eBook - ePub

Engaging Evil

A Moral Anthropology

William C. Olsen, Thomas J. Csordas, William C. Olsen, Thomas J. Csordas

This is a test

- 322 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Engaging Evil

A Moral Anthropology

William C. Olsen, Thomas J. Csordas, William C. Olsen, Thomas J. Csordas

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Anthropologists have expressed wariness about the concept of evil even in discussions of morality and ethics, in part because the concept carries its own cultural baggage and theological implications in Euro-American societies. Addressing the problem of evil as a distinctly human phenomenon and a category of ethnographic analysis, this volume shows the usefulness of engaging evil as a descriptor of empirical reality where concepts such as violence, criminality, and hatred fall short of capturing the darkest side of human existence.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Engaging Evil un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Engaging Evil de William C. Olsen, Thomas J. Csordas, William C. Olsen, Thomas J. Csordas en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Philosophie y Éthique et philosophie morale. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

PART I

Chapter 1

FROM THEODICY TO HOMODICY

What should an anthropological theory of evil look like? First, it would have to recognize evil as both an analytical/etic and empirical/emic category relevant across cultures. That is, on the one hand, anthropologists would recognize evil as a concrete possibility in human relations, and on the other, ethnographers would document indigenous formulations of evil and lexical equivalents or approximations of words for “evil.” Second, such a theory would be based on existential considerations, with the understanding that in some instances, evil could constitute a generalized mode of being, recognized as more or less common in a society, and in others, evil could be a characteristic or quality of particular actions or series of actions. Third, an anthropological theory would have to confront the ambiguity in understanding evil’s locus and source as human or cosmological (supernatural or preternatural) and the manner in which this duality plays out in different societies and scenarios.

Finally, a theory of evil would require a minimal working definition that could survive comparison across modes of thinking and cultural contexts. The notion of malevolent destructiveness is the minimal definition that I prefer and propose. It is preferable, for example, to making evil a synonym of, and hence redundant with, violence, which is at least at first glance more easily identified empirically. Yet violence does not happen by itself—what matters is by whom and against whom it is committed. Moreover, if it is possible to refer to “violence in the most morally neutral sense of the term,” as Derrida does in discussing the human subjection of animals (2008, 25), then what other than evil would we name the criterion under which the moral neutrality of violence is abrogated? Insofar as it is even possible to articulate phrases such as “justifiable homicide” or a “just war,” it is evident that although all evil may be violent, not all violence is evil, and the problem of defining evil as such remains unaddressed (for valuable anthropological treatments of violence, see Das et al. 2000; Scheper-Hughes and Bourgois 2003).

Concern with evil is prompted in part by the current surge of interest in morality among anthropologists. If such an interest has not existed until now—and that is debatable—is it not pretentious to claim unselfconsciously that we are qualified at this moment to invent a moral anthropology? Such a move, if we are serious, means that we had better be prepared to confront and engage not only cultural relativism, which can be debated in a more or less theoretical and intellectually neutral manner, but also the far thornier issue of moral relativism. Cultural relativism is itself a moral stance that anthropologists like to think promotes tolerance; moral relativism is a challenge to the definition of morality that invites existential vertigo. The emerging anthropological models—moral anthropology, anthropology of morality, local moral worlds, anthropology of ethics (Csordas 2013)—presume actors who recognize moral challenges and want to make the morally best choice. They tend neither to theorize nor to address evil as such. Yet to elide the issue of evil is to dodge the question of morality; for in a sense, if it wasn’t for evil, morality would be moot, or at least there would be far less at stake. This is the case whether one understands evil as undermining morality from the outside or as intrinsic to morality in a foundational sense. Does evil exist; and if so, in what sense? Does it make a difference to distinguish ontological, cultural, discursive, or personal understandings of evil in relation to morality? Is it possible to be/do evil and not know it? Under what conditions can evil be perpetrated in the name of good or god?

