![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Justice

KATHRYN SLANSKI

In order that the mighty not wrong the weak,

to provide just ways for the orphan and widow,

in Babylon—city that the gods Anu and Enlil have elevated,

in Esagila—temple whose foundations are fixed as are heaven and earth:

to judge the judgments of the land,

to decide the decisions of the land,

to provide just ways for the wronged,

I inscribed my precious words upon my stela

and set it up in the presence of my image, the just king.1

—Law Stele of Hammurabi, King of Babylon (xlvii 59–78)

INVESTIGATING JUSTICE IN ANTIQUITY: CHALLENGES, APPROACH, SOURCES

Justice in the ancient world is notoriously difficult to pin down. Plato’s Republic (Politeia, literally, “Of the Polis”), perhaps the most familiar and culturally influential of the fifth century Athenian philosopher’s dialogs, had in antiquity already acquired the subtitle: Dikaiosune “Concerning Justice.” At the work’s center are the joint inquiries: “What is justice?” and “Is its value instrumental or for its own sake?” Yet, like the young men participating in the discussion led by Socrates, students of the Republic today seeking “the answer” or even “an answer” to those questions are left frustrated and unsatisfied. Is justice “giving what is one’s due?” “Helping friends and harming enemies?” “Each doing his own job?” By the time Socrates has described a transmigration of souls through the parable of Ur in the Republic’s tenth and concluding book, each of these proposals has been considered and rejected. Taken singly or even together, they fail to capture what any reader, ancient or modern, would consider the full meaning and value of justice.

A quick survey of the very words most commonly rendered in English as “justice” hint at the complexity with which the ancient world approached the idea. For ancient Mesopotamia, which bequeathed us the earliest evidence for our engagement with the subject, the usual Akkadian word for “justice” is misharu. In the last line of the passage cited above, Hammurabi refers to himself as shar mishari “king of justice,” that is, “just king.” Etymologically, misharu means “something made straight,” and implies, then, restoration to a previous state that had become “crooked” or “out of line.” In Akkadian inscriptions, misharu is regularly written with its Sumerian language equivalent, NÍG.SI.SÁ, literally, “thing made straight,” which likewise implies a restoration to a prior—and more just—condition.

Akkadian kittu “truth” is often paired with misharu; taken together they describe “two facets” of justice: the upholding of traditional law (kittum, “truth”) and the tempering of the “harsh letter of the law with equity (misharu, ‘justice’)” (Westbrook 2003b: 364). Both words sometimes appear deified, thus “the god truth” and “the god justice”—suggesting a dimension of agency not easily transposed to the twenty-first century.

In the Hebrew Bible, tsedeq usually translated by “justice” or “righteousness,” also connotes “normal” or “normative,” while mishpat, also translated “justice,” refers more specifically to “judgment,” “ordinance” and “right” or “rectitude.” Tsedeq may be understood as primary “justice,” maintaining correct relationships with God and others, that results in a right life, in contrast to mishpat “rectifying justice,” that is, “punishing wrongdoers and caring for victims of wrongdoing”2—a distinction that echoes Hammurabi’s commitment to prevent the strong from wronging the weak, to providing “just ways for the widow and the orphan.”

In ancient Greek, the term usually rendered as “justice” is dike, also conceptualized as a divinity. Mythologically, the goddess Dike—together with her sisters: Eunomia (“right laws”), Eirene (“peace”), and the four seasons—was born of a union between Olympian Zeus and the titan Themis, whose name means “right.” According to Hesiod’s Theogony:

Next he [Zeus] married gleaming Themis, who bore the Seasons,

And Eunomia, Dike, and blooming Eirene,

Who attend to mortal men’s works for them … (906–908)

Greek dike circumscribes even more meanings than Akkadian misharu, and could connote revenge, a trial, or legal action, as well as an abstract notion of justice. While English translations render dike differently according to specific contexts, all these interrelated meanings would have been relevant for an ancient audience.3

This chapter draws on a selection of written works from two cultural traditions that exemplify some of the most prevalent, provocative, and enduring ancient ideas about justice: the cuneiform tradition of the ancient Near East and the Greek tradition of the ancient Mediterranean. It would be impossible to treat comprehensively all the works from antiquity that deal with justice, and in order to achieve some depth over superficiality, the works considered in this chapter address core questions or problems of justice in ways that have had lasting impact, and that were aimed at broad—in some cases explicitly public—audiences in antiquity. These are also works that we know to have been studied in antiquity, to have belonged, to greater and lesser degrees, to the body of written texts that formed the curricula of ancient education in their respective regions. Consequently, these are works that played a role in the intellectual formation of educated individuals who went on to become bureaucrats, magistrates, judges, court advisors, rulers, and, of course, writers who authored subsequent works.

