerity measures to spark mass protest in the West. The same economic problems still retained the capacity to spark off a more violent response. Economic crisis and austerity had already triggered large and violent demonstrations in Iceland in 2009 and rioting in France during the summer of 2010. During 2011, peaceful protest and violent dissent were both features of the political landscape.

The key flashpoint in the French case was not, as it had been during the riots of 1968, issues that focused directly upon the young. The flashpoint was pensions, a soft target for a quick money grab by the State. In July 2010 the French government had announced their decision to push through a two-year increase in the retirement age and an increase in the pension contributions of state employees from 7.8 per cent to around 10.5 per cent of gross pay. Within weeks, workers at major oil refineries had struck over the issue. By October, roughly a third of the petrol stations in France had run dry. On 19 October a demonstration in support of the strikers spilled over into rioting in Paris. To the north of the city, a group of rioters advanced en masse, singing the Marseillaise before breaking through a police blockade to take control of the main access route to Charles De Gaulle airport. Rioting followed to the south, in Lyon. As the focus of action shifted away from the refineries, the protesters managed to close access to the airports at Clermont Ferrand to the south, Nantes to the west and Nice in the far south-east. The geographical spread was considerable.

At an international level, rioting driven by austerity measures rumbled on through 2010 and into 2011, notably in Greece, a country that had been effectively bankrupted by the debt crisis. Even in England, where violent protest had been at a low level for decades, there was an outbreak of rioting. In August, at the tail-end of the long summer of 2011, urban unrest broke out in London and then some of the cities of the Midlands and the North West following the shooting of a black youth by the police. The incident was not entirely isolated. Long-standing accusations of institutionalized police racism had, in the past, been coupled with similar incidents, albeit on an intermittent basis. The London Riots of 2011 began with a peaceful but angry blockade of a local police station in protest over the shooting. Following some questionable police decision-making, the demonstration turned violent. Extensive rioting followed. For the best part of a week, the English police were unable to do little more than contain its geographical spread. Restricted media coverage, with small segments of TV footage being repeated continuously on loops, also failed to prevent the spread of information over the internet as rioters used Twitter and a variety of online social networks to co-ordinate their actions. Government insistence that the disturbances were gang-related and not social discontent were dismissed by the international press and given little support by the subsequent Ministry of Justice breakdown of the social composition of arrested rioters.9 Harsh sentences followed.

While the potential for violence was continually present, and present on an international scale, events took a different and more non-violent turn in Spain. As in France and Greece, the focus of the protest was over austerity, and again online social networking sites played a crucial role. Spanish “indignants” used social networking sites to organize defiance of a temporary ban upon protests in Madrid. The regional and municipal elections were due and, until over, there were to be no large public mobilizations. All such mobilizations would be illegal. The ban proved ineffective, perhaps even provocative. The mass turnout on 15 May, the day of defiance, was the spark for protests which, according to Spain’s public broadcasting company Corporación de Radio y Televisión Española, involved more than 6.5 million Spaniards at some level or another.10 With national unemployment sitting above 20 per cent for adults and rising to double that figure for sections...