Writing at the beginning of the twenty-first century, philosopher Amélie Rorty (2001) observed that contemporary ethics and moral philosophy had “taken the high road,” with philosophers formulating all kinds of moral ideals and discussion of moral evaluation while paying little attention to the “Dark Side.” In presenting a compendium of the Western canon of thought on evil, Rorty herself declines to refer to evil as a generic category while accepting it as an umbrella concept, invoking the image of a messy family genealogy reminiscent of Wittgenstein’s (1973) notion of family resemblance that recognizes multiple strands of commonality across different uses of a word without generic identity among the meanings of that word. A few pages later, she writes, “Evil may not be an ontological category or natural kind, but it seems a fundamental feature of human psychology that . . . we are revolted by actions that we classify as ‘abominable,’ ‘evil,’ ‘inhuman’” (2001, xv). In the meantime, since this cautious and somewhat ambivalent take on the status of evil, there appears to have been a resurgence of interest in evil among philosophers (Badiou 2001 [1998]; Bernstein 2002; Cole 2006; Dews 2008; Midgely 2001; Ricoeur 2007; Sheets-Johnstone 2008; Svendsen 2010), while the new wave of anthropological writing on morality continues on what Rorty called the high road.

When I began to consider this issue, my intent was in part to point out the relative silence of current anthropological literature on the topic of evil and pose the question of whether this silence is sustainable (Csordas 2013). Upon presenting my argument that a critical engagement with the concept of evil is requisite in a cross-culturally valid approach to morality before an audience of anthropologists and other social scientists, I was surprised that the response included considerable apprehension and even resistance. One colleague asserted that evil is a purely mythological concept that should stay that way, and that raising the question of evil is dangerous, like letting a genie out of a bottle. Another colleague claimed that evil is a metaphysical category, and that it is better to focus on material categories such as murder, genocide, torture, rape, and slavery. But as soon as one asks what these forms of abuse have in common, one is hard pressed to find a more precisely descriptive word than evil. In this respect, it is less productive to frame the question in terms of an opposition between evil as a metaphysical category and other more material categories than to recognize evil as a general category with specific instances, or at least a useful umbrella concept (Rorty 2001; Svendsen 2010). My point in recalling these objections is that, given their reflex skepticism as to whether a critically refined concept of evil is necessary to understanding morality, the desire to keep this genie in its bottle may be less a matter of intellectual prudence and more a failure of intellectual nerve. The failure of nerve in demurring to name evil as such is ironic insofar as anthropologists display plenty of courage in addressing specific instances of violence, depravity, and their consequent suffering. In sum, it is critical to examine the cultural constitution of ethical life and the social foundations of morality, but to continue acknowledging only the good does not go beyond good and evil, it only sidesteps a problem that anthropology, for the most part, finds disturbing.

Whence the readiness to dismiss evil as a mythological or metaphysical category rather than elaborating it as a moral or existential one? It is in part due to a sense that evil is a “Christian concept” and therefore necessarily ethnocentric. This element of the problem was expressed in an email exchange among contributors to the present volume when Gananath Obeyesekere wrote that “as far as I know there is no notion of EVIL in the Buddhist tradition and I am not sure how you can relate it to the more complex traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism. EVIL seems to me to be such a Christian turn.” Presentation of the word in all capital letters already presumes an objectified and essentialized evil, doubtless of little use anthropologically. Yet this comment raises a series of significant questions for how anthropology addresses evil. If Buddhism and Hinduism do not have an elaborated notion of evil, do they not have some formulations that bear a family resemblance to evil as malevolent destructiveness; and is it necessary that we find a notion similar to evil elaborated universally across religions in order for it to be useful? If evil is such a Christian turn, does this imply that evil is only relevant within Christianity and specifically in the way that Christianity elaborates it? Even more consequential from an anthropological standpoint, if Buddhism and Hinduism as religious systems do not elaborate evil, does this imply that evil cannot be perpetrated in Buddhist and Hindu societies? The Rohingya refugee crisis unfolded in a Buddhist society, Myanmar, whose government declared that people should not use the name “Rohingya”—do they also have the prerogative to abjure us from using the term evil in connection with this situation on the grounds that theirs is a Buddhist society? Finally, the comment refers specifically to religious systems. Does this imply that the anthropological study of morality cannot formulate a category of evil in human terms not beholden to religion? Wouldn’t that miss the opportunity to challenge the hegemony of that very Christian notion of evil to which Obeyesekere refers? In fact, given that evil or its cognates are broadly identifiable across cultures (evidenced in the contributions to the present volume), the anthropological reticence may stem less from a concern that evil is inherently Christian than from an uneasiness that, since the Christian concept of evil is hegemonic in Western civilization, our own analytic purview might be occluded by a lingering veil of Christian sensibility. The appropriate response, I suggest, is not to abjure the concept, but to insist that critical reflection be applied in deploying “evil” in a way that is not beholden to Christian presuppositions or the presuppositions of any other religious system. Indeed, Nietzsche (1967) argued that the very concept of evil originated as a product of class antagonism.

