![]()

Chapter 1

A Lesson in Resilience: the 2011 Stanley Cup Riot

Garth S. Hunte

On June 15, 2011 a public disturbance broke out in down-town Vancouver, British Columbia, immediately following the seventh game loss of the Vancouver Canucks to the Boston Bruins in the National Hockey League Stanley Cup play-offs. Almost 9 million people in Canada watched the Stanley Cup final, making it one of the most viewed hockey games in the country, second only to the 2010 Olympic Gold Medal men’s hockey game between Canada and the United States. Several reviews have been conducted (two internal (City of Vancouver, 2011; Vancouver Police Department, 2011), and one external (Furlong and Keefe, 2011) to query how the riot happened, and how the police responded. In this chapter I review the response of the local hospital emergency department (ED) to the sudden surge of riot-related patients, and offer some observations about resilient system performance.

Spectator Violence

Spectator violence has existed since the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Riots involve crowds and violence in temporary social acts of collective behavior. Sports crowd violence emerges from the dynamic interplay between individual, interpersonal, situational and social factors (Spaaij, 2014). Many episodes of sports crowd disorder appear to be influenced by game-related factors, and are more likely to occur after championship games (Lewis, 2007; Jamieson and Orr, 2012). Riots occasionally erupt far from the site of the sports event. When the New York Rangers won against the Vancouver Canucks in the 1994 Stanley Cup, for example, a destructive riot broke out in the streets of Vancouver, 4,800 kilometers away.

Theories of disorder tend to focus on social injustice, inadequate institutions and the improper distribution of resources and political power. Riots are seen as a result of the failure of structures to accommodate demands and satisfy the expectations of certain groups. Perceived injustice, rather than actual deprivation, is seen as a principal cause of disorder.

In this event, the perceived injustice, whether it be loss of the game and the Stanley Cup and/or broader social issues, combined with alcohol and congestion to ignite the riot.

The Riot

An estimated 155,000 people were crowded into the down-town core of Vancouver, with many squeezed shoulder-to-shoulder into a two-block fan zone to watch the game on two large screen Live Site televisions at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Plaza (Furlong and Keefe, 2011). This set-up was similar to the successful public viewing of the men’s ice hockey gold medal game between the United States and Canada at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics.

The crush of people had been arriving on the down-town peninsula—500 people every 90 seconds by SkyTrain1 alone—by foot, road, bridge, ferry, and SeaBus2 over the course of the afternoon. Excited fans filled both large screen viewing areas to over capacity well before the puck dropped at 17:00.

Many were fuelled by excessive alcohol consumption—much of it consumed outside the down-town core prior to their arrival. Despite early closure (16:00) of down-town public and private retail outlets by the provincial Liquor Control and Licensing Branch (LCLB), fans were arriving drunk, an adaptive change, perhaps, from early closure of alcohol sales by the LCLB for game 5 two days before. A comparison of alcohol sales to those on the same day one year prior demonstrated a substantial increase in sales from outlets concentrated along public transportation corridors, and particularly so along the SkyTrain/Canada Line and SeaBus. Signs of trouble were already emerging at the Live Sites before the puck dropped.

The riot began to take shape as the game came to a close at 19:45, beginning with fisticuffs and bottle throwing, and progressing to overturning vehicles, setting them ablaze, smashing windows, vandalism, and looting. Many bystanders remained on scene to record the event on social media (Schneider and Trottier, 2013), which contributed to congestion and interfered with police and emergency personnel access. Police officers had switched from their award winning ‘meet and greet’ strategy to riot gear at around 20:00, and found the extreme congestion stifled riot prevention and then suppression.

Emergency Department Response

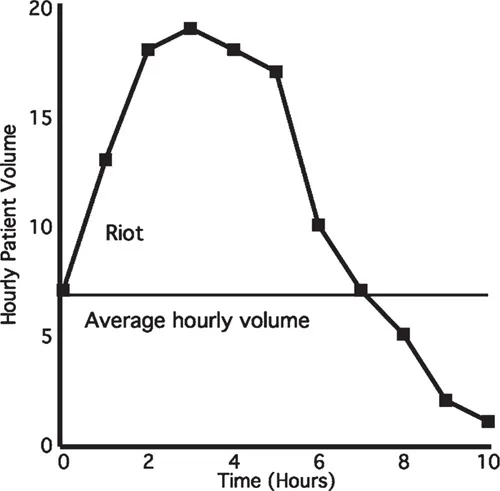

In all, 147 injured rioters and bystanders headed to the nearest Emergency Department (ED) at St Paul’s Hospital. Most arrived within a four-hour period at a rate of 18 patients per hour between 21:00 and 01:00, or about twice as many as the ED typically sees in a given night (mean hourly average for the same month-day of the week over the previous 5 years is 6.8). These were the busiest few hours the hospital has ever experienced. In the 12 hours between 19:00 on June 15 to 07:00 on June 16, 114 of the 144 patients seen (80 percent) at St Paul’s ED were there as a result of the riot. This number does not include the estimated 25 or more patients that were treated or hosed down at the First Aid station outside but were not registered.