Inquiry into the cultural ramifications of justice in ancient Mesopotamia and ancient Greece yields a number of points that the chapter will explore in closer examination of selected works of literature and art. These are:

• that in antiquity, justice is—and must be—continually debated and evaluated, and scenes of discussion and debate are characteristic of presentations of justice in ancient literary works;

• that visual imagery used to convey the execution and maintenance of justice make use of instruments to enable accurate perception; these include symbols for weighing and for measuring, for separating truth from falsehood/relevant from irrelevant, and for illumination and vision (as opposed to opacity and blindness);

• that for both the ancient Near East and Greece, justice vs injustice is commonly expressed as “straight” vs “crooked,” a structural conceptualization also manifest in the idea of a divinely ordered universe;

• that justice originates fundamentally with the gods, and is manifest in the gods’ creation and ordering of the universe, evidenced in creation myths;

• that, consequently, justice is inherent in the very structure of the universe, for example, the Greek concept of kosmos (see below);

• that the divinely ordered structure of the universe includes a hierarchy in which man is subordinate to the divine, and, consequently, man can only ever have an imperfect and incomplete, that is, non-divine knowledge of justice (this is made clearer in the ancient Near East than in the Greek-speaking world);

• that in ancient Near Eastern mythology, man’s trespassing on the divine realm results in a re-creation followed by a re-calibration of the cosmic hierarchy, one that firmly re-establishes man’s station subordinate to the divine;

• that in the Greek-speaking world, we see man’s challenges to the divine executed on a smaller, individual scale. Such challenges are rectified by the gods, again, with an idea of re-establishing the (necessarily prior) just order; and

• that rulers are responsible—charged by the gods—with maintaining and restoring just order in human society, analogous to the gods’ doing so on a cosmic scale.

This chapter considers a selection of some of the best-known and best-attested works of ancient Near Eastern and Greek literature, those that would have formed part of the cultural background shaping the assumptions and values behind legal processes. In addition to the classical world, our Western tradition of justice also has roots in the ancient Near East, whose approaches to law and justice come down to us chiefly through the Bible.4 Like the classical tradition, the Near Eastern tradition emphasizes a divine origin for justice, and a divine mandate charging rulers—the state—with the obligation to execute and maintain lasting just ways for their people.

The chapter takes as its starting point an explication of the way justice is portrayed by Law Stele of Hammurabi, popularly known as the Code of Hammurabi, our earliest surviving monumental source for the cultural history of justice. From ancient Greece, the chapter will explore justice in works that achieved panhellenic status during the archaic period, those that, in contrast to local myths and traditions, were known widely throughout the Greek-speaking world. Works considered include Hesiod’s Works and Days, with reference to scenes from Homeric epic. From the fifth century “classical” or “golden age” of Athens, the chapter takes a close look at Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy before concluding with the Melian Dialogue from Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian Wars.

Utilizing both verbal and visual expression, Hammurabi’s Stele evokes an element of performance, which, along with other works surveyed in this chapter, suggests that in both the Near East and the classical world, justice is regularly expressed through some type of performance before an audience, be it dialog, debate, disputation, or a formal theatrical performance upon a stage. Together with its very resistance to easy definition, the element of performance suggests that in antiquity justice was regarded as neither “fixed” nor “fixable,” and rather as productively and necessarily a subject for discussion and debate.

LAYING SOCIAL FOUNDATIONS FOR JUSTICE: THE LAW STELE OF HAMMURABI

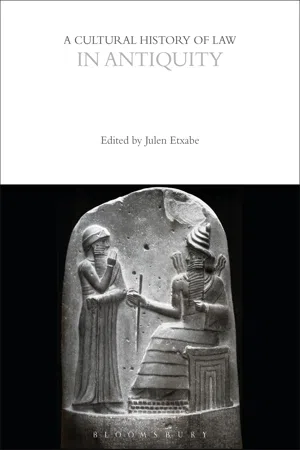

Hammurabi’s5 almost complete stele, housed today in the Louvre, stands 2¼ meters tall, some 70 centimeters wide. The inscription is partnered by a compelling sculpture in low relief that crowns the 2-meter high stone monument. Descriptive rather than prescriptive, the Stele is not, properly speaking, a code, and is more readily classified today as an example of the ancient Near Eastern genre of royal inscriptions called “law collections.” Of the several cuneiform law collections known to us, Hammurabi's inscription is the longest and most developed. The inscription of the Law Stele of Hammurabi is not the earliest law collection from ancient Mesopotamia, but, without a doubt, it is the best known and most studied.6

There is strong evidence that King Hammurabi was personally and intensively invested in the adjudication of legal disputes throughout his realm. He conducted extensive correspondence with officials and judges throughout his kingdom, keeping informed and offering opinions on a wide range of judicial proceedings, at times ratifying and at times questioning decisions by “lower” judges. Many of these letters from the king have survived, and they suggest that actual law cases and judgments executed during Hammurabi’s reign, together with theoretically driven expansions of such cases, may have been the primary sources for the legal decisions, the so-called “laws” assembled and inscribed on his monumental Stele. Thus, while not a law “code” in the sense of proscribing laws in a comprehensive and systematic fashion, the decisions collected and preserved on the stele do represent the legal rules and prescriptions established by a sovereign authority. Although very few actual trial records refer to the stele, the consensus among scholars is that the decisions inscribed “do not conflict with legal practice as evidenced in actual contracts from everyday life” (Greengus 1995: 472).7

The Louvre stele was most likely originally erected in the Esagila, the temple of the god Marduk in Hammurabi’s capital city of Babylon, or possibly in the Ebabbar, temple of the god Shamash in the city of Sippar. A French expedition discovered Hammurabi’s Stele in excavations undertaken in 1901–02, not in Babylon or Sippar but in Susa, the capital city of Elam, a rival power to the east, where it had been taken and displayed by a twelfth-century Elamite king.8 Additional stone fragments found at Susa suggest ...