It would be naïve to think that overcoming this lingering hegemonic sensibility can be achieved with a snap of the fingers. In any case, to argue that evil be excluded from the study of morality on the grounds that it is necessarily mythological, metaphysical, or religious is to invoke a line of thinking applicable to morality itself. Nietzsche asserted, “‘Every evil the sight of which edifies a god is justified’: thus spoke the primitive logic of feeling—and was it, indeed, only primitive?” (1967, 69). He thus points to the facility with which evil can be transposed into goodness not only in the mythological primitive but the secularized modern mentality. Alain Badiou (in commenting on Levinas) claimed, “Every effort to turn ethics into the principle of thought and action is essentially religious” (2001, 223), thus suggesting that a foregrounding of morality and ethics such as that currently proposed in anthropology may already fall under the category of the religious, even prior to including within it a critical assessment of evil. It is in this context that we must face that there is within the existential structure of evil a challenge for anthropology parallel to the challenge for philosophy and theology identified by Ricouer, namely “the parallel demonization that makes suffering and sin the expression of the same baneful powers. It is never completely demythologized” (2007, 38). The structural duality of sin and suffering in itself affirms that an anthropology of morality must acknowledge at its very source the enigma of evil. This does not simply mean that an anthropological approach to morality must execute comparative, cross-cultural study. It also requires a specification of how an anthropological approach to morality itself defines evil as a demythologized human phenomenon. Is there a better dichotomy (or continuum) than good/evil, such as benevolent/malevolent or life-affirming/destructive? Would we be satisfied with a morally neutral “dangerous” instead of evil?

Given the challenge of defining evil as a demythologized human phenomenon, we can usefully recall David Parkin’s distinction among three senses in which we typically use the word evil: “the moral, referring to human culpability; the physical, by which is understood destructive elemental forces of nature, for example earthquakes, storms, or the plague; and the metaphysical, by which disorder in the cosmos or in relations with divinity results from a conflict of principles or wills” (1985, 15). These are all traditionally implicated in the problem of theodicy, but the first takes priority in a study such as ours. Moreover, when we refer to a human phenomenon, it is critical to take “phenomenon” in the specific sense of what appears in perception of self and other, relations and actions within the intersubjective lifeworld, and what comes to apperception in the process of meaning-making. As anthropologists concerned with meaning, we are not obligated to understand evil as a thing or substance (if it were, it would have to be as a noxious existential secretion), neither as a cosmological force or ontological element of the universe (whether personified or not). For Geertz, “the problem of meaning” was defined by “the existence of bafflement, pain, and moral paradox” (1973, 109). The problem of (or about) evil is the same sort of problem, closely related to but not the same as the problem of suffering and, in Geertz’s words, “concerned with threats to our ability to make sound moral judgments. What is involved in the problem of evil is not the adequacy of our symbolic resources to govern our affective life, but the adequacy of those resources to provide a workable set of ethical criteria, normative guides to govern our action” (1973, 106). In other words, evil is fundamentally implicated in morality and ethics, and all are bound up with meaning.

Insofar as meaning, morality, and evil are fundamentally human phenomena, and recognizing that neologism and barbarism are close kin in language, I want to say that, as anthropologists rather than theologians, our concern is not with theodicy but with homodicy. The difference between understanding evil as a cosmological force and a human phenomenon is vivid in a comparison between two famous literary doctors: Faust and Jekyll. The real-life model of Faust is said to have been a disreputable alchemist, what a more recent era would call a mad scientist. Parkin has observed: “Mephistopheles represented to Faust not just evil, but an experience that could not be obtained by either divine or secular means. The devil for, let us say, the reckless, brave, and foolish here offers a third world” (1985, 19). In this scenario, evil is a force external to humans, a cosmic force that, personified as the devil, has its own agenda, motives, and modus operandum. It can be negotiated within the sense of making a Faustian bargain, but it can also be prevailed against and even tricked so that the protagonist takes on a heroic cast as a representative of humanity independent of both god and the devil. Recall that though Marlowe’s Faust loses his soul, Goethe’s Faust is saved in the end. Even Marlowe’s doomed Faust has moral qualms and second thoughts throughout, maintaining some identity as a sympathetic, if tragic, figure.

