![]()

CHAPTER 1

The African American Experience in Cabell County, Virginia / West Virginia, 1825–1870

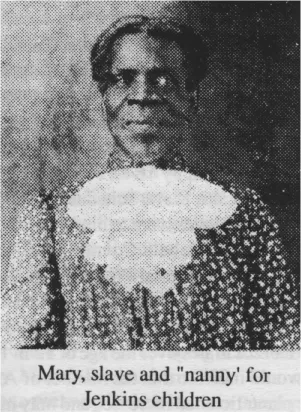

In 1865 former slave Mary Lacy faced a range of choices. At the end of the Civil War, after a lifetime of service to various members of the influential Jenkins family of Cabell County, she was free but uncertain. After surviving the nearly quarter-century reign of family patriarch Captain William Jenkins, who in 1825 purchased the immense Greenbottom Plantation from William A. Cabell, former governor of Virginia, and assumed ownership of her and approximately two dozen other slaves, she was free. She had survived rape by the lecherous overseer Jenkins hired that had produced George, her son who was now ten years old. She had also survived the five-year rule of Jenkins’s son, Confederate Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins. It was he who, upon the death of his father in 1859, had inherited Mary and her son. Now, having suffered a mortal wound at the Battle of Cloyd’s Mountain, Albert Jenkins lay cold in the earth. Now, at age thirty and a single mother, she, along with the remaining residential slave population of Greenbottom, faced the very real prospect of leaving their home, her home since birth, and never looking back.

Figure 1.1. Mary Lacy, slave and caretaker for the children of Captain William A. and Thomas Jenkins, Cabell County, Va./W.V. Source: Jenkins Family Collection, courtesy of Victor “Jenkins” Wilson.

But history lay heavily upon her, a weight that could not be lifted by decree, victory, or freedom. Thirty years …

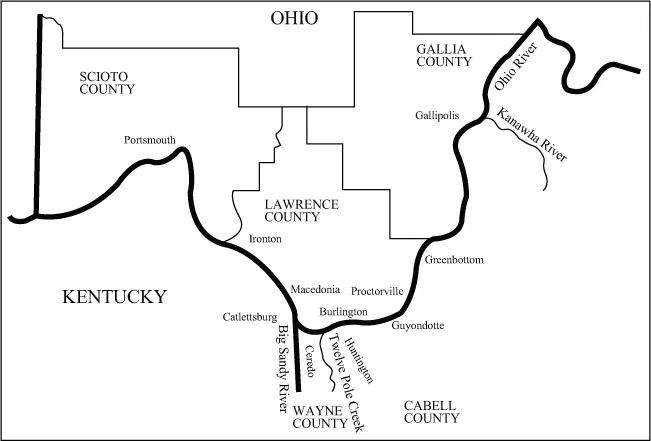

Over the years she had seen the increasing influx of slaveholders drawn by the county’s cheap, arable land and strategic location adjacent to the Ohio River near the tri-state area that included southeastern Ohio and eastern Kentucky (see map 1.1). She had also seen their slaves, most of whom accompanied their masters to the dozens of small farms that dotted the region. Unlike Kanawha County, Virginia, to the immediate northeast, from which Cabell County was formed in 1809, it lacked a foundation of industrial slavery. Unlike Jefferson County in the far northeastern panhandle, it lacked the numbers to support plantation slavery. Thus, Cabell County’s residential slaves suffered the cruel paradox of slavery: the loneliness attendant to social and geographic isolation as well as the forced dependence and incapacity foundational to the personal relationship between the master and slave. In many cases, slaves separated by miles from the next slave-owning farm and thus unable to associate with other slaves developed attachments with the master’s family and, in effect, became members of that family. This was the conundrum Mary grappled with.

She had also seen the growth of Guyandotte, the town formed in 1810 downriver from Greenbottom at the confluence of the Guyandotte and Ohio Rivers. By the mid-1850s both Guyandotte and Barboursville, the county seat formed in 1813, were vibrant villages that linked the rural, undeveloped backcounties that comprised two-thirds of preindustrial West Virginia to Cabell County and, from there, to the regional and national marketplace. Over the course of her years, she had seen how important slave labor was to this process. Both towns were beneficiaries of increasing river commerce and travel and the construction of a road that connected Guyandotte with the James River and Kanawha Turnpike at Barboursville. The turnpike’s importance as an east-west artery for all manner of travel and commerce was second only in use to the National Road and was a conduit for the transportation of slaves to the Deep South. Occasionally, black migrants had traveled the road to safety. In its sometimes difficult westerly course, it intersected and interconnected seven counties in the Virginia piedmont and four in West Virginia before encountering the eastern edge of Cabell County. At that point, the county was as far removed from Richmond and the Tidewater region of Virginia as any county in the state. Perhaps this would be the road she would take to start life anew.

Map 1.1. Ohio River Underground Railroad stations in tri-state area. Source: “Underground Railroad Tri-State Area,” tour brochure, Morrow Library, Special Collections, Marshall University, Huntington, W.V., 1.

