![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Jesus Did Not Wear a Turban: Orientalism, the Jews, and Christian Art

IVAN DAVIDSON KALMAR

The Old and the New Testaments are the Great Code of Art.

—WILLIAM BLAKE

In Christian art, it is a common practice to represent biblical Jews as if they were Muslims. Perhaps the most striking examples are some of the works of Rembrandt van Rijn. In David and Uriah, for instance, the two men’s Ottoman-style turbans play a dominant part in the composition (fig. 1). Later, in the nineteenth century, it became more common to imagine biblical Israelites wearing not the Turkish turban but the Arab headscarf or kaffiyeh.

American popular culture has continued to quote this tradition. When we see the kaffiyeh on the heads of the Israelites led to the Promised Land by Charlton Heston, we are not surprised. In The Ten Commandments Hollywood builds on an artistic practice established during the previous five centuries and more. The Jews of Europe and North America have themselves accepted this pictorial language. Modern illustrators of Passover Haggadot often show the Children of Israel tending their flock in flowing robes and kaffiyeh, looking very much like traditional Palestinians.1 It is, of course, possible that the ancient Israelites dressed somewhat like Palestinians or even Ottoman Turks. Nevertheless, it is clear that artists, with important modern exceptions, have not based their representations on archaeological research in the Holy Land, but on contemporary images of the Muslim world. The history of Western thought about the Orient, rather than the facts of biblical couture, must therefore be our primary subject here: a history not of “oriental” costume but of the orientalist representation of the biblical Jew.

As a subject of research such representation has little history.2 In general, recent analyses of orientalist art have ranged from Linda Nochlin’s treatment of it as a “picturesque” religious ethnography of Islam in a colonial context (she pays no attention to orientalism in biblical representation) to Malcolm Warner’s suggestion that “the issue at stake in the portrayal of Islam in nineteenth-century art was not Islam at all, but Christianity.”3 Both scholars’ analyses deal almost exclusively with the nineteenth-century art movement known as “orientalism.” I would like to show that orientalist representations of the Bible have even longer roots.

FIG. 1. Rembrandt van Rijn, Biblical Scene with Two Figures [David and Uriah?], oil, 127 × 117 cm, Hermitage, Saint Petersburg (photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York)

The matter is of much more than antiquarian interest. The portrayal of biblical Israelites was not a marginal aspect of the orientalist imagination. On the contrary, it was a major arena where the nature of the Western image of the East as a radically different Other, opposed to the West, was first disclosed.

The parallel representation of Jew and Muslim in art, as in orientalism in general, underwent a number of major discontinuities, while maintaining a certain overall continuity. Changes in the use of Muslim attire to depict the Jew in Christian art have been symptomatic of the different stages of Western representations of the Orient (discussed in the introduction to this volume) from the conquest of Constantinople by the Muslims to the conquest of Muslim lands by European colonizers. What did not change was the representation of Jesus in contrast to his Jewish environment, in accordance with the fundamentals of Christian theology. The New Testament, in the authoritative Christian view, is rooted in yet surpasses and in that sense opposes the Old. Accordingly Christian art constructs a Jesus who is born Jewish but whose nature surpasses the limitations of Judaism. Challenged only in the modern period by a few Jewish artists bent on creating what in another context Susannah Heschel has labeled the “Jewish Jesus,”4 the Jesus of Christian art over the centuries has been essentially a non-Jewish one. In the type of Christian art discussed here, the contrast between Jesus and his people is put in orientalist terms: Jesus, and with him by implication the Christian West, rise above their spiritual origins in the Jewish East. The essence of religious orientalism is revealed by the fact that, in Christian art, most Israelites can typically be shown as Muslims, but not Jesus Christ.

The History of Biblical Headwear

The Jews of the Bible came to be represented as orientals as soon as the Muslims did.

Until the fifteenth century the most serious Muslim threat to the Christian West came from the South and Southwest, not the East. And the East was not necessarily imagined as Muslim. In the early and High Middle Ages, the “East” and “Orient” referred to, in Western parlance, primarily to the Roman Empire in the East, to Byzantium, the Christian dominions of what was referred to in Western languages as the “oriental church.”5 Although oriental Christians were regarded as somewhat exotic, there is no reason to think that they were represented as in any way similar to Muslims or Jews; at least not until the fifteenth century when, it is true, there are some indications that the oriental Christian look was sometimes, so to speak, Islamized. One of the most striking examples is found in the Limbourg Brothers’ illuminated manuscript, the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (1413–16). The Emperor in The Virgin, the Sibyl, and the Emperor Augustus (folio 22 reverse) wears a long white beard, a diademed “Persian” hat, and a curved sword, all of them signs of the Muslim Orient. The figure is believed to be inspired by Manuel II Paleologus, the Byzantine emperor who traveled to Rome, Paris, and London between 1399 and 1402, hoping in vain to drum up support for his struggle with the Ottomans. The same character reappears as the magus of the East in the Meeting of the Magi (folio 51 verso).

