![]()

Part I

NOVEL PROLIFERATIONS

The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1974

![]()

1

COSTA BRAVA

This history is the history of possibility.

—MURIEL RUKEYSER, The Life of Poetry (1949)

Archives are notoriously unstable spaces (or deceptively stable ones), despite the appearance of stillness and order. They are built by fallible and invisible hands—librarians, family members, estate agents, patrons—who make all kinds of choices about aesthetics and politics, about what has value and what doesn’t, constructing a history out of those choices. Archives are never transparent, though we so often approach them as if they were made up of raw data. In the Muriel Rukeyser archive at the Library of Congress, time collapses. I was most interested in the period 1936–1939, the three years of the Spanish Civil War. Inside folders, inside boxes, wheeled out on squeaky dollies, I found photographs, journals, and lines of poetry written on napkins and the backs of receipts. I wasn’t sure what I was looking for, but there were things that I hoped to find. I was feeling a little breathless with anticipation. I was rummaging around among ghosts. I was looking for a lost revolution. I was following a love story. Rukeyser knew that everything that has been lost can be found again: every history can be remade, turned around, and rewritten. All dusty things can appear again in someone else’s poems, a century later in someone else’s hands. “Whatever can happen to anyone can happen to me,” she wrote.1 If those in power should fear one thing, it should be the greediness of the graduate student, the anarchy of the archive, the dedication of a child to his mother, the irregular heartbeat of historical movement. They should fear those “men and women / brave, setting up signals across vast distances,” calling to one another, saying: yes, there has been injustice, we fought for this and it happened like this, you are not alone—here is the poem, the novel, the picture that wraps and twines like DNA, connecting us into eternity.2

The previous fall I had begun graduate school and read Muriel Rukeyser for the first time. The Life of Poetry begins during her evacuation by boat from Barcelona in the first days of the Spanish Civil War. In the prologue to the book she writes of a profound and incendiary transformation, of how the passengers on the boat “spoke as if we were shadows on that deck, shadows cast backward by some future fire of explosion.”3 I’m not sure I understood or even realized the importance of that prologue until I read her second book of poems, published in 1938, which ends with an epic poem about “voyage and exile” through the Mediterranean, the figure of a man with “his Brueghel face” staring back at her from the dock, just a day before he will march to the Zaragoza front. He is a refrain, a call to action, his body a rhythmic and lyrical muse. In the next book of poems and the next, and then through the following decades until 1974, there are poems about the Spanish Civil War, unmarked graves scattered through her work, many of them about “this man, dock, war, a latent image.”4 Sometimes this is explicit, as in a book of poems dedicated to him, but more often he is obliquely rendered as a river, a song, the trace of a runner. Then there are the essays that have these same images and lines, published here and there over decades. Always they end with a moment of transformation and radicalization, when she learns “to say what she believes.” Always they speak “across time . . . as witness voice” to this man who is “the endless earth.”5

Muriel Rukeyser met Otto Boch on the train to Barcelona in July 1936. She was twenty-two and traveling to report on the People’s Olympiad, an alternative and a protest to Hitler’s Berlin Games. She was tall and had beautiful dark Jewish hair, which is the hair of literary heroines. She had already won the prestigious Yale Series of Younger Poets prize for her first book of poems, Theory of Flight (1935). A few years earlier, she had participated in publishing a radical and experimental literary magazine at Vassar College with Eleanor and Eunice Clark and Elizabeth Bishop, and then she dropped out of college and learned to fly a plane. She took a class on cultural anthropology at Columbia University in 1933 and became increasingly involved in racial justice movements, traveling to report on the Scottsboro Boys trial in Alabama, where she was jailed for “fraternizing” with African Americans. In early 1936 she traveled to West Virginia to document the Hawks Nest Tunnel mining disaster, an experience that she would transform into her most famous text, the modernist epic on capitalism, race, and environmental disaster, The Book of the Dead (1938). In the spring of 1936 she was asked to travel to London as an assistant for a couple, George and Betty Marshall, who were writing a book about cooperatives in England, Scandinavia, and Russia. It would be her first trip abroad. In London she met Bryher (Annie Winifred Ellerman), Robert Herring, T. S. Eliot, and C. Day Lewis. She went to a see Swan Lake with H.D., recording her nervousness about the meeting in her diary, writing, “She’ll hate all the flaws that show in my poems.”6 But H.D., the master precisionist, saw only good things in her work.7 After a month in London, Herring asked Rukeyser to fill in for a colleague and cover the antifascist games. She set off by train the next day.

Otto Boch was traveling to the games as a long-distance runner. A member of the Bavarian Red Front, he was forced out of Germany when Hitler came to power in 1933. He was leading an itinerant life in Italy and France, earning money as a cabinetmaker; it was a life emblematic of the migratory experience of so many during the interwar years, as governments fell, endemic violence rippling across borders. Boch had no identity card, no homeland. He did have a “Brueghel face.” In one picture of him, sent to Rukeyser from Zaragoza and placed at the center of her 1974 Esquire essay about the war, he looks out at the reader from under a knit hat, smiling. His cheekbones are high, like “carved wood,” she wrote. He looks handsome and kind. I understand why she fell in love. They spent only five days together, and then she was gone, and he was dead. Five days is enough.