More than anything, though, Mary had seen life at Greenbottom Plantation. Located adjacent to the Ohio River near the Mason County border, the plantation, home to more than 50 slaves in 1850, represented the least common form of slavery in the area and was the “social and economic centerpiece of the region.” It was also the locus of a historic presence of slaves possessing rudimentary literacy, which, at least through the mid-1800s, shaped the contours of social relations and power dynamics of the slave-master relationship within the county and, to some extent, within the region. As early as 1813, members of the slave community as well as the Greenbottom overseer knew that D’lea, a young female slave, possessed reading and rudimentary factoring skills, skills the overseer sometimes begrudgingly utilized. D’lea’s abilities and her master’s “unhappy dependence” on her reveal the complex interrelationship between slavery, spoken language, and functional literacy that existed in Cabell County and on the postrevolutionary western Virginia frontier. The diversity of land, disorganized task delegation, dispersed population, lax and irregular supervision, and class and age variance of white laboring partners gave rise to a reluctant “multicultural” sharing of reading, writing, and factoring. To help keep plantation records, a few of the slaves were trained to write, a skill that spread to other slaves during the unsupervised periods. Before long, many of the Greenbottom slaves could read and write and do simple math, a worrisome development for many slave owners. Educated slaves were a threat to order, individually and collectively, because they were capable of communicating with other slaves to participate in surreptitious behavior, including escapes. In fact, by the late 1810s, slaves were escaping from the plantation with passes they had written for themselves. Thus, as Marilyn Davis-DeEulis contends, “by the time William Jenkins and tanner John Hannah purchased Governor Cabell’s land and many of his slaves in September 1825, they were buying into several generations of ‘occupational literacy’ forged in very confusing circumstances that were backbreaking, ruthless, yet often collaborative.”

While it is unclear as to what extent slave literacy impacted slave-labor relations for the betterment of the slave, it is difficult to believe that it did not shape, if only for a time, the movement and use of slaves through sale, importation, inheritance, or hire that increasingly became common practice within the county. Slaves were frequently rented out for labor in the county in addition to the labor they performed for the master. Naturally, slaves also had no say in their sale, transfer, or purchase. In effect, whatever the nature of personal relationships between the master and slave in the county’s yeoman-based economy, it was not enough to overcome the recognition that the slave was seen as a unit of labor and vehicle of profit. Mary knew this reality all too well. Upon his death in 1859, William Jenkins bequeathed “Mary and her issue” to his son Albert and instructed that slave Jacob be sold to the highest bidder among his three sons. Jenkins further stipulated “slave Mary and her sire to be similarly disposed of at the death of his sister.”

Intrinsic to the maintenance of the slaves’ inferior status and abiding liquidity was the implied and/or actual threat or application of deprivation and violence. Notably, in its formative years Cabell County was what Ira Berlin labeled a “society with slaves”—a society in which slaves were never central to the economy or social structure. This distinguished the county from the rice- and cotton-growing regions of the deeper south—“slave societies”—where the political economy was inextricably woven into the fabric of the institution, and “the master-slave relationship provided the model for all social relations.” To what extent this dynamic contributed to or eased tension within the county, the harshest aspects of slavery associated with the Deep South are unknowable. What is known is that life on the plantation proved deadly for many, especially in its early years; that by the time of the Civil War, many of Greenbottom’s slaves had endured life on the plantation for nearly half a century; and that Mary’s son had been produced through violence.

Undeniably, this last fact must have complicated Mary’s decision-making process on whether or not to leave Greenbottom. She could decide to leave, to proceed down the unexplored paths of future possibility that lay before her, paths fraught with peril and uncertainty but also with adventure. Or she could choose to stay with a Jenkins family member until she had time to think, strategize, and utilize the resources that had sustained and comforted her and her child though the most tumultuous episode in American history. Either choice carried risks. Each also promised profound change within her family and community.

This was as true for her as it had been for those county slaves previously manumitted. There were instances of the manumission of slaves, but rarely were more than one or two slaves freed at the same time. And, not infrequently, those freed were older slaves. For those fortunate to acquire their freedom, the State of Virginia, beginning in 1806, required them to leave the state within 12 months or face re-enslavement. This law, and others that followed in 1816 and 1823, effectively acted as deterrents in cases of manumission within the state throughout the antebellum era. Former slaves—free blacks—who remained in the county were required at all times to carry the legal document granting their freedom and apply to the county court annually for permission to remain in the county.

The quest to remain in the county, or in close proximity, takes on added significance when we consider that Kentucky was a slave state and that Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois restricted or forbade free-black influx throughout the mid-1800s. In fact, in 1829, the Supreme Court of Ohio passed legislation requiring free blacks within the state to post a $500 bond within 30 days to remain in the state, a development that provoked 2,000 free blacks to petition the court to postpone implementation of the measure for three months. The following year, in Portsmouth, Ohio, a key station on the Underground Railroad located 45 miles upriver from Cabell County, local whites fed up with the pace of enforcement of the law forced approximately 80 blacks to leave the town. Though not uniformly enforced, these laws were invoked by white citizens when they felt justified or threatened, a development that could include harassment, violence, and/or expulsion of free blacks.

These developments (and others discussed herewith) help to reveal the peculiarities of the Ohio River valley and the contested nature of the borderland demarcated by the Ohio River during the era. The fact that Virginia ...