Of the 114 riot-related patients seen (median age 27 years, 72 percent male), alcohol toxicity was documented in 43 cases and suspected but not documented in an additional 37 cases. For 13 patients, intoxication was the sole presenting complaint. However, the majority of riot-related patients (80 percent) registering at triage to see a physician, presented with mild to moderate trauma, including lacerations, burns, toxic exposure, fractures, and head injuries. Lacerations contributed the greatest proportion (49 percent) of injuries, and most patients were seen, treated, and discharged from the emergency department.

Figure 1.1 Patient volume over time

One patient had a traumatic pneumothorax requiring chest drainage, but was managed with an ambulatory flutter valve (a Heimlich valve) and discharged. Advanced imaging using computered tomography or ultrasound and/or surgical consultation (plastics, orthopedics, and urology) was required for 18 (16 percent) patients, but no riot-related patients required admission to hospital. Four patients left against medical advice, and two patients registered but left without being seen by a physician.

Emergency staff had been put on “Code Orange” (disaster plan) alert to prepare for mass casualties, but when the wounded, intoxicated, and tear-gassed patients began arriving, the ED got so busy that “Code Orange in Effect” was never called in the department. Nonetheless, emergency staff were able to make use of lessons learned from the 1994 Stanley Cup riot, and the training and preparations done ahead of the 2010 Winter Olympics, when all hospitals across Vancouver had spent months working with police and other first responders about how they would coordinate in the event of a terror attack or other disaster.

A contingent of nurses trained in Hazardous Substance Response was assigned to run a pre-arranged decontamination station outside the ED for tear-gas injuries. They set out garbage bins filled with water so people could dunk their heads to relieve the burning from the gas. The injured were then partially stripped and hosed down to remove the tear-gas powder. By keeping the tear-gas injuries outside, staff ensured the ED itself was never contaminated with the powder. Other staff operated a triage station in a courtyard outside the ED to treat those with minor injuries, such as cuts and scrapes. None of these patients were registered in the ED.

Patients presenting with more serious complaints, such as stab wounds, head injuries, and broken bones, were triaged in the usual manner to be seen by an emergency physician.

Dozens of nurses, physicians, residents, and other hospital employees who came in to help, even if they were not on duty, mitigated the pressure of the sudden volume of patients. Additional off duty and off service physicians and residents, administrators, and technicians who had been watching the game and had witnessed the riot unfold came in to pitch in and help in any way. Even patients were helping other patients.

In the words of one emergency physician:

I want to thank everyone for doing a spectacular job, the physicians who just came in, or called to ask if they were needed, the nursing staff who ensured everyone was treated with dignity, the technical and security staff for helping in ways that went beyond their duties, the clerical staff for keeping up and making sure no one was overlooked, the supporting and consulting medical services who were incredibly responsive, and the administrator who came to help because it was the right thing to do.

Although the hospital emergency response system worked according to plan, the additional help of providers who showed up and filled the gaps allowed the department to cope and recover. By 01:20, “Code Orange” was cancelled, and the ED was back to normal.

Resilient System Performance

This fortuitous case exemplifies the cornerstone capabilities of resilience (Hollnagel, 2009a) through learning (the 1994 Stanley Cup riot in Vancouver), anticipation (disaster preparation for the 2010 Winter Olympics), monitoring (television and media coverage), and response (beyond the formal plan) and offers implications for the design of resilient systems. It demonstrates that system performance under constraints (ambiguity, uncertainty, time pressure, risk, and so on) is “not constituted of parts and their interactions, but as a web of dynamic, evolving relationships and transactions” (Dekker, 2005, p. 2).

Overload is a common stressor, and has been implicated in the catastrophic collapse of complex systems in multiple domains (Weick, 1990; Rudolph and Repenning, 2002). The sine qua non of an emergency department is timely response to acute illness or injury, which requires the capability to take on new work. However, as work increases, the mismatch between demand and capacity also increases, and contributes to prolonged length of stay and crowding. This “falling behind the tempo of operations” is a classic pattern of decompensation (Woods and Branlat, 2011a), and is a daily pattern in an urban ED. The diurnal pattern of work (Welch, Jones and Allen, 2007) is also a recurring pattern in an ED, and the overnight nadir may function as a form of recovery (Wears, 2011a).