Manuel and his retinue were the subject of intense curiosity in Western Europe, fascinating their hosts with, among other things, their exotic attire. In Benozzo Gozzoli’s frescoes at the chapel of the Medici-Riccardi Palace in Florence (1460), Manuel is believed once again to have provided the model for the Magus of the East. Benozzo, too, depicted him wearing the “Persian” hat, also used in portraying Jews. Such exoticization of the Eastern Christians was symptomatic of the extent to which the West was beginning to write off the Orient. It bode ill for Manuel, who came to Italy in a desperate attempt to save his empire from the Muslims, pleading the common heritage of Rome and Constantinople. His efforts were in vain: his undertaking to unite the Western and Eastern churches failed to excite enthusiasm either among the Orthodox clergy (who rejected it) or in the West.

Depicting Manuel in terms evocative of Jews and Muslims was not indicative of any medieval tradition that conceived of an alien Orient including not only Muslims and Jews but also eastern Christians. Rather, the “orientalization” of the Christian Orient betrayed an entirely new state of affairs that Manuel, to his detriment, failed to understand. The “East” had for the first time come to be imagined as lost to Christian rule, and as marked by the alien ways of the Muslim. In other words, the Islamization of the image of the emperor of the East is symptomatic of the rise of orientalism, in the same way as the Islamization of biblical images (though in considerably less obvious ways; for example, the Byzantine emperor, unlike the Eastern king in Adoration scenes, does not wear a turban). The change of perception was forced on the West by the military successes of the Ottomans, crowned by their conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

Only now was it possible to picture the biblical story in an exotic setting modeled on the contemporary Muslim, and specifically Ottoman, East. The biblical lands, now indelibly in Ottoman hands, came to be exoticized in the Western imagination as part of the Orient as a region with a religion. The inhabitants of biblical and contemporary Palestine were both visualized in the Renaissance (and for a while later) on the pattern of the “Turk.”

Pre-orientalism

Nabil I. Matar showed how the turban was the main visual marker of Islam in the European Renaissance, eclipsing in importance the crescent and the scimitar.6 That is not to say that the Ottoman turban was the first artistic device that equated Muslim and Jew. Earlier Christian portrayals of both, though less exoticizing, did equate these two religious Others. Some particularly literary examples are examined, in this volume, by Suzanne Conklin Akbari. Another telling instance that has, to my knowledge, not previously been reported is from the famous Parzival by Wolfram of Eschenbach (who died sometime about 1230). Parzival’s father, Gahmuret, leaves for the East, not as a crusader or a hostage, but voluntarily to enter the service of a personality that Wolfram thinks of as the spiritual leader, a kind of pope of the Muslims, resident at Baldac (presumed by modern critics to be the city of Baghdad). The better-known manuscripts describe this leader as bâruc, which is a title or name that has not been attested at all independently and seems to make no sense.7 Maxime Rodinson suggests that it is a corruption of mubârak, Arabic for “blessed.”8 It might make more sense to read it as baruch, or Hebrew for the same thing. Indeed, the manuscript owned by the Munich library9 does have barruch rather than bâruc. The Hebrew term for “blessed” is very common in the Jewish liturgy, so that anyone with minimal familiarity with Hebrew might conceivably have used it.

During the earlier Middle Ages, biblical Jews were often portrayed wearing various kinds of so-called Jewish hats. A yellow conical hat was perhaps the most common. Another type was a wide-brimmed hat culminating in a small ball on a short stem. The painterly practice here corresponded, of course, to actual medieval custom: in the Middle Ages Jews wore distinctive headwear as well as other elements of clothing, often as a result of papal or princely decree. In some cases the depiction of the “Jewish hats,” though modeled on what European Jews wore, may at the same time represent a link to the East. The “Persian hat” shown on Manuel II was typical Jewish headwear, and appears in the Encyclopaedia Judaica with the caption, “France, 13th cent.”10 Yet it appears as well in Muslim miniatures from Iran and India. Perhaps it is indeed of Persian origin, and somehow found its way to Europe, possibly carried by Jews who came from the Byzantine Empire.