Our other literary doctor is less ambiguous, a better example of evil as a purely human phenomenon. The mad scientist Dr. Jekyll was not compelled by the limits of knowledge and wisdom to seek a supernatural solution to his quest for enhanced pleasure and human fulfillment. For him, excess was transmuted into malevolence as he literally became addicted to evil. By the end, one has to suspect that the potion did not actually transform the mild and moral Dr. Jekyll, but in fact brought out Mr. Hyde as his true self—monstrous and evil. If an anthropological study of morality is addressed to the question of what it means to be human—synonymous with the question of defining human nature—this possibility of evil cannot be dodged. The likelihood that Jekyll did not initially realize that he was flirting with and then succumbing to evil enhances the tragedy and, for us, defines the conceptual ground upon which an anthropological approach to morality can be constructed.

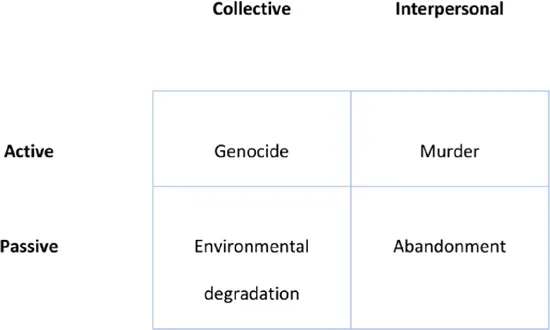

Let us take one more step toward defining this ground. Building on the minimal anthropological definition of evil as malevolent destructiveness that I proposed above, let us add an elementary structure to that destructiveness. The basic insight is that evil can have its locus at either a collective or interpersonal level, and that its mode of agency can be active or passive. These two dimensions generate an elementary structure as depicted in figure 1.1, with full acknowledgment of structuralism’s identification of the importance of binary opposition in human culture and consciousness. The distinction between collective and interpersonal is, in the first instance, a matter of scale, but it is also of consequence that evil perpetrated at the interpersonal level can more readily remain secret, darkness that remains in the dark. The distinction between active and passive in this instance is between hatred as onrushing annihilation and disregard as a careless turning away, where “careless” is understood as both without caution and without care. The two-by-two table generated by this elementary structure can be populated by ideal types of genocide as active collective evil, murder as active interpersonal evil, environmental degradation as passive collective evil, and abandonment as passive interpersonal evil.

Figure 1.1 Elementary structure of evil. Figure created by the author.

This formulation of an elementary structure is provisional, and certainly we could and would have to elaborate the contents of each of the cells. One pertinent question already evident is how to treat the passive evil of disregard, first of all with respect to whether evil resides in intention or in consequence. The example of environmental degradation is a consequence that can be described as evil, but the industrialists whose explicit intention is to maximize profits do not necessarily also have the intention of degrading the environment. Passively not knowing the results of one’s actions is not an excuse, but it is a problem for the theory of evil. Is not knowing the same as being unaware? Does the question of why one does not know come into play along with questions of denial, repression, and self-deception? Opening the door to such questions is as far as we can go here, and it comes with the anthropological fo...

Índice

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I

- PART II

- PART III

- Afterword

- Authors and Institutions

- Index

Estilos de citas para Engaging Evil

APA 6 Citation

Olsen, W., & Csordas, T. (2019). Engaging Evil (1st ed.). Berghahn Books. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2604208/engaging-evil-a-moral-anthropology-pdf (Original work published 2019)

Chicago Citation

Olsen, William, and Thomas Csordas. (2019) 2019. Engaging Evil. 1st ed. Berghahn Books. https://www.perlego.com/book/2604208/engaging-evil-a-moral-anthropology-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Olsen, W. and Csordas, T. (2019) Engaging Evil. 1st edn. Berghahn Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2604208/engaging-evil-a-moral-anthropology-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Olsen, William, and Thomas Csordas. Engaging Evil. 1st ed. Berghahn Books, 2019. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.