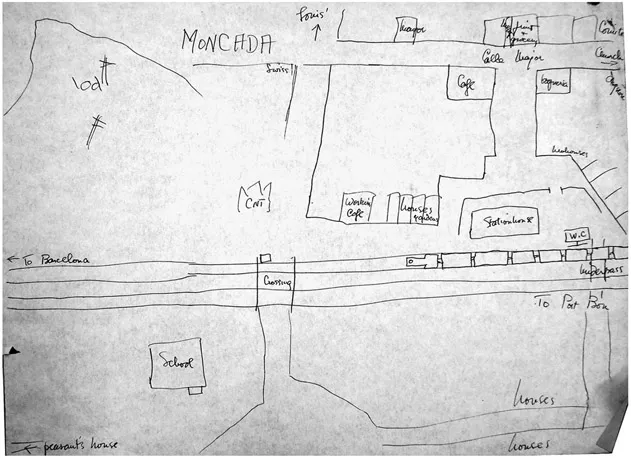

On my first trip to her archive, in box 1:4, I found three letters by Boch, sent from the front, written in German—“Dear Comrade Muriel!” he always begins. With them were an unpublished poem written on a torn-out sheet of notebook paper, titled “for O.B.,” her Esquire article ripped from the magazine, a tiny black journal from her trip to London and Spain, the ticket for her baggage, unused food vouchers for the People’s Olympiad that never happened, her eyewitness account of the first days of the war in the New York Herald Tribune, a hand-drawn map of the small town—Moncada (Montcada in Catalan)—where her train stopped as a general strike was called in support of the republic and war broke out, and an outline for a novel, but no novel.8

When I returned to the East Village with piles of photocopied material, I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how one understands the value of these kinds of things. In the tenement apartment where I lived on East Tenth Street, one that had been in my family since the 1960s, my aunt had found notes from the 1930s hidden behind the bricks in the wall. The notes felt important because they were secret, because they were connected to Jewish immigrant life echoing our own family’s history of diaspora—they represented the anonymous relationship that so many of us have to the multitude. Walter Benjamin alludes to how objects have an aura, how they give us access to ourselves in historical time, but they do more than that; they help us understand how power is constructed through material history, and how our ability to imagine and value lives lived can change our present. Saidiya Hartman writes, “Every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor.”9

Figure 2. A map Rukeyser drew of Montcada. Box 1:56, Muriel Rukeyser Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Rukeyser spent much of her life documenting the life of the multitude—the refugee, the migrant, the miner, the volunteer soldier fighting against fascism. In her writing on the Spanish Civil War, she imagined their lives intimately. Boch wasn’t anonymous, but he began to stand in for the many—names she encountered in a folder of refugees seeking aid, the images of thousands as they fled across the Pyrenees. For nearly fifty years she kept telling his story, returning to it, locating her poetry through it. Rukeyser also lived on Tenth Street, and in an archival fragment she writes:

From this night, which seems the end, I must make a beginning. I look up from the paper and my writing hand: through the tall side windows in the bay over Tenth Street. I see the people coming and going up and down. The Avenue lampposts are cold fluted black with the frozen soldiers on them, pillars twined in ritual green tied in ritual red. The letter telling me finally that he was killed years ago, and how, is behind the light in its own pool of the number 300. That is 300 men on a river in Spain, cut down in a battle foreknown by spies. Three charges on that day years ago in the spring on the Segre. The second one, after two hours of waiting, was forced back. Two hours later (and what was I doing downtown in this city, trying to remember for what I was asking punishment?). The order came to advance for the third time. O. took two machine guns and went ahead. They were cut down. 300 of them.

I love what I have always loved.

I believe in faith and resistance. The growing of all, the right to grow and the flowing order. The extending wish to which the images lead me.

The loss of our humanity is more depressing than the loss of life. But this you know, you have felt it many times.

Everyone rushing to surrender in his own way. If you will wait a moment. Now I will get ready, prepare in all the ways to go across country. I want my life as a woman; that is my life as a poet. It can only be lived by my growing enough life for me to reach the central motion of which the poems come—in that motion which seems to us stillness, since it is our own night location, the place where we speak to each other.10

Rukeyser kept this note to herself for decades, a few yellowing pages that she chose to include in the materials she donated to the New York Public Library when the archivist began to curate her collection on American literature. Rukeyser made sure this fragment was included.

Repetition in text signals to us what we are supposed to pay attention to, learn from, embody. It is the refrain of a Greek chorus, the end rhyme of a sonnet, an image renewed. Repetition in politics, in government, and in history shows us how systems of power deny and suppress the urgency of transformation. To break “the nightmare of repetition,” as Doris Lessing writes, is an imaginary and worldly pursuit.11 Rukeyser’s texts on Spain refract and interconnect, recurring and proliferating across her life, creating a history that encompasses, intertwines, and documents a changing twentieth century. “For our time,” she writes, “depends not on single points of knowledge, but on clusters and combinations.”12 The “moment of proof” she experienced in Spain is a call to action, something somatic, a personal history, and the story of the multitude; it is also a line that appears in a poem, a novel, an essay, a prologue, winding its way across literary time.13 Everything is in process, wavelike, in medias res.

On my second trip to the archive, I found a series of obituaries for Boch that Rukeyser had placed in German newspapers during the Munich Olympics in 1972. Of him she wrote, “Love’s not a trick of light.” When I touched the fine, fragile, yellowing newspaper clips that read, “In Remembrance of OTTO BOCH / Bavarian, runner, cabinet-maker, / fighter for a better world. / Any of his family and friends / wishing furt...