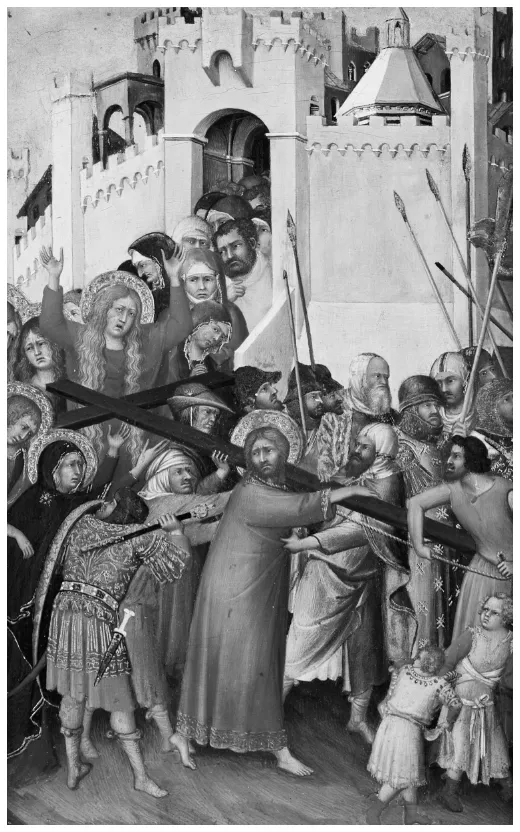

Another common style of “Jewish” headwear is only a little less obscure. It appears to have completely escaped the attention of art historians that, particularly in Italy, biblical Jews were often shown wearing a white headscarf wrapped around the head and neck. A thirteenth-century example is Duccio di Boninsegna’s altarpiece Maestà (1308–11) in the Siena Cathedral museum. From the fourteenth century one might cite Simone Martini’s Passion (or Orsini) polyptych (1333). In the “Road to Calvary” panel, now at the Louvre, a number of personages wear the headscarf in question. The scarf on the head of one of the Jews on Jesus’ left is particularly interesting in that it includes several dark stripes (fig. 2). It may well represent the Jewish prayer shawl or tallith (which is normally wrapped around the shoulders, but may also be used to cover the head). That, at any rate, is the opinion of one art historian regarding similar headwear seen on biblical Jews in Byzantine art. If she is right, then we can identify the hood, both its striped and its plain variety, as an iconographic convention stemming from Byzantine depictions of the tallith.11 Alternatively, the headscarf might not be of Jewish origin at all. It does resemble a type of headwear that is worn to this day by traditional North Africans, a white hood that protects both the head and the neck. At any rate, regardless of whether its origins are Jewish or Muslim, the headscarf is shown by Christian artists on both. For example, in the late thirteenth-century painting Saint Clare Driving Back a Saracen Attack (fig. 3), attributed to Guido da Siena, the headscarves worn by the Saracens are practically identical to those worn by Duccio’s or Simone Martini’s Jews.

FIG. 2. Simone Martini, Christ Bearing the Cross, 1325–35, panel from the “Orsini (Passion) Polyptych,” tempera on wood, 25 × 16 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris (photo: Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York)

FIG. 3. Guido da Siena (or follower), Saint Clare Driving Back a Saracen Attack, c. 1250–1300, detail from the Diptych of Saint Clare, oil on wood, 123 × 72 cm, Pinoteca Nazionale Siena (photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York)

If it is true that the model for the headscarf is Muslim—something that at this stage must remain at the level of speculation—then we can conclude that in the thirteenth century the pictorial identification of Jew and Muslim was already on its way. If so, then the headscarf rather than the turban announces the Islamization of the Holy Land in the Western Christian imagination, and the development needs to be located in the thirteenth century. The date would not be surprising. In 1187 Salah ud-Din (Saladin) reconquered Jerusalem and after that, with the brief interludes of 1229–39 and 1243–44, the city was to remain in Muslim hands until the twentieth century. Though Crusader rhetoric raged for a few hundred years more, Christian art betrays that Europeans slowly began to give up the idea of a Christian Jerusalem.12

Turbans

If we can conjecture that the “orientalization of the Orient” began in the thirteenth century, we can be quite certain of it in the fifteenth, when the practice of depicting Jews in turbans became firmly established. Before the late 1400s, one only rarely sees a biblical Israelite depicted with a turban. One exception is the twelfth-century (after 1187) bronze door of the Cathedral of Pisa by Bonanno (the architect of the “Leaning Tower.”) Bonanno shows some prophets protected by the shade of palm trees, probably meant to index the oriental environment. These figures wear what look very much like turbans. Such depiction was, however, very rare. Even the early fourteenth-century work of Giotto avoids orientalizing the biblical Jew. He was familiar with the turban, and did place it on the head of the “Sultan” in his 1325 Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis, the famous fresco in the Bardi Chapel ...

![Image: FIG. 1. Rembrandt van Rijn, Biblical Scene with Two Figures [David and Uriah?], oil, 127 × 117 cm, Hermitage, Saint Petersburg (photo: Scala/Art Resource, New York)](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/2236608/images/ch1f1-plgo-compressed.webp)