When possible, workers in human-paced service systems attempt to accelerate the system under high-load condition through task-load reduction or early-task initiation, a phenomenon called Speedup (Batt and Terwiesch, 2012). An ED is interesting because it is also a complex service environment with many shared resources (nurses, doctors, equipment, hallways, laboratory, and so on), which suggests it is also prone to Slowdown. System throughput decay caused by sharing is a function of both load on the system and the proportion of service that requires use of shared resources.

An adaptive system is able to cope effectively up to a point (elastic region), gradually starts to fall behind (plastic region), then abruptly slows (fracture or deformation) (Woods and Wreathall, 2008). In a resilient model, large increases in work processed contribute to only small increases in recovery (Wears, 2011a), and the system is able to keep pace. Exploitation of resources (for example, additional staff) to enhance the margin for maneuver (Stephens, 2010), contributes to improvements in performance by mitigating the disruption, shortening the time to recovery, and increasing the threshold for decompensation.

In this instance, there were several factors that contributed to successful system performance.

• Experience: the hospital had experience with a similar riot, albeit 17 years earlier, but this informed the decontamination and first aid stations that deflected a portion of the patients presenting (minor injuries) and reduced the intake at triage.

• Practice: there had been practice with the training and preparations done ahead of the 2010 Winter Olympics, which informed the hospital emergency response system and the charge nurse’s personal planning for that night.

• Anticipation: the riot was a possibility in more than words and ideas, particularly for nursing and physician clinical leaders. The vulnerability was anticipated and resources were pre-emptively increased.

• Resources or margin: there was ample help, people stepped up, but there was no “all hands on deck.” In addition, supporting services like radiology and surgical specialities were responsive, and the infrastructure of the system was intact. This would be unlikely to be the same in a natural disaster such as an earthquake.

• Throughput: the surge of patients was not sustained, nor did many of their injuries require intensive resources or prolonged stays in the ED. This contributed to timely discharge.

• Timing: the surge happened late in the evening and overlapped with a regularly occurring low point in patient volume.

• A typical societal adaptation: finally, fewer non riot-related patients presented than usual, presumably staying away because of the riot.

Thus, work in progress was able to be completed before new work increased, which did not leave the system in a degraded state for more than a few hours.

Learning

The potential for a public disturbance and increase in ED patient volume was anticipated and planned for, and providers and leaders are understandably proud of what they accomplished in an acute crisis overload. This highlights the strategic position of an ED within a health care system as the interface between community and acute care, and emphasizes the need for anticipation and monitoring of mass-gathering events, with effective and timely communication and coordination between emergency services and the ED.

There has, unfortunately, been limited organizational learning. Although there has been discussion and testing of provider call-out using text messaging, and the possibility discussed of regional accreditation so that providers can assist at other health care facilities in event of a disaster, there has, for example, been no update of the formal ED Code Orange plan since 2006. Greater coordination, communication, and practice between Emergency Preparedness and the ED will afford a more nimble and adaptive response.

Moreover, the chronic everyday overload of ED crowding has been unaffected by this experience, in part because everyday congestion has become “normal.” This leaves unanswered the question of whether or not the ED will be able to cope effectively again in the future, and particularly if the situation is less advantageous with respect to timing and throughput as might be anticipated in event of a disaster such as a major earthquake.

Violence will continue to be associated with the staging of spectator sports. The dominant response of societies to date has been physical control tactics backed by force or legislation (for example, availability of alcohol), educating the public through media messages, and programs targeting spectator groups. Empirically based tactics that can limit the incidence and scale of spectator violence are scarce.

Summary

In summary, the riot was a test of the department’s performance under stress, but it was brief and limited. The collective joint action of pre-hospital/hospital providers, staff, ancillary services, police, and the public allowed the ED system to keep pace and not fall behind. The margin was increased pre-emptively, but additional marginal increases that went beyond the formal plan emerged spontaneously to match the actual situation. Alas, the chronic overload of everyday work in a complex system has not garnered the same learning, anticipation, monitoring, and response.

![]()

Chapter 2

Translating Tensions into Safe Practices Through Dynamic Trade-offs: the Secret Second Handover

Mark A. Sujan, Peter Spurgeon and Matthew W. Cooke

Introduction

Failures in the handover of responsibility for patient care from one caregiver to another are a recognised threat to patient safety (Cohen and Hilligoss, 2010; Raduma-Tomas et al., 2011). Handover in emergency care comes in different shapes and forms. For example, at the end of a shift there is a handover between the outgoing physician and the incoming party. This type of handover takes place between individuals of the same discipline and professional background. In addition, there are other types of handover that take place along the patient pathway. For example, ambulance crews hand over to emergency department (ED) staff. At the other end of the patient pathway in emergency care there are handovers from ED staff to in-patient hospital services. The study presented in this chapter focused on these types of handover along the patient pathway, because they involve individuals fro...